In the midst of all our plant medicinals studying, one very stressful pressure always comes up: It’s tough to get clinical trials of any promising candidate compound initiated anywhere in the world. But the class of compounds we study aren’t typical pharma drugs formulated straight from a laboratory drawing board; these are _plant _medicinals. So why not try to look for opportunities in the wild where people (or animals) are unwittingly already consuming candidate plant medicinals?

(image credit: Stefan Rodriguez | Unsplash)

Doing so would help satisfy a pharma product candidate’s safety criteria: Phase 1 trials. But Phase 2 and Phase 3 (whose purpose is to demonstrate efficacy for the targeted condition) are much harder to assess epidemiologically because COVID-19 has only been with us since December 2019; we just don’t have enough longitudinal data to work with to compare what people are eating and whether or not they recover expediently from infection . . .

Or do we…?

In order to jump to the head of the clinical trial line, we want to find 1) people who’ve been exposed to coronaviruses, and 2) find out what plants they might be consuming to manage it. To figure this out, we have one long and circuitous pathway ahead, so buckle up.

For starters, let’s keep in mind how similar that SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV (the one from SARS 2003) viruses are. They’re both coronaviruses (their genomes are 79% identical) — and they both evolved from lineages circulating in bats.

And yet coronaviruses aren’t new to the world — bats have been the reservoir not just for ten or twenty years, not even ten or twenty_ thousand_ years, but millions****of years. If only we knew which humans were repeatedly exposed to coronaviruses throughout history for our would-be longitudinal study.

To find where such a valuable group of humans can be found, we need to understand a little bit of virology, how virologists go about their work, and crucially, where their work takes them.

(image credit: Iakimchuk Iaroslav | Shutterstock.com)

The virologist’s tools of the trade

Virologists study the animal reservoirs of viruses that infect humans. Many viruses are zoonotic: they circulate in animal populations such as bats or birds, before making their way to humans. Often but necessarily always, the virus will evolve its way through an intermediary mammal along the way to human infectability. To study an animal reservoir, the virologists will go wherever any animals suspected of containing the virus live, like the caves of bats.

In caves suspected of harboring coronavirus, bat researchers capture groups of bats at a time. They perform fecal swabs to determine if a bat is infected. They do a PCR test on the samples, similar to tests we are subjected to for COVID-19 today. They then record the virus’ genome as it exists in the bats under study. Stay with me now, because this is where it gets interesting:

Virologists aren’t just looking for any single coronavirus. They are hunting for lineages of the _family of coronaviruses. They want to see how the virus varies — how it _mutates _— _from one bat cave to another. _Why is that important? _They want to see how close any of those coronaviruses are to being capable of hopping to humans.

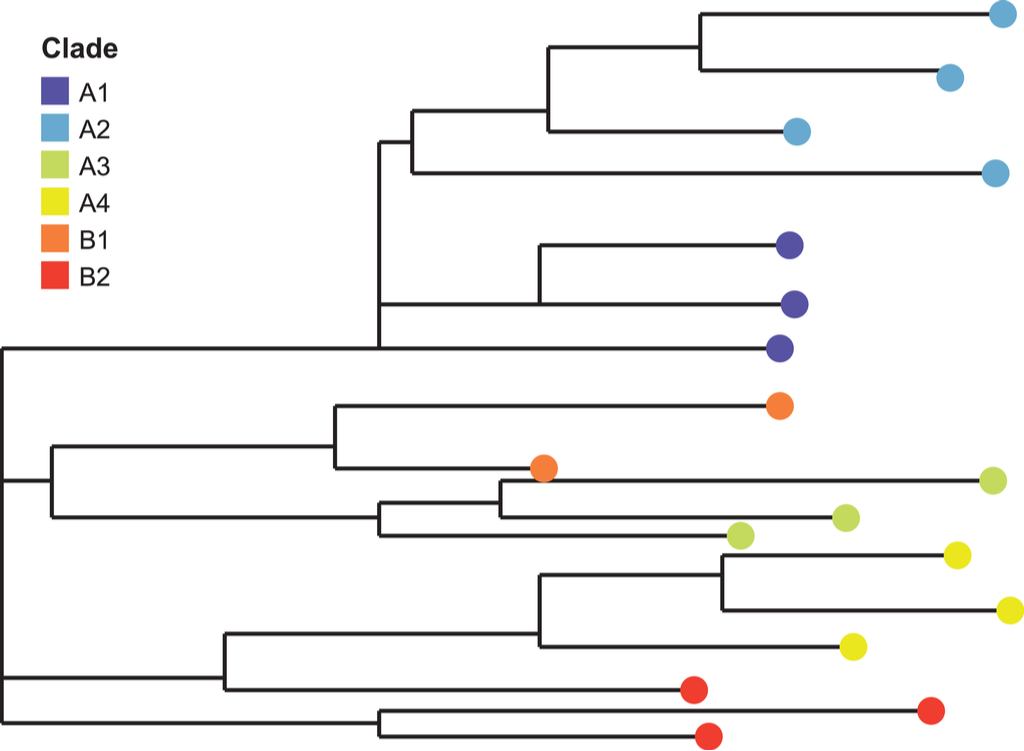

A phylogenetic tree (image credit: M. PATTHAWEE | Shutterstock.com)

To aid virologists in their virus-hunting field work, they employ a tool called a phylogenetic tree. A phylogenetic tree is like a family tree where they compile a listing of each unique version of a virus any researcher has ever encountered and whose genome’s been published. With a phylogenetic tree, the researchers can determine if they are looking at a branch lineage or a parent lineage of a particular viral clade. Virologists are particularly interested in finding a source of viral genetic diversity — one where many related viruses can be found in one place. Such a virally diverse source can indicate the current or historical presence of a parent lineage. It also increases the likelihood that they’ve found the source lineage, andcrucially the**geographic location**, of any virus clade known to have evolved its way to human infectability.

There might be a hundred different clades of coronavirus in circulation, but only a few that are capable of infecting human cells. In order to avoid the next pandemic, you want to know where the bats are that harbor the virus capable of infecting humans. To determine a particular clade’s human infectability, the researchers culture several million virions in a laboratory setting and see if they infect human cells in a test-tube.

#traditional-medicine #towards-data-science #plant-medicine #covid19 #data science