I wrote this article to help you quickly learn CSS and get familiar with the advanced CSS topics.

CSS is often quickly dismissed as an easy thing to learn by developers, or one thing you just pick up when you need to quickly style a page or app. Due to this reason, it’s often learned on-the-fly, or we learn things in isolation right when we have to use them. This can be a huge source of frustration when we find that the tool does not simply do what we want.

This article will help you get up to speed with CSS and get an overview of the main modern features you can use to style your pages and apps.

I hope to help you get comfortable with CSS and get you quickly up to speed with using this awesome tool that lets you create stunning designs on the Web.

Click here to get a PDF / ePub / Mobi version of this post to read offline

CSS, a shorthand for Cascading Style Sheets, is one of the main building blocks of the Web. Its history goes back to the 90’s, and along with HTML it has changed a lot since its humble beginnings.

As I’ve been creating websites since before CSS existed, I have seen its evolution.

CSS is an amazing tool, and in the last few years it has grown a lot, introducing many fantastic features like CSS Grid, Flexbox and CSS Custom Properties.

This handbook is aimed at a vast audience.

First, the beginner. I explain CSS from zero in a succinct but comprehensive way, so you can use this book to learn CSS from the basics.

Then, the professional. CSS is often considered like a secondary thing to learn, especially by JavaScript developers. They know CSS is not a real programming language, they are programmers and therefore they should not bother learning CSS the right way. I wrote this book for you, too.

Next, the person that knows CSS from a few years but hasn’t had the opportunity to learn the new things in it. We’ll talk extensively about the new features of CSS, the ones that are going to build the web of the next decade.

CSS has improved a lot in the past few years and it’s evolving fast.

Even if you don’t write CSS for a living, knowing how CSS works can help save you some headaches when you need to understand it from time to time, for example while tweaking a web page.

Thank you for getting this ebook. My goal with it is to give you a quick yet comprehensive overview of CSS.

Flavio

You can reach me via email at flavio@flaviocopes.com, on Twitter @flaviocopes.

My website is flaviocopes.com.

Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION TO CSS

- A BRIEF HISTORY OF CSS

- ADDING CSS TO AN HTML PAGE

- SELECTORS

- CASCADE

- SPECIFICITY

- INHERITANCE

- IMPORT

- ATTRIBUTE SELECTORS

- PSEUDO-CLASSES

- PSEUDO-ELEMENTS

- COLORS

- UNITS

- URL

- CALC

- BACKGROUNDS

- COMMENTS

- CUSTOM PROPERTIES

- FONTS

- TYPOGRAPHY

- BOX MODEL

- BORDER

- PADDING

- MARGIN

- BOX SIZING

- DISPLAY

- POSITIONING

- FLOATING AND CLEARING

- Z-INDEX

- CSS GRID

- FLEXBOX

- TABLES

- CENTERING

- LISTS

- MEDIA QUERIES AND RESPONSIVE DESIGN

- FEATURE QUERIES

- FILTERS

- TRANSFORMS

- TRANSITIONS

- ANIMATIONS

- NORMALIZING CSS

- ERROR HANDLING

- VENDOR PREFIXES

- CSS FOR PRINT

- WRAPPING UP

INTRODUCTION TO CSS

CSS (an abbreviation of Cascading Style Sheets) is the language that we use to style an HTML file, and tell the browser how should it render the elements on the page.

In this book I talk exclusively about styling HTML documents, although CSS can be used to style other things too.

A CSS file contains several CSS rules.

Each rule is composed by 2 parts:

- the selector

- the declaration block

The selector is a string that identifies one or more elements on the page, following a special syntax that we’ll soon talk about extensively.

The declaration block contains one or more declarations, in turn composed by a property and valuepair.

Those are all the things we have in CSS.

Carefully organising properties, associating them values, and attaching those to specific elements of the page using a selector is the whole argument of this ebook.

How does CSS look like

A CSS rule set has one part called selector, and the other part called declaration. The declaration contains various rules, each composed by a property, and a value.

In this example, p is the selector, and applies one rule which sets the value 20px to the font-size property:

p {

font-size: 20px;

}

Multiple rules are stacked one after the other:

p {

font-size: 20px;

}

a {

color: blue;

}

A selector can target one or more items:

p, a {

font-size: 20px;

}

and it can target HTML tags, like above, or HTML elements that contain a certain class attribute with .my-class, or HTML elements that have a specific id attribute with #my-id.

More advanced selectors allow you to choose items whose attribute matches a specific value, or also items which respond to pseudo-classes (more on that later)

Semicolons

Every CSS rule terminates with a semicolon. Semicolons are not optional, except after the last rule. But I suggest to always use them for consistency and to avoid errors if you add another property and forget to add the semicolon on the previous line.

Formatting and indentation

There is no fixed rule for formatting. This CSS is valid:

p

{

font-size: 20px ;

}

a{color:blue;}

but a pain to see. Stick to some conventions, like the ones you see in the examples above: stick selectors and the closing brackets to the left, indent 2 spaces for each rule, have the opening bracket on the same line of the selector, separated by one space.

Correct and consistent use of spacing and indentation is a visual aid in understanding your code.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CSS

Before moving on, I want to give you a brief recap of the history of CSS.

CSS was grown out of the necessity of styling web pages. Before CSS was introduced, people wanted a way to style their web pages, which looked all very similar and “academic” back in the day. You couldn’t do much in terms of personalisation.

HTML 3.2 introduced the option of defining colors inline as HTML element attributes, and presentational tags like center and font, but that escalated quickly into a far from ideal situation.

CSS let us move everything presentation-related from the HTML to the CSS, so that HTML could get back being the format that defines the structure of the document, rather than how things should look in the browser.

CSS is continuously evolving, and CSS you used 5 years ago might just be outdated, as new idiomatic CSS techniques emerged and browsers changed.

It’s hard to imagine the times when CSS was born and how different the web was.

At the time, we had several competing browsers, the main ones being Internet Explorer or Netscape Navigator.

Pages were styled by using HTML, with special presentational tags like bold and special attributes, most of which are now deprecated.

This meant you had a limited amount of customisation opportunities.

The bulk of the styling decisions were left to the browser.

Also, you built a site specifically for one of them, because each one introduced different non-standard tags to give more power and opportunities.

Soon people realised the need for a way to style pages, in a way that would work across all browsers.

After the initial idea proposed in 1994, CSS got its first release in 1996, when the CSS Level 1 (“CSS 1”) recommendation was published.

CSS Level 2 (“CSS 2”) got published in 1998.

Since then, work began on CSS Level 3. The CSS Working Group decided to split every feature and work on it separately, in modules.

Browsers weren’t especially fast at implementing CSS. We had to wait until 2002 to have the first browser implement the full CSS specification: IE for Mac, as nicely described in this CSS Tricks post: https://css-tricks.com/look-back-history-css/

Internet Explorer implemented the box model incorrectly right from the start, which led to years of pain trying to have the same style applied consistently across browsers. We had to use various tricks and hacks to make browsers render things as we wanted.

Today things are much, much better. We can just use the CSS standards without thinking about quirks, most of the time, and CSS has never been more powerful.

We don’t have official release numbers for CSS any more now, but the CSS Working Group releases a “snapshot” of the modules that are currently considered stable and ready to be included in browsers. This is the latest snapshot, from 2018: https://www.w3.org/TR/css-2018/

CSS Level 2 is still the base for the CSS we write today, and we have many more features built on top of it.

ADDING CSS TO AN HTML PAGE

CSS is attached to an HTML page in different ways.

1: Using the link tag

The link tag is the way to include a CSS file. This is the preferred way to use CSS as it’s intended to be used: one CSS file is included by all the pages of your site, and changing one line on that file affects the presentation of all the pages in the site.

To use this method, you add a link tag with the href attribute pointing to the CSS file you want to include. You add it inside the head tag of the site (not inside the body tag):

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="myfile.css">

The rel and type attributes are required too, as they tell the browser which kind of file we are linking to.

2: using the style tag

Instead of using the link tag to point to separate stylesheet containing our CSS, we can add the CSS directly inside a style tag. This is the syntax:

<style>

...our CSS...

</style>

Using this method we can avoid creating a separate CSS file. I find this is a good way to experiment before “formalising” CSS to a separate file, or to add a special line of CSS just to a file.

3: inline styles

Inline styles are the third way to add CSS to a page. We can add a style attribute to any HTML tag, and add CSS into it.

<div style="">...</div>

Example:

<div style="background-color: yellow">...</div>

SELECTORS

A selector allows us to associate one or more declarations to one or more elements on the page.

Basic selectors

Suppose we have a p element on the page, and we want to display the words into it using the yellow color.

We can target that element using this selector p, which targets all the element using the p tag in the page. A simple CSS rule to achieve what we want is:

p {

color: yellow;

}

Every HTML tag has a corresponding selector, for example: div, span, img.

If a selector matches multiple elements, all the elements in the page will be affected by the change.

HTML elements have 2 attributes which are very commonly used within CSS to associate styling to a specific element on the page: class and id.

There is one big difference between those two: inside an HTML document you can repeat the same class value across multiple elements, but you can only use an id once. As a corollary, using classes you can select an element with 2 or more specific class names, something not possible using ids.

Classes are identified using the . symbol, while ids using the # symbol.

Example using a class:

<p class="dog-name">

Roger

</p>

.dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

Example using an id:

<p id="dog-name">

Roger

</p>

#dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

Combining selectors

So far we’ve seen how to target an element, a class or an id. Let’s introduce more powerful selectors.

Targeting an element with a class or id

You can target a specific element that has a class, or id, attached.

Example using a class:

<p class="dog-name">

Roger

</p>

p.dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

Example using an id:

<p id="dog-name">

Roger

</p>

p#dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

Why would you want to do that, if the class or id already provides a way to target that element? You might have to do that to have more specificity. We’ll see what that means later.

Targeting multiple classes

You can target an element with a specific class using .class-name, as you saw previously. You can target an element with 2 (or more) classes by combining the class names separated with a dot, without spaces.

Example:

<p class="dog-name roger">

Roger

</p>

.dog-name.roger {

color: yellow;

}

Combining classes and ids

In the same way, you can combine a class and an id.

