A tutorial on linear regression typically starts with some dependent variable “y” and one independent variable “x”. This is usually followed by an **OLS **(Ordinary Least Squares) deduction to find the (clichéd) line of best fit.

But hold on. Why do we start with one independent variable “x”? What if we have only “y” and no other information? Let’s find out, and in the process we would hopefully discover the things we already know as facts.

Let’s take a **contrived **example of 6 independent and untrained hobbyists who set out to find the number of Coronavirus a person needs to inhale to be infected with the dreaded Covid-19.

Here is the unscientific data-set they come up with: {7, 3, 9, 1, 6, 4}. However, we need to report only one number to WHO to help them find a cure. Let’s call it m.

We don’t know what m is, but we do know OLS (Ordinary Least Squares). To put it a little more mathematically: We need to find m such that this **_cost _**is minimized:

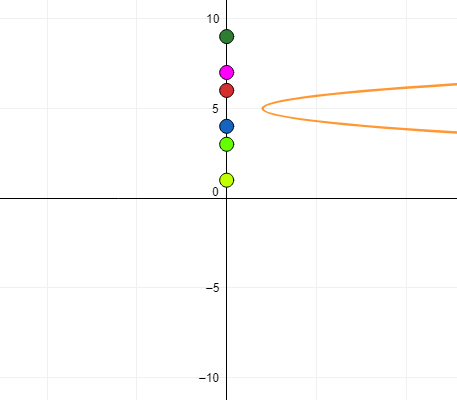

(7-m)² + (3-m)² + (9-m)² + (1-m)² + (6-m)² + (4-m)²

Let’s plot this on a chart and see what it looks like. We are looking at that beautiful orange curve which clearly has the lowest value at m=5.

It’s easy enough to set the derivative of the _cost _with respect to m to zero and arrive at the same conclusion i.e. dcost/d**_m **= _0. I would leave the derivation to you, but if you follow through, here is where we finally arrive.

#mean #ordinary-least-square #machine-learning #linear-regression #statistics #deep learning