The Jupyter Notebook with the code for this post can be found here, and the original post, here.

How do cities grow?

Whether large cities are just scaled-up versions of small cities is still an open question. An important one for that matter. In order to plan better cities, we need an improved understanding of how geography, urban economy, social and physical networks and political institutions come together to bring about growth or decline of cities. To achieve this, a thorough outlook on how urban settlements evolved over time is required. Substantial research claims that the social, economic, political, and organizational structures and their innovations that would triumph in “modernity,” “capitalism,” and the Industrial Revolution are rooted in and developed from medieval European settlements. On the other hand, medieval cities were qualitatively different: much smaller, agrarian, with a lower productivity, simpler technologies, and no organized market economy. Strictly hierarchical institutions as the feudal government, Church, and guilds exerted a much stronger influence on the organization of social and economic life in medieval cities compared to analogous structures in modern cities. This influence manifested itself in segregated, corporate societies in which social groupings limited social and economic interactions and opportunities for individuals and families. The modern Western “free flow” of ideas, people, and goods was alien to medieval cities.

These two different and at first sight conflicting perspectives raise the empirical question: Were medieval cities fundamentally different from modern cities? Or is there a continuum of urban processes, form and function from medieval to modern cities?

Far from being just an interesting question, asking such questions is important for building a broad, historically-informed theory of urbanization. In this post, we will narrow down the raised questions and will try to find out whether hierarchical institutions such as the Church or guilds limited and constrained social mixing and interaction in cities affecting urban economic and spatial growth. We will look at a dataset of built-up area and resident populations of 173 medieval cities at ca. 1300 AD, uncover their relationship with simple statistical techniques, and interpret the results in relation to two models from settlement scaling theory. The first model, originally developed for describing modern cities, constructs the built-up area of cities as a function of their population size, considering the city as an unconstrained non-hierarchical socio-economic network embedded in space. The second model builds on top of the first model by adding restrictions to social and economic interactions due to the impact of medieval institutions on social networking. This latter model predicts that, if this restrictive impact is strong, cities will have weak agglomeration effects, which would be visible in the relationship between built-up area and population.

Spatial and social organisation models in cities

On the one hand, one can imagine a medieval city as a self-organized, non-hierarchical social and spatial network entity. If so, interactions among people are only limited by transaction, transportation, opportunity costs, and the so-called “matching costs” of between the needs, skills, and resources of individuals. In such a network, interactions between any two persons are not restricted and occur freely. We will call this view of cities the social reactor model. However, as already mentioned, such hierarchically organized medieval institutions as the Church, feudal authorities, guilds, family ties, etc., exerted huge power and control in medieval cities. This forms the basis for the hypothesis that these institutions strongly regulated the contacts between people in different social groups, hence restricting the social interactions that boost economic productivity, flows of ideas, and the creation of knowledge and innovation. We shall call this view of cities the structured social interaction model and discuss the corresponding mathematical model based on hierarchical graphs capturing the mentioned social and economic regulation. We will then statistically analyse the available data and test our hypothesis by interpreting the results of the data analysis from the perspective of these models.

The Social Reactor Model

The fundamental idea behind most urban socioeconomic theories, including classical models of geography and urban planning, is the concept of a “spatial equilibrium”. In its simplest form formulated by William Alonso, it states that within a city, individuals and firms choose their location by drawing a balance between land rents and transportation costs and economic preferences, given the available resources. This typically leads to a monocentric spatial organisation with the highest land prices at the city core — the most favourable location in terms of accessibility and low transportation costs — decreasing as one moves away from the city center. Urban or settlement scaling theory, on the other hand, has the same basic elements as the Alonso model, except that it offers a more refined modelling framework relating the microprocesses and physical structures in cities to their population through a scaling exponent, as described in what follows. The core idea behind settlement scaling theory is that all human settlements — irrespective of scale or socio-economic complexity — share essential quantitative similarities in terms of general form and function. This comes from the multilayered gains from social agglomeration, whether for economic specialization, innovation, shared infrastructure, common pool of workforce, defence, religion, or trade. In their essence, they model the relationship between various socio-economic characteristics of a city to its population. A key difference between urban economics models and urban scaling theory is the replacement of production or utility functions common in economics with a socio-economic network of interactions.

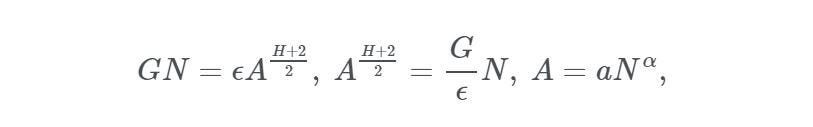

That said, let’s derive the expected relationship between the population of a city, N, and its built-up area, A. Unlike classical urban economic models, we do not have to assume a radial monocentric city structure. To do this, we balance the average benefit to an individual from social-economic interactions against the associated transportation costs:

In the equation, G is the net benefit per interaction times the area an individual covers over time. Given the differences in social relationships, economic productivity, and innovation in medieval vs. modern cities, _G _can vary significantly across time. ϵ is the cost of movement per unit length, which is a function of technology (walking, horse riding, etc.). H, another ingredient in specifying the cost associated to individual interactions in a city, is a fractal dimension characterising how people explore a city. For H=1, individuals move in the city through line-like trajectories, while for H→2, they explore the city as an area, exhaustively. In the opposite limit of H→0, individuals remain constrained to a single place (the trajectory is a static point), and the city effectively ceases to be a socio-economic network of interactions. With some simple high school algebra tweaking, we obtain:

where α:=2/(H+2) and a:=(G/ϵ)^α. This simple result describes some of the most important properties of urban settlements. First, if benefits from social interactions are small relative to transportation costs, which was the case in medieval cities, then the prefactor, a, will be small and the city will be quite dense. Note also that if H=0, as could have happened in a segregated settlement, the total built-up area, A, becomes proportional to population, with no agglomeration effects whatsoever. For H=1, one obtains the special exponent value, α=2/3, a situation described as the amorphous settlement model, because it neglects any spatial structure and organisation in cities. In such settlements, population density, n, increases rapidly with population size as n(N) = N/A(N) = a^(−1) N^(1/3).

However, so far, we have not yet considered the fact that urban settlements are not organised as blank isotropic canvases, but become organised by locations of interest and the networks making the access to them possible (streets, canals, paths). This means that the effective space for social-economic interactions in cities is defined by its access network. The total network area,_ A_n_, can be derived from population density N/A:

A_n(N) ∼ N_d=A^(1/2) N^(1/2) where _d _is the average distance between individuals d=(A/N)^(1/2). Further,

where δ = H/2(H+2) and a_0=la^(1/2). Here l is a length scale capturing the width of the network at each location of interest (e.g., doors and entrance-ways). For H=1, we obtain an exponent of 1−δ = 5/6.

#data-analysis #cities #data-science #statistics #python #data analysis