Example:

<p class="dog-name" id="roger">

Roger

</p>

.dog-name#roger {

color: yellow;

}

Grouping selectors

You can combine selectors to apply the same declarations to multiple selectors. To do so, you separate them with a comma.

Example:

<p>

My dog name is:

</p>

<span class="dog-name">

Roger

</span>

p, .dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

You can add spaces in those declarations to make them more clear:

p,

.dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

Follow the document tree with selectors

We’ve seen how to target an element in the page by using a tag name, a class or an id.

You can create a more specific selector by combining multiple items to follow the document tree structure. For example, if you have a span tag nested inside a p tag, you can target that one without applying the style to a span tag not included in a p tag:

<span>

Hello!

</span>

<p>

My dog name is:

<span class="dog-name">

Roger

</span>

</p>

p span {

color: yellow;

}

See how we used a space between the two tokens p and span.

This works even if the element on the right is multiple levels deep.

To make the dependency strict on the first level, you can use the > symbol between the two tokens:

p > span {

color: yellow;

}

In this case, if a span is not a first children of the p element, it’s not going to have the new color applied.

Direct children will have the style applied:

<p>

<span>

This is yellow

</span>

<strong>

<span>

This is not yellow

</span>

</strong>

</p>

Adjacent sibling selectors let us style an element only if preceded by a specific element. We do so using the + operator:

Example:

p + span {

color: yellow;

}

This will assign the color yellow to all span elements preceded by a p element:

<p>This is a paragraph</p>

<span>This is a yellow span</span>

We have a lot more selectors we can use:

- attribute selectors

- pseudo class selectors

- pseudo element selectors

We’ll find all about them in the next sections.

CASCADE

Cascade is a fundamental concept of CSS. After all, it’s in the name itself, the first C of CSS — Cascading Style Sheets — it must be an important thing.

What does it mean?

Cascade is the process, or algorithm, that determines the properties applied to each element on the page. Trying to converge from a list of CSS rules that are defined in various places.

It does so taking in consideration:

- specificity

- importance

- inheritance

- order in the file

It also takes care of resolving conflicts.

Two or more competing CSS rules for the same property applied to the same element need to be elaborated according to the CSS spec, to determine which one needs to be applied.

Even if you just have one CSS file loaded by your page, there is other CSS that is going to be part of the process. We have the browser (user agent) CSS. Browsers come with a default set of rules, all different between browsers.

Then your CSS comes into play.

Then the browser applies any user stylesheet, which might also be applied by browser extensions.

All those rules come into play while rendering the page.

We’ll now see the concepts of specificity and inheritance.

SPECIFICITY

What happens when an element is targeted by multiple rules, with different selectors, that affect the same property?

For example, let’s talk about this element:

<p class="dog-name">

Roger

</p>

We can have

.dog-name {

color: yellow;

}

and another rule that targets p, which sets the color to another value:

p {

color: red;

}

And another rule that targets p.dog-name. Which rule is going to take precedence over the others, and why?

Enter specificity. The more specific rule will win. If two or more rules have the same specificity, the one that appears last wins.

Sometimes what is more specific in practice is a bit confusing to beginners. I would say it’s also confusing to experts that do not look at those rules that frequently, or simply overlook them.

How to calculate specificity

Specificity is calculated using a convention.

We have 4 slots, and each one of them starts at 0: 0 0 0 0 0. The slot at the left is the most important, and the rightmost one is the least important.

Like it works for numbers in the decimal system: 1 0 0 0 is higher than 0 1 0 0.

Slot 1

The first slot, the rightmost one, is the least important.

We increase this value when we have an element selector. An element is a tag name. If you have more than one element selector in the rule, you increment accordingly the value stored in this slot.

Examples:

p {} /* 0 0 0 1 */

span {} /* 0 0 0 1 */

p span {} /* 0 0 0 2 */

p > span {} /* 0 0 0 2 */

div p > span {} /* 0 0 0 3 */

Slot 2

The second slot is incremented by 3 things:

- class selectors

- pseudo-class selectors

- attribute selectors

Every time a rule meets one of those, we increment the value of the second column from the right.

Examples:

.name {} /* 0 0 1 0 */

.users .name {} /* 0 0 2 0 */

[href$='.pdf'] {} /* 0 0 1 0 */

:hover {} /* 0 0 1 0 */

Of course slot 2 selectors can be combined with slot 1 selectors:

div .name {} /* 0 0 1 1 */

a[href$='.pdf'] {} /* 0 0 1 1 */

.pictures img:hover {} /* 0 0 2 1 */

One nice trick with classes is that you can repeat the same class and increase the specificity. For example:

.name {} /* 0 0 1 0 */

.name.name {} /* 0 0 2 0 */

.name.name.name {} /* 0 0 3 0 */

Slot 3

Slot 3 holds the most important thing that can affect your CSS specificity in a CSS file: the id.

Every element can have an id attribute assigned, and we can use that in our stylesheet to target the element.

Examples:

#name {} /* 0 1 0 0 */

.user #name {} /* 0 1 1 0 */

#name span {} /* 0 1 0 1 */

Slot 4

Slot 4 is affected by inline styles. Any inline style will have precedence over any rule defined in an external CSS file, or inside the style tag in the page header.

Example:

<p style="color: red">Test</p> /* 1 0 0 0 */

Even if any other rule in the CSS defines the color, this inline style rule is going to be applied. Except for one case — if !important is used, which fills the slot 5.

Importance

Specificity does not matter if a rule ends with !important:

p {

font-size: 20px!important;

}

That rule will take precedence over any rule with more specificity

Adding !important in a CSS rule is going to make that rule more important than any other rule, according to the specificity rules. The only way another rule can take precedence is to have !important as well, and have higher specificity in the other less important slots.

Tips

In general you should use the amount of specificity you need, but not more. In this way, you can craft other selectors to overwrite the rules set by preceding rules without going mad.

!important is a highly debated tool that CSS offers us. Many CSS experts advocate against using it. I find myself using it especially when trying out some style and a CSS rule has so much specificity that I need to use !important to make the browser apply my new CSS.

But generally, !important should have no place in your CSS files.

Using the id attribute to style CSS is also debated a lot, since it has a very high specificity. A good alternative is to use classes instead, which have less specificity, and so they are easier to work with, and they are more powerful (you can have multiple classes for an element, and a class can be reused multiple times).

Tools to calculate the specificity

You can use the site https://specificity.keegan.st/ to perform the specificity calculation for you automatically.

It’s useful especially if you are trying to figure things out, as it can be a nice feedback tool.

INHERITANCE

When you set some properties on a selector in CSS, they are inherited by all the children of that selector.

I said some, because not all properties show this behaviour.

This happens because some properties make sense to be inherited. This helps us write CSS much more concisely, since we don’t have to explicitly set that property again on every single child.

Some other properties make more sense to not be inherited.

Think about fonts: you don’t need to apply the font-family to every single tag of your page. You set the body tag font, and every child inherits it, along with other properties.

The background-color property, on the other hand, makes little sense to be inherited.

Properties that inherit

Here is a list of the properties that do inherit. The list is non-comprehensive, but those rules are just the most popular ones you’ll likely use:

- border-collapse

- border-spacing

- caption-side

- color

- cursor

- direction

- empty-cells

- font-family

- font-size

- font-style

- font-variant

- font-weight

- font-size-adjust

- font-stretch

- font

- letter-spacing

- line-height

- list-style-image

- list-style-position

- list-style-type

- list-style

- orphans

- quotes

- tab-size

- text-align

- text-align-last

- text-decoration-color

- text-indent

- text-justify

- text-shadow

- text-transform

- visibility

- white-space

- widows

- word-break

- word-spacing

I got it from this nice Sitepoint article on CSS inheritance.

Forcing properties to inherit

What if you have a property that’s not inherited by default, and you want it to, in a child?

In the children, you set the property value to the special keyword inherit.

Example:

body {

background-color: yellow;

}

p {

background-color: inherit;

}

Forcing properties to NOT inherit

On the contrary, you might have a property inherited and you want to avoid so.

You can use the revert keyword to revert it. In this case, the value is reverted to the original value the browser gave it in its default stylesheet.

In practice this is rarely used, and most of the times you’ll just set another value for the property to overwrite that inherited value.

Other special values

In addition to the inherit and revert special keywords we just saw, you can also set any property to:

initial: use the default browser stylesheet if available. If not, and if the property inherits by default, inherit the value. Otherwise do nothing.unset: if the property inherits by default, inherit. Otherwise do nothing.

IMPORT

From any CSS file you can import another CSS file using the @import directive.

Here is how you use it:

@import url(myfile.css)

url() can manage absolute or relative URLs.

One important thing you need to know is that @import directives must be put before any other CSS in the file, or they will be ignored.

You can use media descriptors to only load a CSS file on the specific media:

@import url(myfile.css) all;

@import url(myfile-screen.css) screen;

@import url(myfile-print.css) print;

ATTRIBUTE SELECTORS

We already introduced several of the basic CSS selectors: using element selectors, class, id, how to combine them, how to target multiple classes, how to style several selectors in the same rule, how to follow the page hierarchy with child and direct child selectors, and adjacent siblings.

In this section we’ll analyze attribute selectors, and we’ll talk about pseudo class and pseudo element selectors in the next 2 sections.

Attribute presence selectors

The first selector type is the attribute presence selector.

We can check if an element has an attribute using the [] syntax. p[id] will select all p tags in the page that have an id attribute, regardless of its value:

p[id] {

/* ... */

}

Exact attribute value selectors

Inside the brackets you can check the attribute value using =, and the CSS will be applied only if the attribute matches the exact value specified:

p[id="my-id"] {

/* ... */

}

Match an attribute value portion

While = lets us check for exact value, we have other operators:

*=checks if the attribute contains the partial^=checks if the attribute starts with the partial$=checks if the attribute ends with the partial|=checks if the attribute starts with the partial and it’s followed by a dash (common in classes, for example), or just contains the partial~=checks if the partial is contained in the attribute, but separated by spaces from the rest

All the checks we mentioned are case sensitive.

