ES10 is still just a draft. But most features have already been implemented in Chrome, except Object.fromEntries, so why not start exploring it early? You’ll be ahead of the curve when all browsers start to support it. It’s only a matter of time. Here is a non-alien guide for anyone interested in exploring ES10.

ES10 is not as significant as ES6 in terms of new language features but it does add several interesting things (some of which will not yet work in your browser as of this time: 02/21/2019)

In ES6, arrow functions were hands down the most popular new feature.

What will it be in ES10?

BigInt — Arbitrary precision integers

BigInt is the 7th primitive type.

BigInt is an arbitrary-precision integer. What this means is that variables can now represent ²⁵³ numbers. And not just max out at 9007199254740992.

const b = 1n; // append n to create a BigInt

In the past, integer values greater than 9007199254740992 were not supported. If exceeded, the value would simply lock to MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 1:

const limit = Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER;

⇨ 9007199254740991

limit + 1;

⇨ 9007199254740992

limit + 2;

⇨ 9007199254740992 <--- MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 1 exceeded

const larger = 9007199254740991n;

⇨ 9007199254740991n

const integer = BigInt(9007199254740991); // initialize with number

⇨ 9007199254740991n

const same = BigInt("9007199254740991"); // initialize with "string"

⇨ 9007199254740991n

typeof

typeof 10;

⇨ 'number'

typeof 10n;

⇨ 'bigint'

Equality operators can be used between the two types:

10n === BigInt(10);

⇨ true

10n == 10;

⇨ true

Math operators only work within their own type:

200n / 10n

⇨ 20n

200n / 20

⇨ Uncaught TypeError:

Cannot mix BigInt and other types, use explicit conversions <

Leading — works, but + doesn’t:

-100n

⇨ -100n

+100n

⇨ Uncaught TypeError:

Cannot convert a BigInt value to a number

By the time you read this, matchAll will probably be officially implemented in Chrome C73 — if not, it’s still worth taking a look at. Especially if you’re a regular expression (regex) junkie.

string.prototype.matchAll()

If you run a Google search for JavaScript string match all, the first result will be something like: How do I write a regular expression to “match all”?

Top results will suggest using String.match with a regular expression and /g

…or RegExp.exec and/or RegExp.test with /g

First, let’s take a look at how the older spec worked.

String.match with string argument only returns the first match:

let string = “Hello”;

let matches = string.match(“l”);

console.log(matches[0]); // "l"

The result is a single **“l”** (Note: the match is stored in **matches[0]** not **matches**.)

Only **“l”** is returned from a search for **“l”** in the word**“hello”**.

The same goes for using string.match with a regex argument:

Let’s locate the **“l”** character in the string **“hello”** using the regular expression /l/:

let string = "Hello";

let matches = string.match(/l/);

console.log(matches[0]); // "l"

Add /g to the mix

But String.match with a regular expression and the /g flag does return multiple matches:

let string = "Hello";

let ret = string.match(/l/g); // (2) [“l”, “l”];

Great… we’ve got our multiple matches using < ES10.It worked all along.

So why bother with a completely new matchAll method? Well, before we can answer this question in more detail, let’s take a look at capture groups. If nothing else, you might learn something new about regular expressions.

Regular Expression Capture Groups

Capturing groups in regex is simply extracting a pattern from () parenthesis.

You can capture groups with /regex/.exec(string) and with string.match.

Regular capture group is created by wrapping a pattern in (pattern).

But to create **groups** property on resulting object it is: *(*?pattern).

To create a new group name, simply prepend ? inside brackets and in the result it the grouped (pattern) match will become groups.name attached to the match object**.** Here’s a practical example.

String specimen to match:

Here match.groups**.color** & match.groups**.bird** are created:

const string = 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull';

const regex = /(?<color>.*?)\*(?<bird>[a-z0-9]+)/g;

while (match = regex.exec(string))

{

let value = match[0];

let index = match.index;

let input = match.input;

console.log(`${value} at ${index} with '${input}'`);

console.log(match.groups.color);

console.log(match.groups.bird);

}

regex.exec method needs to be called multiple times to walk the entire set of the search results. During each iteration when .exec is called, the next result is revealed (it doesn’t return all matches right away.) Hence the while loop.

