A web application or a website revolves around the request-response cycle and Django applications are no exception to this. But it is not just a two step process. Our Django applications needs to go through various stages to return the end user some result. To understand the Django framework better we must understand how the requests are initiated and the end result is served to the end user. In the following sections I am going to explain various stages of requests and the software or code used there.

When setting up a new Django project, one of the first things you’ll do is wire up your URLconfs and set up some views. But what’s actually happening under the hood here? How does Django route traffic to the view, and what part do middlewares play in this cycle?

WSGI

As we know a Web server is a program that uses HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) to serve the files that form Web pages to users, in response to their requests, which are forwarded by their computers’ HTTPclients.

WSGI is a tool created to solve a basic problem: connecting a web server to a web framework. WSGI has two sides: the ‘server’ side and the ‘application’ side. To handle a WSGI response, the server executes the application and provides a callback function to the application side. The application processes the request and returns the response to the server using the provided callback. Essentially, the WSGI handler acts as the gatekeeper between your web server (Apache, NGINX, etc) and your Django project.

Between the server and the application lie the middlewares. You can think of middlewares as a series of bidirectional filters: they can alter (or short-circuit) the data flowing back and forth between the network and your Django application.

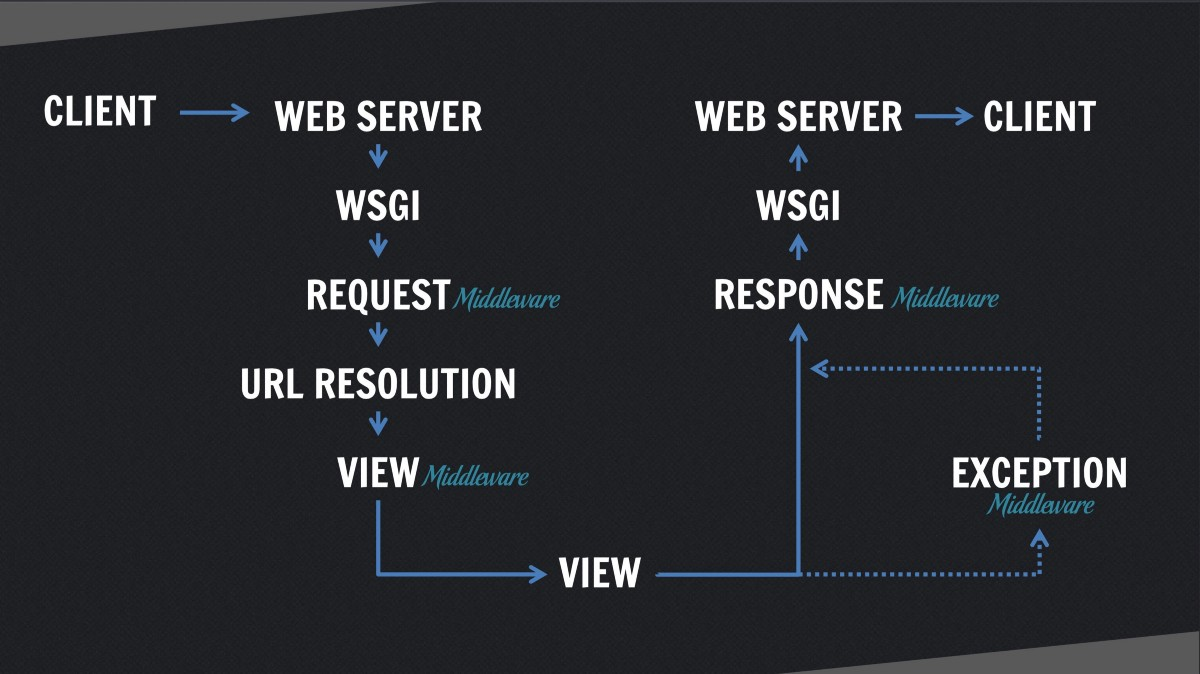

The Big Picture — Data Flow

When the user makes a request of your application, a WSGI handler is instantiated, which:

- imports your

settings.pyfile and Django’s exception classes. - loads all the middleware classes it finds in the

MIDDLEWARE_CLASSESorMIDDLEWARES(depending on Django version) tuple located insettings.py - builds four lists of methods which handle processing of request, view, response, and exception.

- loops through the request methods, running them in order

- resolves the requested URL

- loops through each of the view processing methods

- calls the view function (usually rendering a template)

- processes any exception methods

- loops through each of the response methods, (from the inside out, reverse order from request middlewares)

- finally builds a return value and calls the callback function to the web server

Let’s get started.

Layers of Django Application

- Request Middlewares

- URL Router(URL Dispatcher)

- Views

- Context Processors

- Template Renderers

- Response Middlewares

Whenever the request comes in it is handled by the Request middlewares. We can have multiple middlewares. we can find it in project settings(settings.py). Django request middlewares follows the order while processing the request. Suppose if we have request middlewares in the order A, B, C then the request first processed by the middleware A and then B and then C. Django comes up with bunch of default middlewares. We can also write our own or custom middlewares. After request processed by the middlewares it will be submitted to the URL Router or URL dispatcher.

URL Router will take the request from the request middleware and it takes the URL Path from the request. Based on the url path URL router will tries to match the request path with the available URL patterns. These URL patterns are in the form of regular expressions. After matching the URL path with available URL patterns the request will be submitted to the View which is associated with the URL.

Now, we are in business logic layer Views. Views processes the business logic using request and request data(data sent in GET, POST, etc). After processing the request in the view the request is sent context processors, by using the request context processors adds the context data that will help Template Renderers to render the template to generate the HTTP response.