If you add an i just before the closing bracket, the check will be case insensitive. It’s supported in many browsers but not in all, check https://caniuse.com/#feat=css-case-insensitive.

PSEUDO-CLASSES

Pseudo classes are predefined keywords that are used to select an element based on its state, or to target a specific child.

They start with a single colon :.

They can be used as part of a selector, and they are very useful to style active or visited links, for example, change the style on hover, focus, or target the first child, or odd rows. Very handy in many cases.

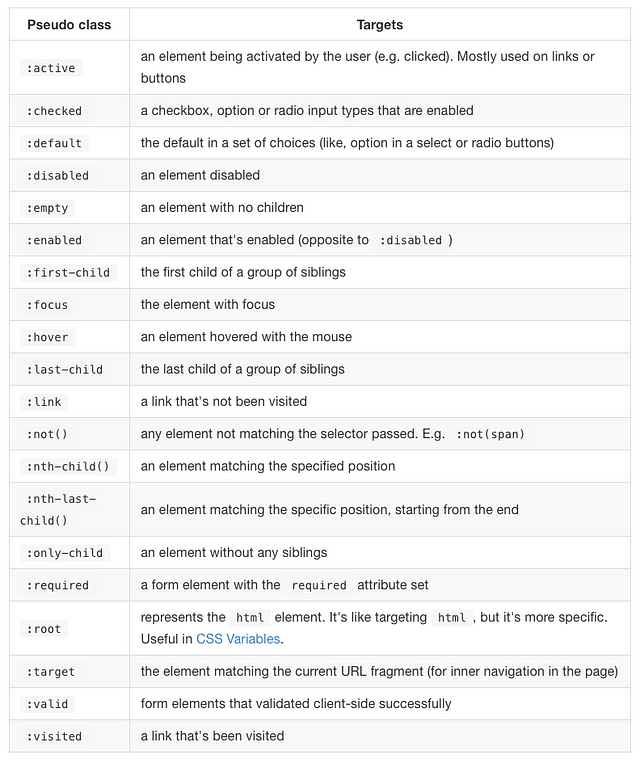

These are the most popular pseudo classes you will likely use:

Let’s do an example. A common one, actually. You want to style a link, so you create a CSS rule to target the a element:

a {

color: yellow;

}

Things seem to work fine, until you click one link. The link goes back to the predefined color (blue) when you click it. Then when you open the link and go back to the page, now the link is blue.

Why does that happen?

Because the link when clicked changes state, and goes in the :active state. And when it’s been visited, it is in the :visited state. Forever, until the user clears the browsing history.

So, to correctly make the link yellow across all states, you need to write

a,

a:visited,

a:active {

color: yellow;

}

:nth-child() deserves a special mention. It can be used to target odd or even children with :nth-child(odd) and :nth-child(even).

It is commonly used in lists to color odd lines differently from even lines:

ul:nth-child(odd) {

color: white;

background-color: black;

}

You can also use it to target the first 3 children of an element with :nth-child(-n+3). Or you can style 1 in every 5 elements with :nth-child(5n).

Some pseudo classes are just used for printing, like :first, :left, :right, so you can target the first page, all the left pages, and all the right pages, which are usually styled slightly differently.

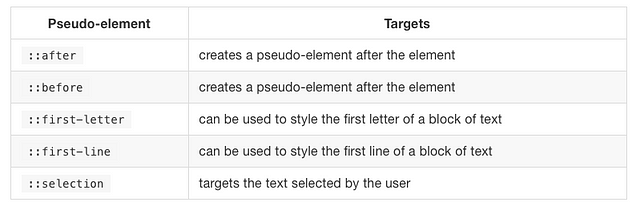

PSEUDO-ELEMENTS

Pseudo-elements are used to style a specific part of an element.

They start with a double colon ::.

Sometimes you will spot them in the wild with a single colon, but this is only a syntax supported for backwards compatibility reasons. You should use 2 colons to distinguish them from pseudo-classes.

::beforeand::afterare probably the most used pseudo-elements. They are used to add content before or after an element, like icons for example.

Here’s the list of the pseudo-elements:

Let’s do an example. Say you want to make the first line of a paragraph slightly bigger in font size, a common thing in typography:

p::first-line {

font-size: 2rem;

}

Or maybe you want the first letter to be bolder:

p::first-letter {

font-weight: bolder;

}

::after and ::before are a bit less intuitive. I remember using them when I had to add icons using CSS.

You specify the content property to insert any kind of content after or before an element:

p::before {

content: url(/myimage.png);

}

.myElement::before {

content: "Hey Hey!";

}

COLORS

By default an HTML page is rendered by web browsers quite sadly in terms of the colors used.

We have a white background, black color, and blue links. That’s it.

Luckily CSS gives us the ability to add colors to our designs.

We have these properties:

colorbackground-colorborder-color

All of them accept a color value, which can be in different forms.

Named colors

First, we have CSS keywords that define colors. CSS started with 16, but today there is a huge number of colors names:

aliceblueantiquewhiteaquaaquamarineazurebeigebisqueblackblanchedalmondbluebluevioletbrownburlywoodcadetbluechartreusechocolatecoralcornflowerbluecornsilkcrimsoncyandarkbluedarkcyandarkgoldenroddarkgraydarkgreendarkgreydarkkhakidarkmagentadarkolivegreendarkorangedarkorchiddarkreddarksalmondarkseagreendarkslatebluedarkslategraydarkslategreydarkturquoisedarkvioletdeeppinkdeepskybluedimgraydimgreydodgerbluefirebrickfloralwhiteforestgreenfuchsiagainsboroghostwhitegoldgoldenrodgraygreengreenyellowgreyhoneydewhotpinkindianredindigoivorykhakilavenderlavenderblushlawngreenlemonchiffonlightbluelightcorallightcyanlightgoldenrodyellowlightgraylightgreenlightgreylightpinklightsalmonlightseagreenlightskybluelightslategraylightslategreylightsteelbluelightyellowlimelimegreenlinenmagentamaroonmediumaquamarinemediumbluemediumorchidmediumpurplemediumseagreenmediumslatebluemediumspringgreenmediumturquoisemediumvioletredmidnightbluemintcreammistyrosemoccasinnavajowhitenavyoldlaceoliveolivedraborangeorangeredorchidpalegoldenrodpalegreenpaleturquoisepalevioletredpapayawhippeachpuffperupinkplumpowderbluepurplerebeccapurpleredrosybrownroyalbluesaddlebrownsalmonsandybrownseagreenseashellsiennasilverskyblueslateblueslategrayslategreysnowspringgreensteelbluetantealthistletomatoturquoisevioletwheatwhitewhitesmokeyellowyellowgreen

plus tranparent, and currentColor which points to the color property, for example it’s useful to make the border-color inherit it.

They are defined in the CSS Color Module, Level 4. They are case insensitive.

Wikipedia has a nice table which lets you pick the perfect color by its name.

Named colors are not the only option.

RGB and RGBa

You can use the rgb() function to calculate a color from its RGB notation, which sets the color based on its red-green-blue parts. From 0 to 255:

p {

color: rgb(255, 255, 255); /* white */

background-color: rgb(0, 0, 0); /* black */

}

rgba() lets you add the alpha channel to enter a transparent part. That can be a number from 0 to 1:

p {

background-color: rgb(0, 0, 0, 0.5);

}

Hexadecimal notation

Another option is to express the RGB parts of the colors in the hexadecimal notation, which is composed by 3 blocks.

Black, which is rgb(0,0,0) is expressed as #000000 or #000 (we can shortcut the 2 numbers to 1 if they are equal).

White, rgb(255,255,255) can be expressed as #ffffff or #fff.

The hexadecimal notation lets us express a number from 0 to 255 in just 2 digits, since they can go from 0 to “15” (f).

We can add the alpha channel by adding 1 or 2 more digits at the end, for example #00000033. Not all browsers support the shortened notation, so use all 6 digits to express the RGB part.

HSL and HSLa

This is a more recent addition to CSS.

HSL = Hue Saturation Lightness.

In this notation, black is hsl(0, 0%, 0%) and white is hsl(0, 0%, 100%).

If you are more familiar with HSL than RGB because of your past knowledge, you can definitely use that.

You also have hsla() which adds the alpha channel to the mix, again a number from 0 to 1: hsl(0, 0%, 0%, 0.5)

UNITS

One of the things you’ll use every day in CSS are units. They are used to set lengths, paddings, margins, align elements and so on.

Things like px, em, rem, or percentages.

They are everywhere. There are some obscure ones, too. We’ll go through each of them in this section.

Pixels

The most widely used measurement unit. A pixel does not actually correlate to a physical pixel on your screen, as that varies, a lot, by device (think high-DPI devices vs non-retina devices).

There is a convention that make this unit work consistently across devices.

Percentages

Another very useful measure, percentages let you specify values in percentages of that parent element’s corresponding property.

Example:

.parent {

width: 400px;

}

.child {

width: 50%; /* = 200px */

}

Real-world measurement units

We have those measurement units which are translated from the outside world. Mostly useless on screen, they can be useful for print stylesheets. They are:

cma centimeter (maps to 37.8 pixels)mma millimeter (0.1cm)qa quarter of a millimeterinan inch (maps to 96 pixels)pta point (1 inch = 72 points)pca pica (1 pica = 12 points)

Relative units

emis the value assigned to that element’sfont-size, therefore its exact value changes between elements. It does not change depending on the font used, just on the font size. In typography this measures the width of themletter.remis similar toem, but instead of varying on the current element font size, it uses the root element (html) font size. You set that font size once, andremwill be a consistent measure across all the page.exis likeem, but inserted of measuring the width ofm, it measures the height of thexletter. It can change depending on the font used, and on the font size.chis likeexbut instead of measuring the height ofxit measures the width of0(zero).

Viewport units

vwthe viewport width unit represents a percentage of the viewport width.50vwmeans 50% of the viewport width.vhthe viewport height unit represents a percentage of the viewport height.50vhmeans 50% of the viewport height.vminthe viewport minimum unit represents the minimum between the height or width in terms of percentage.30vminis the 30% of the current width or height, depending which one is smallervmaxthe viewport maximum unit represents the maximum between the height or width in terms of percentage.30vmaxis the 30% of the current width or height, depending which one is bigger

Fraction units

fr are fraction units, and they are used in CSS Grid to divide space into fractions.

