Can You do Object Oriented Programming in JavaScript

JavaScript is not a class-based object-oriented language, but it still has a way of implementing it. We’ll look at OOP in JavaScript in this article.

According to Wikipedia, class-based programming is

a style of Object-oriented programming (OOP) in which inheritance occurs via defining classes of objects, instead of inheritance occurring via the objects alone

The most developed and popular model of OOP is class-based.

JavaScript is a prototype-based langauge. According to the MDN Docs,

A prototype-based language has the notion of a prototypical object, an object used as a template from which to get the initial properties for a new object.

Examine the following code:

let names = {

fname: "Dillion",

lname: "Megida"

}

console.log(names.fname);

console.log(names.hasOwnProperty("mname"));

// Expected Output

// Dillion

// false

The object variable names has only two properties - fname and lname . No methods at all. So where does hasOwnProperty come from?

Well, it comes from the Object prototype.

Try logging the contents of the variable to the console:

console.log(names);

When you expand the results in the console, you’ll get this:

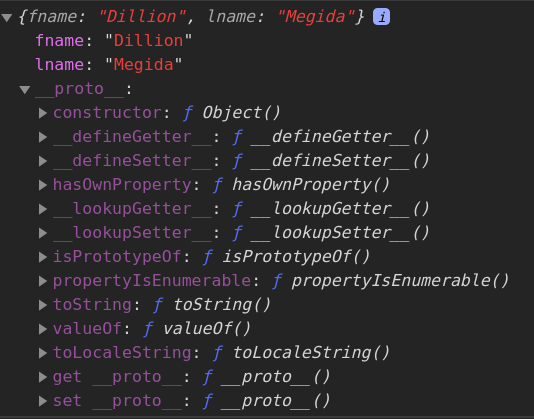

Notice the last property - __proto__? Try expanding it:

You’ll see a set of properties under the Object constructor. All these properties are coming from the global Object prototype. If you look closely, you’ll also notice our hidden hasOwnProperty .

In other words, all objects have access to the Object’s prototype. They do not possess these properties, but are granted access to the properties in the prototype.

The __proto__ property

This points to the object which is used as a prototype.

This is the property on every object that gives it access to the Object prototype property.

Every object has this property by default, which refers to the Object Protoype except when configured otherwise (that is, when the object’s __proto__ is pointed to another prototype).

Modifying the __proto__ property

This property can be modified by explicitly stating that it should refer to another prototype. The following methods are used to achieve this:

Object.create()

function DogObject(name, age) {

let dog = Object.create(constructorObject);

dog.name = name;

dog.age = age;

return dog;

}

let constructorObject = {

speak: function(){

return "I am a dog"

}

}

let bingo = DogObject("Bingo", 54);

console.log(bingo);

In the console, this is what you’d have:

Notice the __proto__ property and the speak method?

Object.create uses the argument passed to it to become the prototype.

new keyword

function DogObject(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

DogObject.prototype.speak = function() {

return "I am a dog";

}

let john = new DogObject("John", 45);

john’s __proto__ property is directed to DogObject’s prototype. But remember, DogObject’s prototype is an object (key and value pair), hence it also has a __proto__ property which refers to the global Object protoype.

This technique is referred to as PROTOTYPE CHAINING.

Note that: the new keyword approach does the same thing as Object.create() but only makes it easier as it does some things automatically for you.

And so…

Every object in Javascript has access to the Object’s prototype by default. If configured to use another prototype, say prototype2, then prototype2 would also have access to the Object’s prototype by default, and so on.

Object + Function Combination

You are probably confused by the fact that DogObject is a function (function DogObject(){}) and it has properties accessed with a dot notation. This is referred to as a function object combination.

When functions are declared, by default they are given a lot of properties attached to it. Remember that functions are also objects in JavaScript data types.

Now, Class

JavaScript introduced the class keyword in ECMAScript 2015. It makes JavaScript seem like an OOP language. But it is just syntatic sugar over the existing prototyping technique. It continues its prototyping in the background but makes the outer body look like OOP. We’ll now look at how that’s possible.

The following example is a general usage of a class in JavaScript:

class Animals {

constructor(name, specie) {

this.name = name;

this.specie = specie;

}

sing() {

return `${this.name} can sing`;

}

dance() {

return `${this.name} can dance`;

}

}

let bingo = new Animals("Bingo", "Hairy");

console.log(bingo);

This is the result in the console:

The __proto__ references the Animals prototype (which in turn references the Object prototype).

From this, we can see that the constructor defines the major features while everything outside the constructor (sing() and dance()) are the bonus features (prototypes).

In the background, using the new keyword approach, the above translates to:

function Animals(name, specie) {

this.name = name;

this.specie = specie;

}

Animals.prototype.sing = function(){

return `${this.name} can sing`;

}

Animals.prototype.dance = function() {

return `${this.name} can dance`;

}

let Bingo = new Animals("Bingo", "Hairy");

Subclassing

This is a feature in OOP where a class inherits features from a parent class but possesses extra features which the parent doesn’t.

The idea here is, for example, say you want to create a cats class. Instead of creating the class from scratch - stating the name, age and species property afresh, you’d inherit those properties from the parent animals class.

This cats class can then have extra properties like color of whiskers.

Let’s see how subclasses are done with class.

Here, we need a parent which the subclass inherits from. Examine the following code:

class Animals {

constructor(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

sing() {

return `${this.name} can sing`;

}

dance() {

return `${this.name} can dance`;

}

}

class Cats extends Animals {

constructor(name, age, whiskerColor) {

super(name, age);

this.whiskerColor = whiskerColor;

}

whiskers() {

return `I have ${this.whiskerColor} whiskers`;

}

}

let clara = new Cats("Clara", 33, "indigo");

With the above, we get the following outputs:

console.log(clara.sing());

console.log(clara.whiskers());

// Expected Output

// "Clara can sing"

// "I have indigo whiskers"

When you log the contents of clara out in the console, we have:

You’ll notice that clara has a __proto__ property which references the constructor Cats and gets access to the whiskers() method. This __proto__ property also has a __proto__ property which references the constructor Animals thereby getting access to sing() and dance(). name and age are properties that exist on every object created from this.

Using the Object.create method approach, the above translates to:

function Animals(name, age) {

let newAnimal = Object.create(animalConstructor);

newAnimal.name = name;

newAnimal.age = age;

return newAnimal;

}

let animalConstructor = {

sing: function() {

return `${this.name} can sing`;

},

dance: function() {

return `${this.name} can dance`;

}

}

function Cats(name, age, whiskerColor) {

let newCat = Animals(name, age);

Object.setPrototypeOf(newCat, catConstructor);

newCat.whiskerColor = whiskerColor;

return newCat;

}

let catConstructor = {

whiskers() {

return `I have ${this.whiskerColor} whiskers`;

}

}

Object.setPrototypeOf(catConstructor, animalConstructor);

const clara = Cats("Clara", 33, "purple");

clara.sing();

clara.whiskers();

// Expected Output

// "Clara can sing"

// "I have purple whiskers"

Object.setPrototypeOf is a method which takes in two arguments - the object (first argument) and the desired prototype (second argument).

From the above, the Animals function returns an object with the animalConstructor as prototype. The Cats function returns an object with catConstructor as it’s prototype. catConstructor on the other hand, is given a prototype of animalConstructor.

Therefore, ordinary animals only have access to the animalConstructor but cats have access to the catConstructor and the animalConstructor.

#javascript #web-development #oop