Again the request will send back to the Response middlewares to process it. Response middlewares will process the request and adds or modifies the header information/body information before sending it back to the client(Browser). After the browser will process and display it to the end user.

Middlewares

Middlewares are employed in a number of key pieces of functionality in a Django project: for example :~ we use CSRF middlewares to prevent cross-site request forgery attacks. They’re used to handle session data. Authentication and authorization is accomplished with the use of middlewares. We can write our own middleware classes to shape (or short-circuit) the flow of data through your application.

process_request

Django middlewares must have at least one of the following methods: process_request, process_response, process_view, and process_exception. These are the methods which will be collected by the WSGI Handler and then called in the order they are listed. Let’s take a quick look at django.contrib.auth.middleware.AuthenticationMiddleware, one of the middlewares which are installed by default when you run django-admin.py startproject:

def get_user(request):if not hasattr(request, '_cached_user'): request._cached_user = auth.get_user(request) return request._cached_userclass AuthenticationMiddleware(MiddlewareMixin):

def process_request(self, request): assert hasattr(request, 'session'), ( "The Django authentication middleware requires session middleware""to be installed. Edit your MIDDLEWARE%s setting to insert "

"‘django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware’ before "

“‘django.contrib.auth.middleware.AuthenticationMiddleware’.”) % ("_CLASSES" if settings.MIDDLEWARE is None else "") request.user = SimpleLazyObject(lambda: get_user(request))

As you can see, this middleware only works on the ‘request’ step of the data flow to and from your Django application. This middleware first verifies that the session middleware is in use and has been called already, then it sets the userby calling the get_user helper function. As the WSGI Handler iterates through the list of process_requestmethods, it’s building up this requestobject which will eventually be passed into the view, and you’ll be able to reference request.user. Some of the middlewares in settings.py won’t have process_requestmethods. No big deal; those just get skipped during this stage.

process_requestshould either return None (as in this example), or alternately it can return an HttpResponseobject. In the former case, the WSGI Handler will continue processing the process_request methods, the latter will “short-circuit” the process and begin the process_response cycle.

Resolve the URL

Now that the process_request methods have each been called, we now have a request object which will be passed to the view. Before that can happen, Django must resolve the URL and determine which view function to call. This is simply done by regular expression matching. Your settings.pywill have a key called ROOT_URLCONF which indicates the ‘root’ urls.py file, from which you’ll include the urls.py files for each of your apps. URL routing is covered pretty extensively in the Django tutorials so there’s no need to go into it here.

A view has three requirements:

- It must be callable. It can be a function-based view, or a class-based view which inherits from

Viewtheas_view()method to make it callable depending on the HTTP verb (GET, POST, etc) - It must accept an

HttpRequestobject as the first positional argument. This is the result of calling all theprocess_requestandprocess_viewmiddleware methods. - It must return an

HttpResponseobject, or raise an exception. It’s this response object which is used to kick off the WSGI Handler’sprocess_viewcycle.

process_view

Now that the WSGI Handler knows which view function to call, it once again loops through its list of middleware methods. The process_view method for any Django middleware is declared like this:

process_view(request, view_function, view_args, view_kwargs)

Just like with process_request, the process_view function must return either None or an HttpResponse object (or raise an exception), allowing the WSGI Handler to either continue processing views, or “short-circuiting” and returning a response. Take a look at the source code for CSRF Middleware to see an example of process_view in action. If a CSRF cookie is present, the process_view method returns None and the execution of the view occurs. If not, the request is rejected and the process is short-circuited, resulting in a failure message.

process_exception

If the view function raises an exception, the Handler will loop through its list of process_exception methods. These methods are executed in reverse order, from the last middleware listed in settings.py to the first. If an exception is raised, the process will short-circuit and no other process_exceptionmiddlewares will be called. Usually we rely on the exception handlers provided by Django’s BaseHandler, but you can certainly implement your own exception handling when you write your own custom middleware class.

process_response

At this point, we’ll have an HttpResponse object, either returned by the view or by the list of process_view methods built by the WSGI handler, and it’s time to loop through the response middlewares in turn. This is the last chance any middleware has to modify the data, and it’s executed from the inner layer outward (think of an onion, with the view at the center). Take a look at the cache middleware source code for an example of process_response in action: depending on different conditions in your app (i.e. whether caching is turned off, if we’re dealing with a stream, etc), we’ll want the response stored in the cache or not.

Note: One difference between pre-1.10 Django and later versions: in the older style MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES, every middleware will always have its process_response method called, even if an earlier middleware short-circuited the process. In the new MIDDLEWARES style, only that middleware and the ones which executed before it will have their process_response methods called. Consult the documentation for more details on the differences between MIDDLEWARES and MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES.

All Done!

Finally, Django’s WSGI Handler builds a return value from the HttpResponseobject and executes the callback function to send that data to the web server and out to the user.

So, two key takeaways:

- Now we know how the view function is matched to a URLconf and what actually calls it (the WSGI Handler).

- There are four key points you can hook into the request/response cycle through your own custom middleware:

process_request’,process_response,process_view, andprocess_exception. Think of an onion: request middlewares are executed from the outside-in, hit the view at the center, and return through response middlewares back to the surface.

Originally published by Sarthak Kumar at https://medium.com

Learn More

☞ Python and Django Full Stack Web Developer Bootcamp

☞ Django 2 & Python | The Ultimate Web Development Bootcamp

☞ The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide to Django 1.11

☞ Django Core | A Reference Guide to Core Django Concepts

#django