We’ll talk about them in the context of CSS Grid later on.

URL

When we talk about background images, @import, and more, we use the url() function to load a resource:

div {

background-image: url(test.png);

}

In this case I used a relative URL, which searches the file in the folder where the CSS file is defined.

I could go one level back

div {

background-image: url(../test.png);

}

or go into a folder

div {

background-image: url(subfolder/test.png);

}

Or I could load a file starting from the root of the domain where the CSS is hosted:

div {

background-image: url(/test.png);

}

Or I could use an absolute URL to load an external resource:

div {

background-image: url(https://mysite.com/test.png);

}

CALC

The calc() function lets you perform basic math operations on values, and it’s especially useful when you need to add or subtract a length value from a percentage.

This is how it works:

div {

max-width: calc(80% - 100px)

}

It returns a length value, so it can be used anywhere you expect a pixel value.

You can perform

- additions using

+ - subtractions using

- - multiplication using

* - division using

/

One caveat: with addition and subtraction, the space around the operator is mandatory, otherwise it does not work as expected.

Examples:

div {

max-width: calc(50% / 3)

}

div {

max-width: calc(50% + 3px)

}

BACKGROUNDS

The background of an element can be changed using several CSS properties:

background-colorbackground-imagebackground-clipbackground-positionbackground-originbackground-repeatbackground-attachmentbackground-size

and the shorthand property background, which allows us to shorten definitions and group them on a single line.

background-color accepts a color value, which can be one of the color keywords, or an rgb or hsl value:

p {

background-color: yellow;

}

div {

background-color: #333;

}

Instead of using a color, you can use an image as background to an element, by specifying the image location URL:

div {

background-image: url(image.png);

}

background-clip lets you determine the area used by the background image, or color. The default value is border-box, which extends up to the border outer edge.

Other values are

padding-boxto extend the background up to the padding edge, without the bordercontent-boxto extend the background up to the content edge, without the paddinginheritto apply the value of the parent

When using an image as background you will want to set the position of the image placement using the background-position property: left, right, center are all valid values for the X axis, and top, bottom for the Y axis:

div {

background-position: top right;

}

If the image is smaller than the background, you need to set the behavior using background-repeat. Should it repeat-x, repeat-y or repeat on all the axes? This last one is the default value. Another value is no-repeat.

background-origin lets you choose where the background should be applied: to the entire element including padding (default) using padding-box, to the entire element including the border using border-box, to the element without the padding using content-box.

With background-attachment we can attach the background to the viewport, so that scrolling will not affect the background:

div {

background-attachment: fixed;

}

By default the value is scroll. There is another value, local. The best way to visualize their behavior is this Codepen.

The last background property is background-size. We can use 3 keywords: auto, cover and contain. auto is the default.

cover expands the image until the entire element is covered by the background.

contain stops expanding the background image when one dimension (x or y) covers the whole smallest edge of the image, so it’s fully contained into the element.

You can also specify a length value, and if so it sets the width of the background image (and the height is automatically defined):

div {

background-size: 100%;

}

If you specify 2 values, one is the width and the second is the height:

div {

background-size: 800px 600px;

}

The shorthand property background allows to shorten definitions and group them on a single line.

This is an example:

div {

background: url(bg.png) top left no-repeat;

}

If you use an image, and the image could not be loaded, you can set a fallback color:

div {

background: url(image.png) yellow;

}

You can also set a gradient as background:

div {

background: linear-gradient(#fff, #333);

}

COMMENTS

CSS gives you the ability to write comments in a CSS file, or in the style tag in the page header

The format is the /* this is a comment */ C-style (or JavaScript-style, if you prefer) comments.

This is a multiline comment. Until you add the closing */ token, the all the lines found after the opening one are commented.

Example:

#name { display: block; } /* Nice rule! */

/* #name { display: block; } */

#name {

display: block; /*

color: red;

*/

}

CSS does not have inline comments, like // in C or JavaScript.

Pay attention though — if you add // before a rule, the rule will not be applied, looking like the comment worked. In reality, CSS detected a syntax error and due to how it works it ignored the line with the error, and went straight to the next line.

Knowing this approach lets you purposefully write inline comments, although you have to be careful because you can’t add random text like you can in a block comment.

For example:

// Nice rule!

#name { display: block; }

In this case, due to how CSS works, the #name rule is actually commented out. You can find more details here if you find this interesting. To avoid shooting yourself in the foot, just avoid using inline comments and rely on block comments.

CUSTOM PROPERTIES

In the last few years CSS preprocessors have had a lot of success. It was very common for greenfield projects to start with Less or Sass. And it’s still a very popular technology.

The main benefits of those technologies are, in my opinion:

- They allow you to nest selectors

- The provide an easy imports functionality

- They give you variables

Modern CSS has a new powerful feature called CSS Custom Properties, also commonly known as CSS Variables.

CSS is not a programming language like JavaScript, Python, PHP, Ruby or Go where variables are key to do something useful. CSS is very limited in what it can do, and it’s mainly a declarative syntax to tell browsers how they should display an HTML page.

But a variable is a variable: a name that refers to a value, and variables in CSS help reduce repetition and inconsistencies in your CSS, by centralizing the values definition.

And it introduces a unique feature that CSS preprocessors won’t ever have: you can access and change the value of a CSS Variable programmatically using JavaScript.

The basics of using variables

A CSS Variable is defined with a special syntax, prepending two dashes to a name (--variable-name), then a colon and a value. Like this:

:root {

--primary-color: yellow;

}

(more on :root later)

You can access the variable value using var():

p {

color: var(--primary-color)

}

The variable value can be any valid CSS value, for example:

:root {

--default-padding: 30px 30px 20px 20px;

--default-color: red;

--default-background: #fff;

}

Create variables inside any element

CSS Variables can be defined inside any element. Some examples:

:root {

--default-color: red;

}

body {

--default-color: red;

}

main {

--default-color: red;

}

p {

--default-color: red;

}

span {

--default-color: red;

}

a:hover {

--default-color: red;

}

What changes in those different examples is the scope.

Variables scope

Adding variables to a selector makes them available to all the children of it.

In the example above you saw the use of :root when defining a CSS variable:

:root {

--primary-color: yellow;

}

:root is a CSS pseudo-class that identifies the root element of a tree.

In the context of an HTML document, using the :root selector points to the html element, except that :root has higher specificity (takes priority).

In the context of an SVG image, :root points to the svg tag.

Adding a CSS custom property to :root makes it available to all the elements in the page.

If you add a variable inside a .container selector, it’s only going to be available to children of .container:

.container {

--secondary-color: yellow;

}

and using it outside of this element is not going to work.

Variables can be reassigned:

:root {

--primary-color: yellow;

}

.container {

--primary-color: blue;

}

Outside .container, --primary-color will be yellow, but inside it will be blue.

You can also assign or overwrite a variable inside the HTML using inline styles:

<main style="--primary-color: orange;">

<!-- ... -->

</main>

CSS Variables follow the normal CSS cascading rules, with precedence set according to specificity.#### Interacting with a CSS Variable value using JavaScript

The coolest thing with CSS Variables is the ability to access and edit them using JavaScript.

Here’s how you set a variable value using plain JavaScript:

const element = document.getElementById('my-element')

element.style.setProperty('--variable-name', 'a-value')

This code below can be used to access a variable value instead, in case the variable is defined on :root:

const styles = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement)

const value = String(styles.getPropertyValue('--variable-name')).trim()

Or, to get the style applied to a specific element, in case of variables set with a different scope:

const element = document.getElementById('my-element')

const styles = getComputedStyle(element)

const value = String(styles.getPropertyValue('--variable-name')).trim()

Handling invalid values

If a variable is assigned to a property which does not accept the variable value, it’s considered invalid.

For example you might pass a pixel value to a position property, or a rem value to a color property.

In this case the line is considered invalid and is ignored.

Browser support

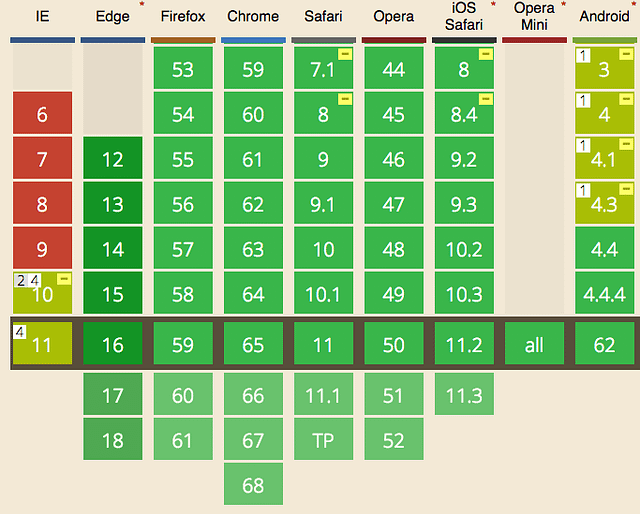

Browser support for CSS Variables is very good, according to Can I Use.

CSS Variables are here to stay, and you can use them today if you don’t need to support Internet Explorer and old versions of the other browsers.

If you need to support older browsers you can use libraries like PostCSS or Myth, but you’ll lose the ability to interact with variables via JavaScript or the Browser Developer Tools, as they are transpiled to good old variable-less CSS (and as such, you lose most of the power of CSS Variables).

CSS Variables are case sensitive

This variable:

--width: 100px;

is different than this one:

--Width: 100px;

Math in CSS Variables

To do math in CSS Variables, you need to use calc(), for example:

:root {

--default-left-padding: calc(10px * 2);

}

Media queries with CSS Variables

Nothing special here. CSS Variables normally apply to media queries:

body {

--width: 500px;

}

@media screen and (max-width: 1000px) and (min-width: 700px) {

--width: 800px;

}

.container {

width: var(--width);

}

Setting a fallback value for var()

var() accepts a second parameter, which is the default fallback value when the variable value is not set:

.container {

margin: var(--default-margin, 30px);

}

FONTS

At the dawn of the web you only had a handful of fonts you could choose from.