Console Output:

black*raven at 0 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

black

raven

lime*parrot at 11 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

lime

parrot

white*seagull at 23 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

white

seagull

But there is the quirk:

If you remove /g from this regex, you will create an infinite loop cycling on the first result forever. This has been a huge pain in the past. Imagine receiving a regex from some database where you are unsure of whether it has /g at the end or not. You’d have to check for it first, etc.

Now we have enough background to answer the question:

Good reasons to use .matchAll()

- It can be more elegant when using with capture groups. A capture group is simply the part of regular expression with ( ) that extracts a pattern.

- It returns an iterator instead of an array. Iterators on their own are useful.

- An iterator can be converted to an array using the spread operator (…)

- It avoids regular expressions with /g flag… useful when an unknown regular expression is retrieved from a database or outside source and used together with the archaic RegEx object.

- Regular expressions created using RegEx object cannot be chained using the dot (.) operator.

- Advanced: RegEx object changes internal**.lastIndex** property that tracks last matching position. This can wreck havoc in complex cases.

How does .matchAll() work?

The simple case

Let’s try to match all instances of letter **e** and **l** in the word **hello**. Because an iterator is returned we can walk it with a for…of loop:

// Match all occurrences of the letters: "e" or "l"

let iterator = "hello".matchAll(/[el]/);

for (const match of iterator)

console.log(match);

You can skip /g this time, it’s not required by the **.matchAll**method. Result:

[ 'e', index: 1, input: 'hello' ] // Iteration 1

[ 'l', index: 2, input: 'hello' ] // Iteration 2

[ 'l', index: 3, input: 'hello' ] // Iteration 3

Capture Groups example with .matchAll():

.matchAll has all of the benefits listed above. It’s an iterator, so we can walk it with for…of loop. And that’s the whole syntactic difference.

const string = 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull';

const regex = /(?<color>.*?)\*(?<bird>[a-z0-9]+)/;

for (const match of string.matchAll(regex)) {

let value = match[0];

let index = match.index;

let input = match.input;

console.log(`${value} at ${index} with '${input}'`);

console.log(match.groups.color);

console.log(match.groups.bird);

}

Note that /g flag is missing because it is already implied by .matchAll().

Console Output:

black*raven at 0 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

black

raven

lime*parrot at 11 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

lime

parrot

white*seagull at 23 with 'black*raven lime*parrot white*seagull'

white

seagull

Perhaps aesthetically it is very similar to the original regex.exec while loop implementation. But as stated earlier, this is the better way for many reasons mentioned above. And removing /g won’t cause an infinite loop.

Dynamic import

Imports can now be assigned to a variable:

element.addEventListener('click', async () => {

const module = await import(`./api-scripts/button-click.js`);

module.clickEvent();

});

Array.flat()

Flattening of a multi-dimensional array:

let multi = [1,2,3,[4,5,6,[7,8,9,[10,11,12]]]];

multi.flat(); // [1,2,3,4,5,6,Array(4)]

multi.flat().flat(); // [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,Array(3)]

multi.flat().flat().flat(); // [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]

multi.flat(Infinity); // [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]

Array.flatMap()

let array = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

array.map(x => [x, x * 2]);

Becomes:

[Array(2), Array(2), Array(2)]

0: (2)[1, 2]

1: (2)[2, 4]

2: (2)[3, 6]

Flatten the map again:

array.flatMap(v => [v, v * 2]);

[1, 2, 2, 4, 3, 6, 4, 8, 5, 10]

Object.fromEntries()

Transform a list of key & value pairs into an object:

let obj = { apple : 10, orange : 20, banana : 30 };

let entries = Object.entries(obj);

entries;

(3) [Array(2), Array(2), Array(2)]

0: (2) ["apple", 10]

1: (2) ["orange", 20]

2: (2) ["banana", 30]

let fromEntries = Object.fromEntries(entries);

{ apple: 10, orange: 20, banana: 30 }

String.trimStart() & String.trimEnd()

let greeting = " Space around ";

greeting.trimEnd(); // " Space around";

greeting.trimStart(); // "Space around ";

Well-formed JSON.stringify()

This update fixes processing of characters U+D800 through U+DFFF that sometimes can make their way into your JSON strings. It can be a problem because JSON.stringify may return these numbers formatted as values for which there are no equivalent UTF-8 characters. But JSON format requires UTF-8 encoding.

JSON object can be used to parse JSON format (but also more.) The JavaScript JSON object also has stringify and parse methods.

