The 5 Most Common Mistakes That Python Developers Make

With lots of practice, programming will get gradually get easier, but the bottom line is that

programming is hard.

It can be made even more difficult with an unfortunate combination of assumption and working problems out on your own. Without a mentor especially, it can be rather difficult to ever even know if one way you are doing something is wrong. We are certainly all guilty of going into our code at a later date and refactoring because we are all learning constantly how to do things in a better way. Fortunately, with the right amount of awareness, correcting these mistakes can make you a significantly better programmer.

The greatest way to become a greater programmer is to overcome mistakes and problems. There is always a better way of doing something, it’s finding that specific better way that is challenging. It’s easy to get used to doing one thing or another, but sometimes a bit of a shake-up is needed to really get the ball rolling on becoming a great engineer.

Not Implemented

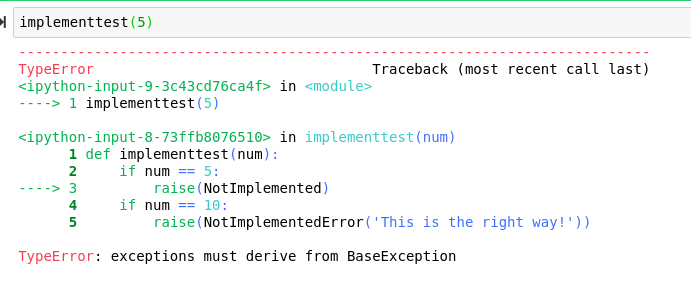

Though the “ Not Implemented” error is likely one of the least common errors on this list, I think it’s important to issue a reminder. Raising NotImplemented in Python will not raise a NotImplemented error, but instead will raise a Type error. Here is a function I wrote to illustrate this:

def implementtest(num):

if num == 5:

raise(NotImplemented)

Whenever we try to run the function where “ num” is equal to 5, watch what happens:

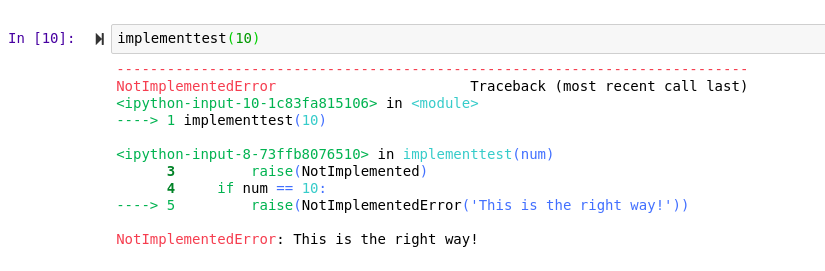

The solution to raising the correct exception is to raise the NotImplementedError rather than raising NotImplemented. To do this, I modified our function:

def implementtest(num):

if num == 5:

raise(NotImplemented)

if num == 10:

raise(NotImplementedError('This is the right way!'))

And running this will give us the proper output:

Mutable Defaults

(This one I was guilty of)

Default arguments in Python are evaluated once, and the evaluation takes place whenthe function definition is executed. Given that these arguments are evaluated once, each element inbound is used in each call, which means that the data contained in the variable is mutable across each time it is accessed within the function.

def add(item, items=[]):

items.append(item)

What we should do instead is set the value of our parameter to nothing, and add a conditional to modify the list if it doesn’t exist

def add(item, items=None):

if items is None:

items = []

items.append(item)

Though this mostly applies to the statistical/DS/ML side of Python users, having immutable data is universally important depending on the circumstances.

Global Variables

Inside of an object-oriented programming language, global variables should be kept to a minimum. However, I think it is important to subtitle that claim by explaining that global variables are certainly necessary, and quite alright in some situations. A great example of this is Data Science, where this is a limited amount of object-oriented programming actually going on, and Python is being used more functionally than it typically would.

Global variables can cause issues with naming, and privacy while multiple functions are calling on and relying on the same value. A great example of a global variable I would say is okay to do is something like a file-path, especially one that is meant to be packaged along with your Python file. Even in writing a Gtk class and moving a graphical user interface builder should be done privately, rather than globally.

Copy!

Using copy can be objectively better than using normal assignment. Normal assignment operations will simply point the new variable towards the existing object, rather than creating a new object.

d = 5

h = d

There are two main types of copies that can be performed with the copy module for Python,

shallow copy and deep copy.

The difference between these two types of copies comes down to the type of variable you want to pass through the function. When using deep copying on variables that are contained within a single byte of data like integers, floats, and booleans or strings, the difference between a shallow copy and a deep copy cannot be felt. However, when working with lists, tuples, and dictionaries I would recommend always deep copying.

A shallow copy constructs a new compound object and then (to the extent possible) inserts references into it to the objects found in the original. A deep copy constructs a new compound object and then, recursively, inserts copies into it of the objects found in the original. Given those definitions, it’s easy to see why you might want to use one or the other for a given datatype.

import copy

l = [10,15,20]

h = 5

hcopy = copy.copy(h)

z = copy.deepcopy(l)

In order to test our results, we can simply check if their variable id is the same with a conditional statement:

print id(h) == id(hcopy)

False

Conclusion

Being a great programmer is about constantly improving, and hopefully, some misconceptions can be cleared up over time. It’s a gradual and painful process, but with lots of practice and even more information, following simple guidelines and advice like this can certainly be rewarding. Sharing “ not-to-dos” like this generally make great conversation and makes everyone involved a great programmer, so I think discussing this can certainly be beneficial regardless of how far along you are on your endless programming journey.

#python #programming