Thankfully today you can load any kind of font on your pages.

CSS has gained many nice capabilities over the years in regards to fonts.

The font property is the shorthand for a number of properties:

font-familyfont-weightfont-stretchfont-stylefont-size

Let’s see each one of them and then we’ll cover font.

Then we’ll talk about how to load custom fonts, using @import or @font-face, or by loading a font stylesheet.

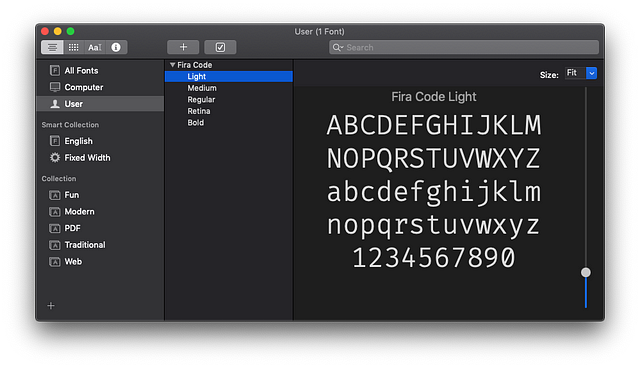

font-family

Sets the font family that the element will use.

Why “family”? Because what we know as a font is actually composed of several sub-fonts which provide all the style (bold, italic, light…) we need.

Here’s an example from my Mac’s Font Book app — the Fira Code font family hosts several dedicated fonts underneath:

This property lets you select a specific font, for example:

body {

font-family: Helvetica;

}

You can set multiple values, so the second option will be used if the first cannot be used for some reason (if it’s not found on the machine, or the network connection to download the font failed, for example):

body {

font-family: Helvetica, Arial;

}

I used some specific fonts up to now, ones we call Web Safe Fonts, as they are pre-installed on different operating systems.

We divide them in Serif, Sans-Serif, and Monospace fonts. Here’s a list of some of the most popular ones:

Serif

- Georgia

- Palatino

- Times New Roman

- Times

Sans-Serif

- Arial

- Helvetica

- Verdana

- Geneva

- Tahoma

- Lucida Grande

- Impact

- Trebuchet MS

- Arial Black

Monospace

- Courier New

- Courier

- Lucida Console

- Monaco

You can use all of those as font-family properties, but they are not guaranteed to be there for every system. Others exist, too, with a varying level of support.

You can also use generic names:

sans-serifa font without ligaturesserifa font with ligaturesmonospacea font especially good for codecursiveused to simulate handwritten piecesfantasythe name says it all

Those are typically used at the end of a font-family definition, to provide a fallback value in case nothing else can be applied:

body {

font-family: Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

}

font-weight

This property sets the width of a font. You can use those predefined values:

- normal

- bold

- bolder (relative to the parent element)

- lighter (relative to the parent element)

Or using the numeric keywords

- 100

- 200

- 300

- 400, mapped to

normal - 500

- 600

- 700 mapped to

bold - 800

- 900

where 100 is the lightest font, and 900 is the boldest.

Some of those numeric values might not map to a font, because that must be provided in the font family. When one is missing, CSS makes that number be at least as bold as the preceding one, so you might have numbers that point to the same font.

font-stretch

Allows you to choose a narrow or wide face of the font, if available.

This is important: the font must be equipped with different faces.

Values allowed are, from narrower to wider:

ultra-condensedextra-condensedcondensedsemi-condensednormalsemi-expandedexpandedextra-expandedultra-expanded

font-style

Allows you to apply an italic style to a font:

p {

font-style: italic;

}

This property also allows the values oblique and normal. There is very little, if any, difference between using italic and oblique. The first is easier to me, as HTML already offers an i element which means italic.

font-size

This property is used to determine the size of fonts.

You can pass 2 kinds of values:

- a length value, like

px,em,remetc, or a percentage - a predefined value keyword

In the second case, the values you can use are:

- xx-small

- x-small

- small

- medium

- large

- x-large

- xx-large

- smaller (relative to the parent element)

- larger (relative to the parent element)

Usage:

p {

font-size: 20px;

}

li {

font-size: medium;

}

font-variant

This property was originally used to change the text to small caps, and it had just 3 valid values:

normalinheritsmall-caps

Small caps means the text is rendered in “smaller caps” beside its uppercase letters.

font

The font property lets you apply different font properties in a single one, reducing the clutter.

We must at least set 2 properties, font-size and font-family, the others are optional:

body {

font: 20px Helvetica;

}

If we add other properties, they need to be put in the correct order.

This is the order:

font: <font-stretch> <font-style> <font-variant> <font-weight> <font-size> <line-height> <font-family>;

Example:

body {

font: italic bold 20px Helvetica;

}

section {

font: small-caps bold 20px Helvetica;

}

Loading custom fonts using @font-face

@font-face lets you add a new font family name, and map it to a file that holds a font.

This font will be downloaded by the browser and used in the page, and it’s been such a fundamental change to typography on the web — we can now use any font we want.

We can add @font-face declarations directly into our CSS, or link to a CSS dedicated to importing the font.

In our CSS file we can also use @import to load that CSS file.

A @font-face declaration contains several properties we use to define the font, including src, the URI (one or more URIs) to the font. This follows the same-origin policy, which means fonts can only be downloaded form the current origin (domain + port + protocol).

Fonts are usually in the formats

woff(Web Open Font Format)woff2(Web Open Font Format 2.0)eot(Embedded Open Type)otf(OpenType Font)ttf(TrueType Font)

The following properties allow us to define the properties to the font we are going to load, as we saw above:

font-familyfont-weightfont-stylefont-stretch

A note on performance

Of course loading a font has performance implications which you must consider when creating the design of your page.

TYPOGRAPHY

We already talked about fonts, but there’s more to styling text.

In this section we’ll talk about the following properties:

text-transformtext-decorationtext-alignvertical-alignline-heighttext-indenttext-align-lastword-spacingletter-spacingtext-shadowwhite-spacetab-sizewriting-modehyphenstext-orientationdirectionline-breakword-break

text-transform

This property can transform the case of an element.

There are 4 valid values:

capitalizeto uppercase the first letter of each worduppercaseto uppercase all the textlowercaseto lowercase all the textnoneto disable transforming the text, used to avoid inheriting the property

Example:

p {

text-transform: uppercase;

}

text-decoration

This property is sed to add decorations to the text, including

underlineoverlineline-throughblinknone

Example:

p {

text-decoration: underline;

}

You can also set the style of the decoration, and the color.

Example:

p {

text-decoration: underline dashed yellow;

}

Valid style values are solid, double, dotted, dashed, wavy.

You can do all in one line, or use the specific properties:

text-decoration-linetext-decoration-colortext-decoration-style

Example:

p {

text-decoration-line: underline;

text-decoration-color: yellow;

text-decoration-style: dashed;

}

text-align

By default text align has the start value, meaning the text starts at the “start”, origin 0, 0 of the box that contains it. This means top left in left-to-right languages, and top right in right-to-left languages.

Possible values are start, end, left, right, center, justify (nice to have a consistent spacing at the line ends):

p {

text-align: right;

}

vertical-align

Determines how inline elements are vertically aligned.

We have several values for this property. First we can assign a length or percentage value. Those are used to align the text in a position higher or lower (using negative values) than the baseline of the parent element.

Then we have the keywords:

baseline(the default), aligns the baseline to the baseline of the parent elementsubmakes an element subscripted, simulating thesubHTML element resultsupermakes an element superscripted, simulating thesupHTML element resulttopalign the top of the element to the top of the linetext-topalign the top of the element to the top of the parent element fontmiddlealign the middle of the element to the middle of the line of the parentbottomalign the bottom of the element to the bottom of the linetext-bottomalign the bottom of the element to the bottom of the parent element font

line-height

This allows you to change the height of a line. Each line of text has a certain font height, but then there is additional spacing vertically between the lines. That’s the line height:

p {

line-height: 0.9rem;

}

text-indent

Indent the first line of a paragraph by a set length, or a percentage of the paragraph width:

p {

text-indent: -10px;

}

text-align-last

By default the last line of a paragraph is aligned following the text-align value. Use this property to change that behavior:

p {

text-align-last: right;

}

word-spacing

Modifies the spacing between each word.

You can use the normal keyword, to reset inherited values, or use a length value:

p {

word-spacing: 2px;

}

span {

word-spacing: -0.2em;

}

letter-spacing

Modifies the spacing between each letter.

You can use the normal keyword, to reset inherited values, or use a length value:

p {

letter-spacing: 0.2px;

}

span {

letter-spacing: -0.2em;

}

text-shadow

Apply a shadow to the text. By default the text has now shadow.

This property accepts an optional color, and a set of values that set

- the X offset of the shadow from the text

- the Y offset of the shadow from the text

- the blur radius

If the color is not specified, the shadow will use the text color.

Examples:

p {

text-shadow: 0.2px 2px;

}

span {

text-shadow: yellow 0.2px 2px 3px;

}

white-space

Sets how CSS handles the white space, new lines and tabs inside an element.

Valid values that collapse white space are:

normalcollapses white space. Adds new lines when necessary as the text reaches the container endnowrapcollapses white space. Does not add a new line when the text reaches the end of the container, and suppresses any line break added to the textpre-linecollapses white space. Adds new lines when necessary as the text reaches the container end

Valid values that preserve white space are:

prepreserves white space. Does not add a new line when the text reaches the end of the container, but preserves line break added to the textpre-wrappreserves white space. Adds new lines when necessary as the text reaches the container end

tab-size

Sets the width of the tab character. By default it’s 8, and you can set an integer value that sets the character spaces it takes, or a length value:

p {

tab-size: 2;

}

span {

tab-size: 4px;

}

writing-mode

Defines whether lines of text are laid out horizontally or vertically, and the direction in which blocks progress.

The values you can use are

horizontal-tb(default)vertical-rlcontent is laid out vertically. New lines are put on the left of the previousvertical-lrcontent is laid out vertically. New lines are put on the right of the previous

hyphens

Determines if hyphens should be automatically added when going to a new line.