The parse method works with a well-formed JSON string, like:

'{ “prop1” : 1, "prop2" : 2 }'; // A well-formed JSON format string

Note that double quotes surrounding property names are absolutely required to create a string in correct JSON format. Absence of… or any other types of quotes will not produce a well-formed JSON.

'{ “prop1” : 1, "meth" : () => {}}'; // Not JSON format string

JSON string format is different from Object Literal… which looks almost the same but can use any type of quotes around property names and can also include methods (JSON format does not allow methods):

let object_literal = { property: 1, meth: () => {} };

Anyway, everything seems just fine. The first examples looks compliant. But they are also simple examples and most of the time will work without a hitch!

U+2028 and U+2029 Characters

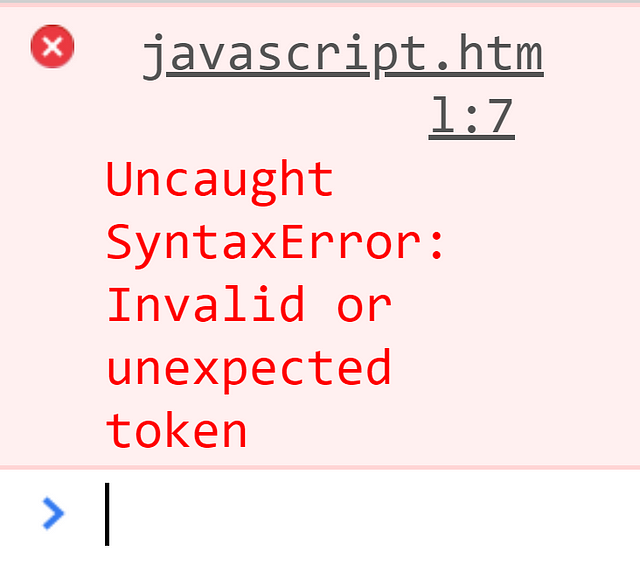

Here is the catch. EcmaScript prior to ES10 does not actually fully support JSON format. The unescaped line separator U+2028 and paragraph separator U+2029 characters are not accepted in pre-ES10 era:

The same is true for all characters between U+D800 — U+DFFF

If these characters crept into your JSON formatted string (let’s say from a database record) you might have ended up spending hours trying to figure out why the rest of your program generates parsing errors.

So if you pass eval a string like **“console.log(‘hello’)”** it will execute that JavaScript statement (by trying to convert the string to actual code.) This is also similar to how JSON.parse will process your JSON string.

Stable Array.prototype.sort()

The previous implementation of V8 used an unstable quick sort algorithm for arrays containing more than 10 items.

If you remove /g from this regex, you will create an infinite loop cycling on the first result forever. This has been a huge pain in the past. Imagine receiving a regex from some database where you are unsure of whether it has /g at the end or not. You’d have to check for it first, etc.

But this is no longer the case. ES10 offers a stable array sort:

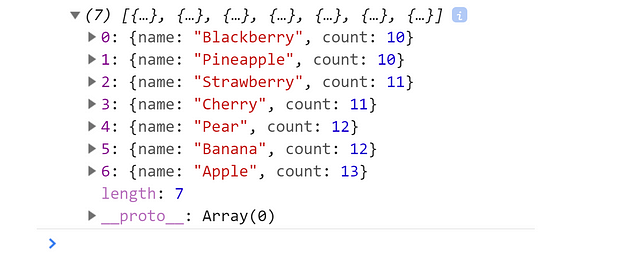

var fruit = [

{ name: "Apple", count: 13, },

{ name: "Pear", count: 12, },

{ name: "Banana", count: 12, },

{ name: "Strawberry", count: 11, },

{ name: "Cherry", count: 11, },

{ name: "Blackberry", count: 10, },

{ name: "Pineapple", count: 10, }

];

// Create our own sort criteria function:

let my_sort = (a, b) => a.count - b.count;

// Perform stable ES10 sort:

let sorted = fruit.sort(my_sort);

console.log(sorted);

Console Output (items appear in reverse order):

New Function.toString()

Functions are objects. And every object has a .toString() method because it originally exists on Object.prototype.toString(). All objects (including functions) are inherited from it via prototype-based class inheritance.

This means we’ve already had funcion.toString() method before.

