Software writing taught me that: a well written software is a simple software.

So I started to think how to achieve simplicity in a methodological

way. This is the first story of a series about this methodology.

Naturally it’s a snapshot because it’s in constant evolution.

Simplicity

A definition of simplicity is:

The quality or condition of being easy to understand or do.

Oxford dictionary (https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/simplicity)

So, a simple software is a software that is easy to understand.

After all software are written by humans for humans. This implies

that they should be understandable. Simplicity guarantees that its

understandability isn’t an intellectual pain.

A software solves a problem. So to build the former you should understand the latter.

But to build a simple software you should understand - clearly - a problem.

First step: architecture

On the Martin Fowler blog there is a deep definition of architecture and its explanation:

“Architecture is about the important stuff. Whatever that is.”

On first blush, that sounds trite, but I find it carries a lot of richness.

It means that the heart of thinking architecturally about software is to decide what is important, (i.e. what is architectural), and then expend energy on keeping those architectural elements in good condition.

Ultimately the important stuffs are about the solved problem. In other words about the software domain.

So we need an architecture that allows us to express - clearly - the software domain.

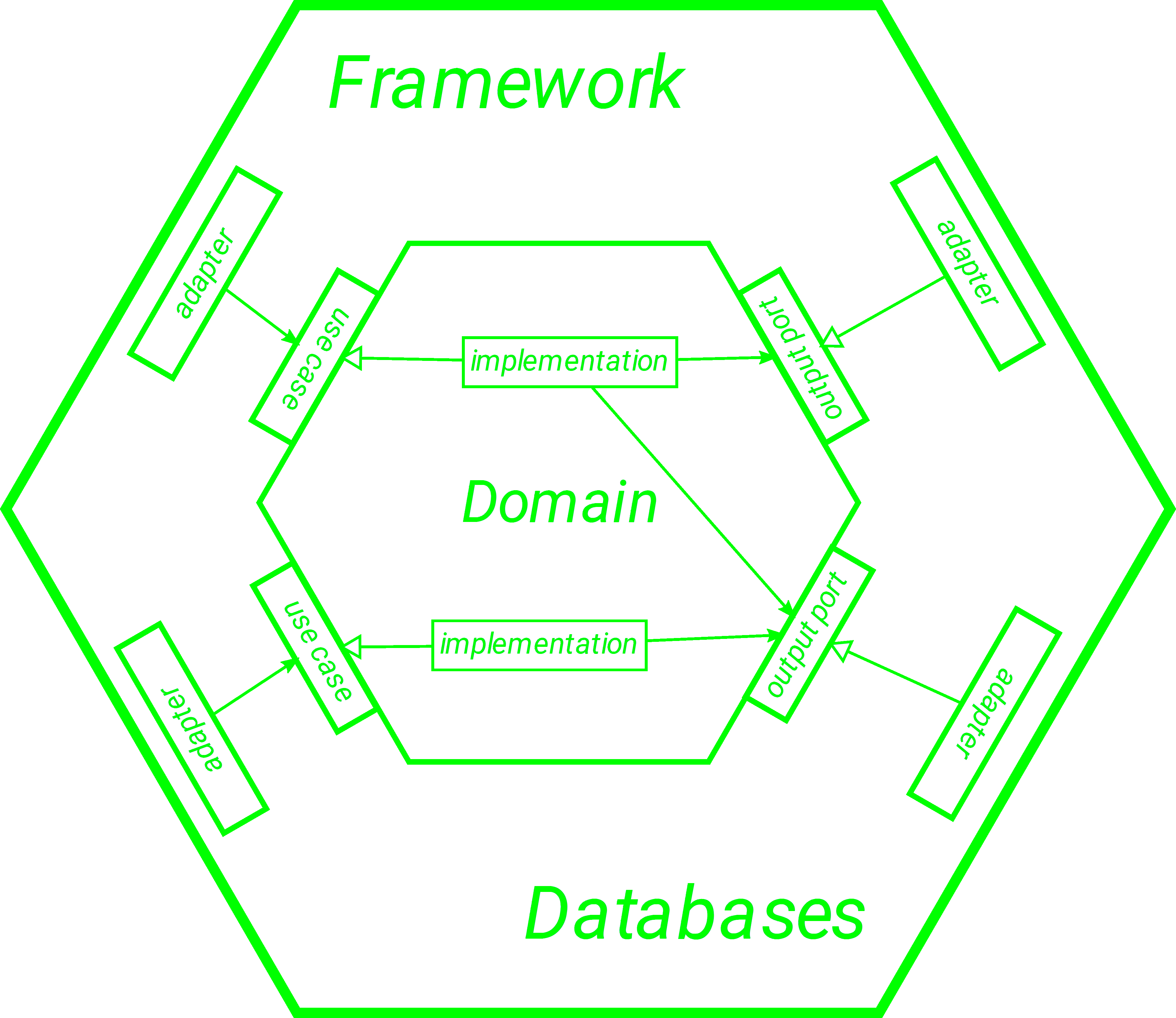

I think that the hexagonal architecture (a.k.a. ports and adapter architecture) is an ideal candidate.

It’s based on layered architecture, so the outer layer depends on the inner layer. Each layer is represented as a hexagon.

Here a UML-like diagram to express the below concepts:

In this architecture the innermost hexagon is dedicated to the

In this architecture the innermost hexagon is dedicated to the

software domain. Here we define domain objects and we express clearly:

- what the domain does as input port or use case (I prefer the latter because expressiveness).

- what the domain need, to fulfill use cases, as output port.

Conceptually on the sides of the domain layer there are use case and output port interfaces.

The communication between the outer layers and the domain layer happens through these interfaces.

The outer layer provides output port implementations and they use the use case interfaces.

The implementations and use case clients are are called adapter. Because they adapt our interface to a specific technology.

This relation is an instance of the dependency inversion principle. Simply put: high level concept, the domain, doesn’t rely on a specific

technology. Instead low level concept depends upon high level concept.

In other words our code is technology agnostic.

As you can see the concepts expressed in the outer layers are just details.

The real important stuff, the domain, is isolated and expressed clearly.

Code

A little project accompanies this series to show this methodology. It’s written in Java with the reactive paradigm from the beginning. For this reason the ReactiveX library is also used in the domain layer.

The software analyzes the capabilities (e.g. the java version, the

network speed and so on) of the machine and it exposes them through REST API.

It’s inspired by a real world software that I wrote because of work.

The first step is to define the innermost hexagon.

We can already identify:

- the main use case, expressed as GetCapabilitiesUseCase

- the object that describe the machine capabilities, expressed as Capabilities

The use case is an interface:

(if you never used ReactiveX: a Single means that the method will return asynchronously an object or an error)

public interface GetCapabilitiesUseCase {

Single<Capabilities> getCapabilities();

}

The Capabilities objects are immutable (precisely they’re value objects). And there is an associated builder (I’m using lombok annotations to generate the code):

@RequiredArgsConstructor

@Value

@Builder

public class Capabilities {

private final String javaVersion;

private final Long networkSpeed;

}

#architecture #software-architecture #programming #java #hexagonal-architecture #reactive-programming #software-development #software-engineering

![Road to Simplicity: Hexagonal Architecture [Part One]](https://firebasestorage.googleapis.com/v0/b/hackernoon-app.appspot.com/o/images%2FoIZ6zbypp5XdOfvNWimTAhHLpGC2-iy8u13p8.jpeg?alt=media&token=9b166fb9-fdb1-4ff9-afa5-85362f0b0dcd)