Valid values are

none(default)manualonly add an hyphen when there is already a visible hyphen or a hidden hyphen (a special character)autoadd hyphens when determined the text can have a hyphen.

text-orientation

When writing-mode is in a vertical mode, determines the orientation of the text.

Valid values are

mixedis the default, and if a language is vertical (like Japanese) it preserves that orientation, while rotating text written in western languagesuprightmakes all text be vertically orientedsidewaysmakes all text horizontally oriented

direction

Sets the direction of the text. Valid values are ltr and rtl:

p {

direction: rtl;

}

word-break

This property specifies how to break lines within words.

normal(default) means the text is only broken between words, not inside a wordbreak-allthe browser can break a word (but no hyphens are added)keep-allsuppress soft wrapping. Mostly used for CJK (Chinese/Japanese/Korean) text.

Speaking of CJK text, the property line-break is used to determine how text lines break. I’m not an expert with those languages, so I will avoid covering it.

overflow-wrap

If a word is too long to fit a line, it can overflow outside of the container.

This property is also known as

<em>word-wrap</em>, although that is non-standard (but still works as an alias)

This is the default behavior (overflow-wrap: normal;).

We can use:

p {

overflow-wrap: break-word;

}

to break it at the exact length of the line, or

p {

overflow-wrap: anywhere;

}

if the browser sees there’s a soft wrap opportunity somewhere earlier. No hyphens are added, in any case.

This property is very similar to word-break. We might want to choose this one on western languages, while word-break has special treatment for non-western languages.

BOX MODEL

Every CSS element is essentially a box. Every element is a generic box.

The box model explains the sizing of the elements based on a few CSS properties.

From the inside to the outside, we have:

- the content area

- padding

- border

- margin

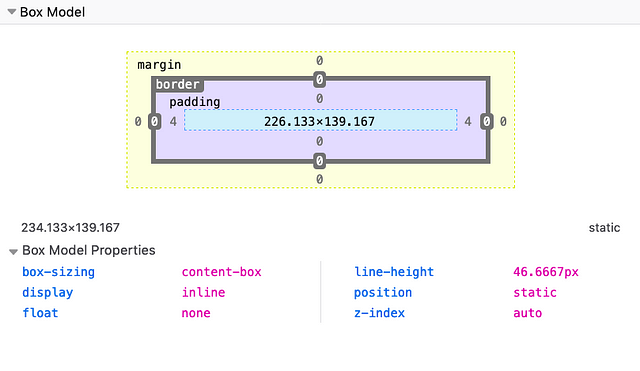

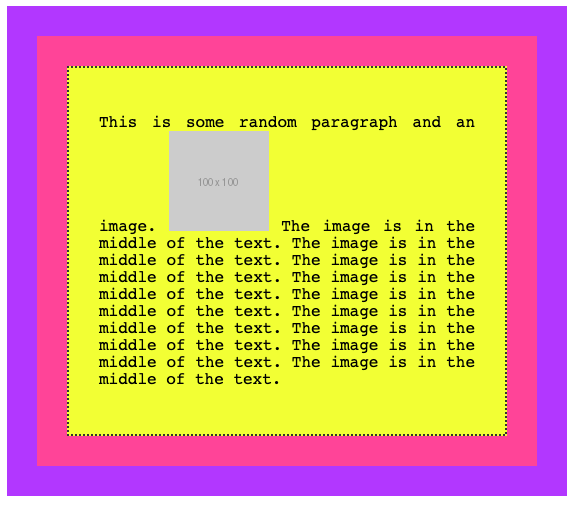

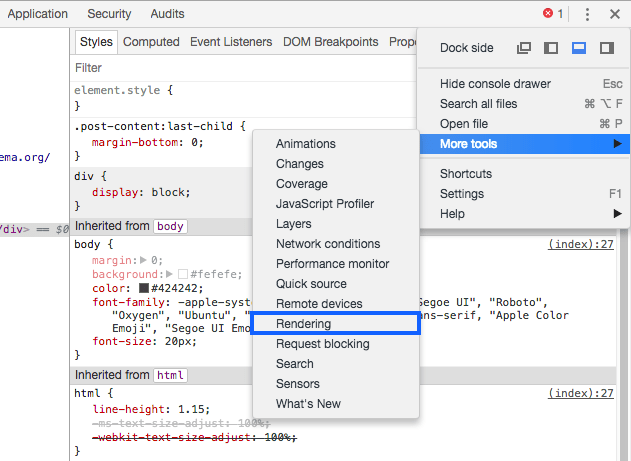

The best way to visualize the box model is to open the browser DevTools and check how it is displayed:

Here you can see how Firefox tells me the properties of a span element I highlighted. I right-clicked on it, pressed Inspect Element, and went to the Layout panel of the DevTools.

See, the light blue space is the content area. Surrounding it there is the padding, then the border and finally the margin.

By default, if you set a width (or height) on the element, that is going to be applied to the content area. All the padding, border, and margin calculations are done outside of the value, so you have to keep this in mind when you do your calculation.

Later you’ll see how you can change this behavior using Box Sizing.

BORDER

The border is a thin layer between padding and margin. By editing the border, you can make elements draw their perimeter on screen.

You can work on borders by using those properties:

border-styleborder-colorborder-width

The property border can be used as a shorthand for all those properties.

border-radius is used to create rounded corners.

You also have the ability to use images as borders, an ability given to you by border-image and its specific separate properties:

border-image-sourceborder-image-sliceborder-image-widthborder-image-outsetborder-image-repeat

Let’s start with border-style.

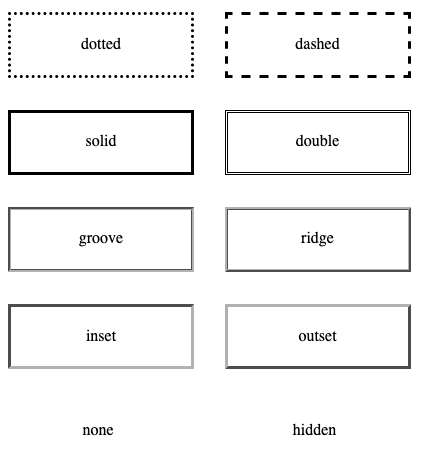

The border style

The border-style property lets you choose the style of the border. The options you can use are:

dotteddashedsoliddoublegrooveridgeinsetoutsetnonehidden

Check out this Codepen for a live example.

The default for the style is none, so to make the border appear at all you need to change it to something else. solid is a good choice most of the time.

You can set a different style for each edge using the properties

border-top-styleborder-right-styleborder-bottom-styleborder-left-style

or you can use border-style with multiple values to define them, using the usual Top-Right-Bottom-Left order:

p {

border-style: solid dotted solid dotted;

}

The border width

border-width is used to set the width of the border.

You can use one of the pre-defined values:

thinmedium(the default value)thick

or express a value in pixels, em or rem or any other valid length value.

Example:

p {

border-width: 2px;

}

You can set the width of each edge (Top-Right-Bottom-Left) separately by using 4 values:

p {

border-width: 2px 1px 2px 1px;

}

or you can use the specific edge properties border-top-width, border-right-width, border-bottom-width, border-left-width.

The border color

border-color is used to set the color of the border.

If you don’t set a color, the border by default is colored using the color of the text in the element.

You can pass any valid color value to border-color.

Example:

p {

border-color: yellow;

}

You can set the color of each edge (Top-Right-Bottom-Left) separately by using 4 values:

p {

border-color: black red yellow blue;

}

or you can use the specific edge properties border-top-color, border-right-color, border-bottom-color, border-left-color.

The border shorthand property

Those 3 properties mentioned, border-width, border-style and border-color can be set using the shorthand property border.

Example:

p {

border: 2px black solid;

}

You can also use the edge-specific properties border-top, border-right, border-bottom, border-left.

Example:

p {

border-left: 2px black solid;

border-right: 3px red dashed;

}

The border radius

border-radius is used to set rounded corners to the border. You need to pass a value that will be used as the radius of the circle that will be used to round the border.

Usage:

p {

border-radius: 3px;

}

You can also use the edge-specific properties border-top-left-radius, border-top-right-radius, border-bottom-left-radius, border-bottom-right-radius.

Using images as borders

One very cool thing with borders is the ability to use images to style them. This lets you go very creative with borders.

We have 5 properties:

border-image-sourceborder-image-sliceborder-image-widthborder-image-outsetborder-image-repeat

and the shorthand border-image. I won’t go in much details here as images as borders would need a more in-depth coverage as what I can do in this little chapter. I recommend reading the CSS Tricks almanac entry on border-image for more information.

PADDING

The padding CSS property is commonly used in CSS to add space in the inner side of an element.

Remember:

marginadds space outside an element borderpaddingadds space inside an element border

Specific padding properties

padding has 4 related properties that alter the padding of a single edge at once:

padding-toppadding-rightpadding-bottompadding-left

The usage of those is very simple and cannot be confused, for example:

padding-left: 30px;

padding-right: 3em;

Using the padding shorthand

padding is a shorthand to specify multiple padding values at the same time, and depending on the number of values entered, it behaves differently.

1 value

Using a single value applies that to all the paddings: top, right, bottom, left.

padding: 20px;

2 values

Using 2 values applies the first to bottom & top, and the second to left & right.

padding: 20px 10px;

3 values

Using 3 values applies the first to top, the second to left & right, the third to bottom.

padding: 20px 10px 30px;

4 values

Using 4 values applies the first to top, the second to right, the third to bottom, the fourth to left.

padding: 20px 10px 5px 0px;

So, the order is top-right-bottom-left.

Values accepted

padding accepts values expressed in any kind of length unit, the most common ones are px, em, rem, but many others exist.

MARGIN

The margin CSS property is commonly used in CSS to add space around an element.

Remember:

marginadds space outside an element borderpaddingadds space inside an element border

Specific margin properties

margin has 4 related properties that alter the margin of a single edge at once:

margin-topmargin-rightmargin-bottommargin-left

The usage of those is very simple and cannot be confused, for example:

margin-left: 30px;

margin-right: 3em;

Using the margin shorthand

margin is a shorthand to specify multiple margins at the same time, and depending on the number of values entered, it behaves differently.