But ES10 further tries to standardize string representation of all objects and built-in functions. Here is the big picture with samples for various new cases:

Classic example:

function () { console.log('Hello there.'); }.toString();

Console Output (body of the function in string format:)

⇨ function () { console.log('Hello there.'); }

And here are the rest of the cases:

Directly from function name:

Number.parseInt.toString();

⇨ function parseInt() { [native code] }

With bound context:

function () { }.bind(0).toString();

⇨ function () { [native code] }

Built-in callable function object:

Symbol.toString();

⇨ function Symbol() { [native code] }

Dynamically-generated function:

Function().toString();

⇨ function anonymous() {}

Dynamically-generated generator function*:

function* () { }.toString();

⇨ function* () { }

prototype.toString

Function.prototype.toString.call({});

⇨ Function.prototype.toString requires that 'this' be a Function"

Just standardized across many more different situations.

Optional Catch Binding

In the past, a catch clause in a try / catch statement required a variable.

The try / catch statement helps us intercept errors on the terminal level:

Here’s a refresher.

try {

// Call a non-existing function undefined_Function

undefined_Function("I'm trying");

}

catch(error) {

// Display the error if statements inside try above fail

console.log( error ); // undefined_Function is undefined

}

But in some cases, the required error variable was left unused:

try {

JSON.parse(text); // <--- this will fail with "text not defined"

return true; <--- exit without error even if there is one

}

catch (redundant_sometmes) <--- this makes error variable redundant

{

return false;

}

Whoever wrote this code exits from the try clause by trying to forcing true. But… this isn’t actually what happens (as pointed out by Douglas Massolari.)

(() => {

try {

JSON.parse(text)

return true

} catch(err) {

return false

}

})()

=> false

In ES10 Catch Error Binding Is Optional

You can now skip error variable:

try {

JSON.parse(text);

return true;

}

catch

{

return false;

}

There is currently no way to test what the try statement evaluates to like in the previous example. But once it comes out I’ll update this part.

Standardized globalThis object

The global this was not standardized before ES10.

In production code you would “standardize” it across multiple platforms on your own by writing this monstrosity:

var getGlobal = function () {

if (typeof self !== 'undefined') { return self; }

if (typeof window !== 'undefined') { return window; }

if (typeof global !== 'undefined') { return global; }

throw new Error('unable to locate global object');

};

But even this didn’t always work. So ES10 added the globalThis object which should be used from now on to access global scope on any platform:

// Access global array constructor

globalThis.Array(0, 1, 2);

⇨ [0, 1, 2]

// Similar to window.v = { flag: true } in <= ES5

globalThis.v = { flag: true };

console.log(globalThis.v);

⇨ { flag: true }

Symbol.description

**description** is a read-only property that returns optional description of **Symbol** objects.

let mySymbol = 'My Symbol';

let symObj = Symbol(mySymbol);

symObj; // Symbol(My Symbol)

String(symObj) === 'Symbol(${mySymbol})`); // true

symObj.description; // "My Symbol"

Hashbang Grammar

AKA the shebang unix users will be familiar with.

It specifies an interpreter (what will execute your JavaScript file?).

ES10 standardizes this. I won’t go into details on this because this is technically not really a language feature. But it basically unifies how JavaScript is executed on the server-side end.

$ ./index.js

Instead of:

$ node index.js

If you remove /g from this regex, you will create an infinite loop cycling on the first result forever. This has been a huge pain in the past. Imagine receiving a regex from some database where you are unsure of whether it has /g at the end or not. You’d have to check for it first, etc.### ES10 Classes: private, static & public members

New syntax character # octothorpe (hash tag) is now used to define variables, functions, getters and setters directly inside the class body’s scope… alongside the constructor and class methods.

Here is a rather meaningless example that focuses only on new syntax:

class Raven extends Bird {

#state = { eggs: 10};

// getter

get #eggs() {

return state.eggs;

}

// setter

set #eggs(value) {

this.#state.eggs = value;

}

#lay() {

this.#eggs++;

}

constructor() {

super();

this.#lay.bind(this);

}

#render() {

/* paint UI */

}

}

To be honest I think it makes the language a bit harder to read.

It is still my favorite new feature because I love classes from C++ days.

Conclusion & Feedback

ES10 is a new set of features that hasn’t had the chance to be fully explored in a production environment yet. Let me know if you have any corrections, suggestions or any other feedback.

Often times I write a tutorial because I want to learn some of the subjects myself. This was one of those times. But not without the help of other resources already compiled by others:

Thanks to Sergey Podgornyy who wrote this ES10 tutorial.

And Selvaganesh who wrote this ES10 tutorial.

Originally published by JavaScript Teacher at freecodecamp.org

#javascript