1 value

Using a single value applies that to all the margins: top, right, bottom, left.

margin: 20px;

2 values

Using 2 values applies the first to bottom & top, and the second to left & right.

margin: 20px 10px;

3 values

Using 3 values applies the first to top, the second to left & right, the third to bottom.

margin: 20px 10px 30px;

4 values

Using 4 values applies the first to top, the second to right, the third to bottom, the fourth to left.

margin: 20px 10px 5px 0px;

So, the order is top-right-bottom-left.

Values accepted

margin accepts values expressed in any kind of length unit, the most common ones are px, em, rem, but many others exist.

It also accepts percentage values, and the special value auto.

Using auto to center elements

auto can be used to tell the browser to select automatically a margin, and it’s most commonly used to center an element in this way:

margin: 0 auto;

As said above, using 2 values applies the first to bottom & top, and the second to left & right.

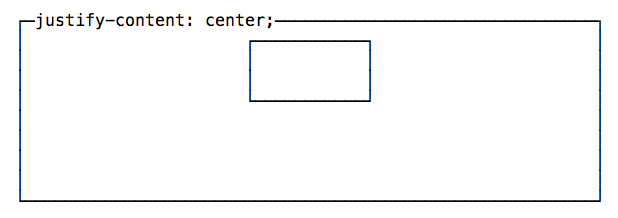

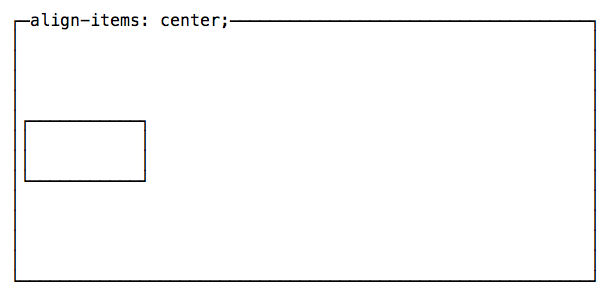

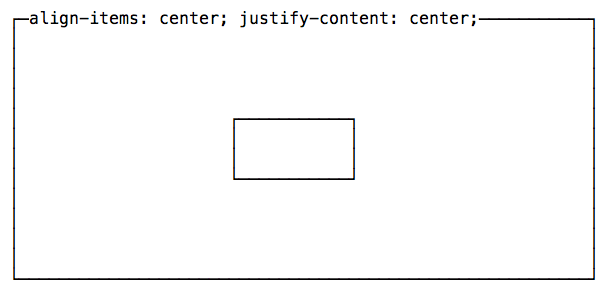

The modern way to center elements is to use Flexbox, and its justify-content: center; directive.

Older browsers of course do not implement Flexbox, and if you need to support them margin: 0 auto; is still a good choice.

Using a negative margin

margin is the only property related to sizing that can have a negative value. It’s extremely useful, too. Setting a negative top margin makes an element move over elements before it, and given enough negative value it will move out of the page.

A negative bottom margin moves up the elements after it.

A negative right margin makes the content of the element expand beyond its allowed content size.

A negative left margin moves the element left over the elements that precede it, and given enough negative value it will move out of the page.

BOX SIZING

The default behavior of browsers when calculating the width of an element is to apply the calculated width and height to the content area, without taking any of the padding, border and margin in consideration.

This approach has proven to be quite complicated to work with.

You can change this behavior by setting the box-sizing property.

The box-sizing property is a great help. It has 2 values:

border-boxcontent-box

content-box is the default, the one we had for ages before box-sizing became a thing.

border-box is the new and great thing we are looking for. If you set that on an element:

.my-div {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

width and height calculation include the padding and the border. Only the margin is left out, which is reasonable since in our mind we also typically see that as a separate thing: margin is outside of the box.

This property is a small change but has a big impact. CSS Tricks even declared an international box-sizing awareness day, just saying, and it’s recommended to apply it to every element on the page, out of the box, with this:

*, *:before, *:after {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

DISPLAY

The display property of an object determines how it is rendered by the browser.

It’s a very important property, and probably the one with the highest number of values you can use.

Those values include:

blockinlinenonecontentsflowflow-roottable(and all thetable-*ones)flexgridlist-iteminline-blockinline-tableinline-flexinline-gridinline-list-item

plus others you will not likely use, like ruby.

Choosing any of those will considerably alter the behavior of the browser with the element and its children.

In this section we’ll analyze the most important ones not covered elsewhere:

blockinlineinline-blocknone

We’ll see some of the others in later chapters, including coverage of table, flex and grid.

inline

Inline is the default display value for every element in CSS.

All the HTML tags are displayed inline out of the box except some elements like div, p and section, which are set as block by the user agent (the browser).

Inline elements don’t have any margin or padding applied.

Same for height and width.

You can add them, but the appearance in the page won’t change — they are calculated and applied automatically by the browser.

inline-block

Similar to inline, but with inline-block width and height applied as you specify.

block

As mentioned, normally elements are displayed inline, with the exception of some elements, including

divpsectionul

which are set as block by the browser.

With display: block, elements are stacked one after each other, vertically, and every element takes up 100% of the page.

The values assigned to the width and height properties are respected, if you set them, along with margin and padding.

none

Using display: none makes an element disappear. It’s still there in the HTML, but just not visible in the browser.

POSITIONING

Positioning is what makes us determine where elements appear on the screen, and how they appear.

You can move elements around, and position them exactly where you want.

In this section we’ll also see how things change on a page based on how elements with different position interact with each other.

We have one main CSS property: position.

It can have those 5 values:

staticrelativeabsolutefixedsticky

Static positioning

This is the default value for an element. Static positioned elements are displayed in the normal page flow.

Relative positioning

If you set position: relative on an element, you are now able to position it with an offset, using the properties

- top

- right

- bottom

- left

which are called offset properties. They accept a length value or a percentage.

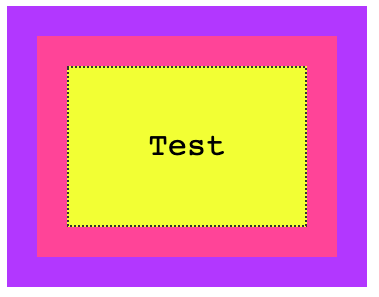

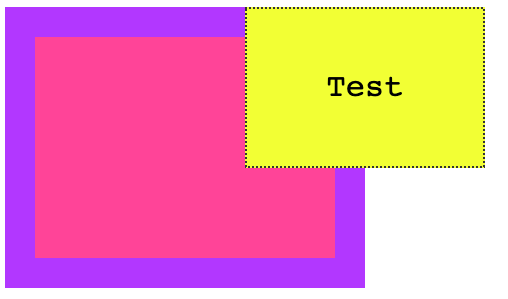

Take this example I made on Codepen. I create a parent container, a child container, and an inner box with some text:

<div class="parent">

<div class="child">

<div class="box">

<p>Test</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>

with some CSS to give some colors and padding, but does not affect positioning:

.parent {

background-color: #af47ff;

padding: 30px;

width: 300px;

}

.child {

background-color: #ff4797;

padding: 30px;

}

.box {

background-color: #f3ff47;

padding: 30px;

border: 2px solid #333;

border-style: dotted;

font-family: courier;

text-align: center;

font-size: 2rem;

}

here’s the result:

You can try and add any of the properties I mentioned before (top, right, bottom, left) to .box, and nothing will happen. The position is static.

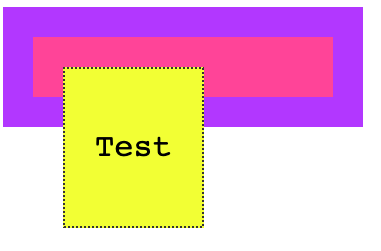

Now if we set position: relative to the box, at first apparently nothing changes. But the element is now able to move using the top, right, bottom, left properties, and now you can alter the position of it relatively to the element containing it.

For example:

.box {

/* ... */

position: relative;

top: -60px;

}

A negative value for top will make the box move up relatively to its container.

Or

.box {

/* ... */

position: relative;

top: -60px;

left: 180px;

}

Notice how the space that is occupied by the box remains preserved in the container, like it was still in its place.

Another property that will now work is z-index to alter the z-axis placement. We’ll talk about it later on.

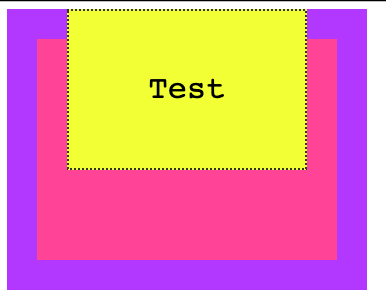

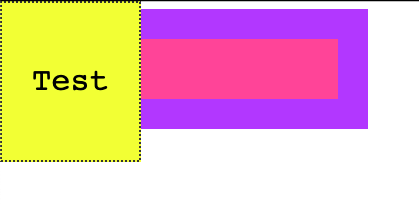

Absolute positioning

Setting position: absolute on an element will remove it from the document’s flow.

Remember in relative positioning that we noticed the space originally occupied by an element was preserved even if it was moved around?

With absolute positioning, as soon as we set position: absolute on .box, its original space is now collapsed, and only the origin (x, y coordinates) remain the same.

.box {

/* ... */

position: absolute;

}

We can now move the box around as we please, using the top, right, bottom, left properties:

.box {

/* ... */

position: absolute;

top: 0px;

left: 0px;

}

or

.box {

/* ... */

position: absolute;

top: 140px;

left: 50px;

}

The coordinates are relative to the closest container that is not static.

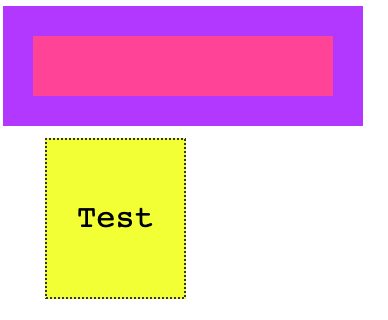

This means that if we add position: relative to the .child element, and we set top and left to 0, the box will not be positioned at the top left margin of the window, but rather it will be positioned at the 0, 0 coordinates of .child:

.child {

/* ... */

position: relative;

}

.box {

/* ... */

position: absolute;

top: 0px;

left: 0px;

}

Here’s how we already saw that .child is static (the default):

.child {

/* ... */

position: static;

}

.box {

/* ... */

position: absolute;

top: 0px;

left: 0px;

}

Like for relative positioning, you can use z-index to alter the z-axis placement.

Fixed positioning

Like with absolute positioning, when an element is assigned position: fixed it’s removed from the flow of the page.

The difference with absolute positioning is this: elements are now always positioned relative to the window, instead of the first non-static container.

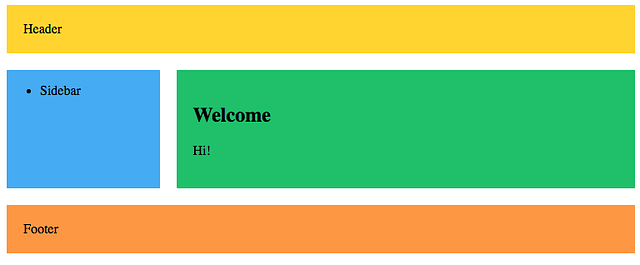

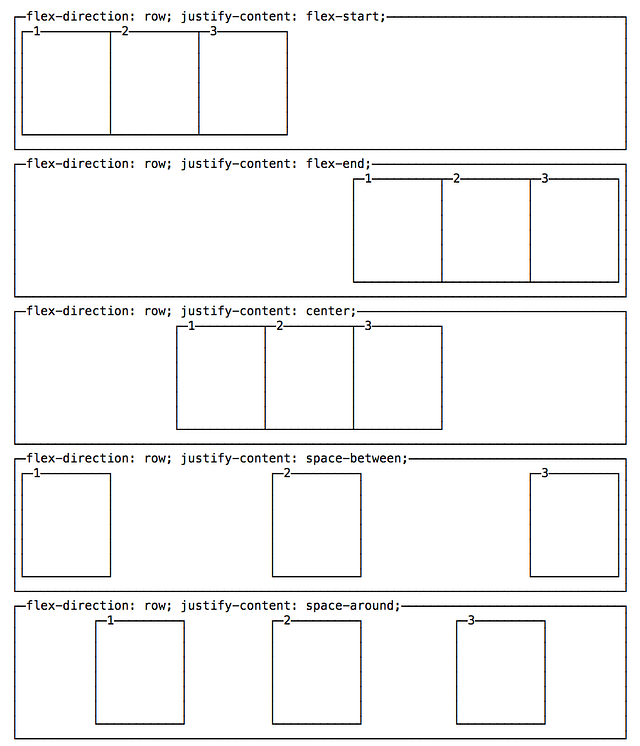

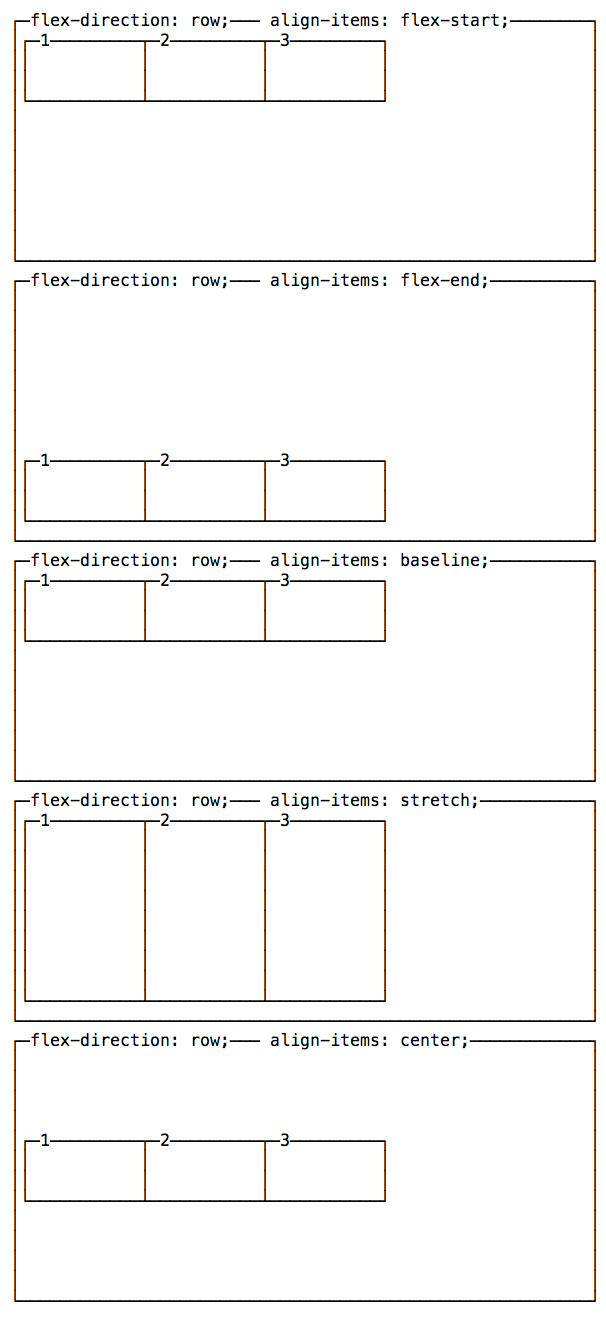

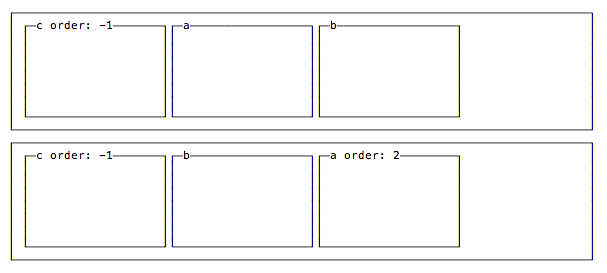

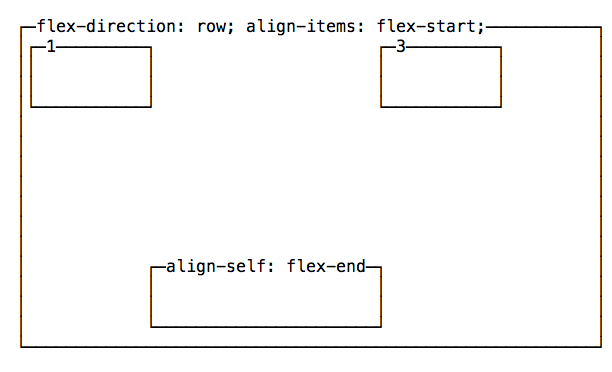

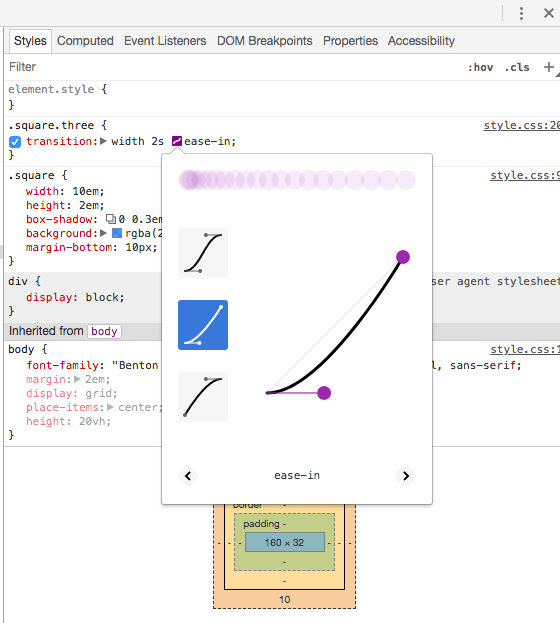

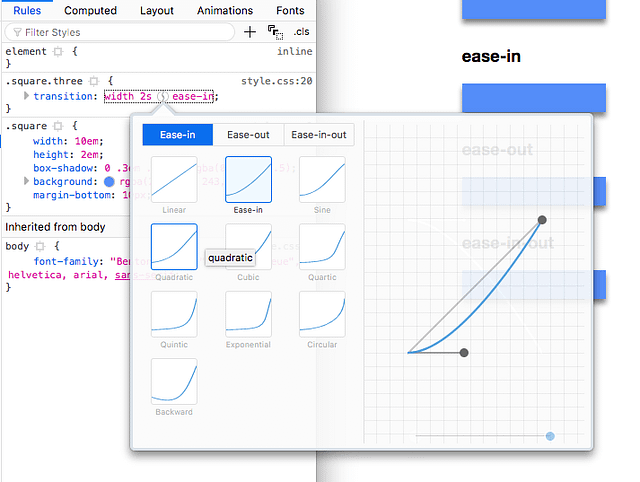

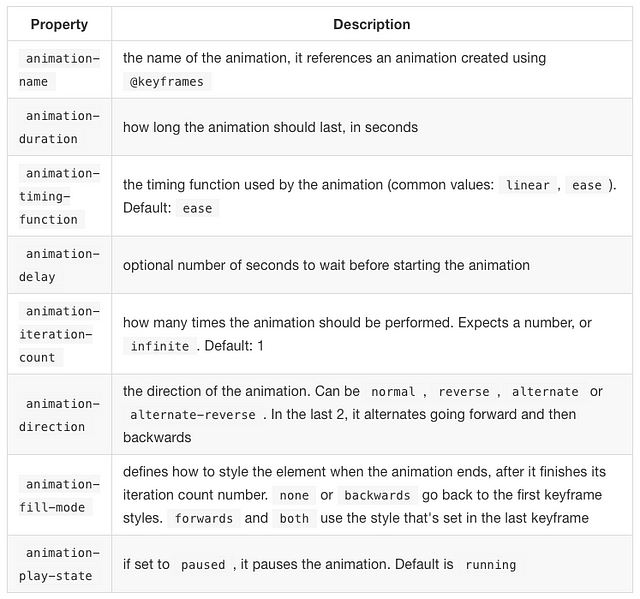

.box {