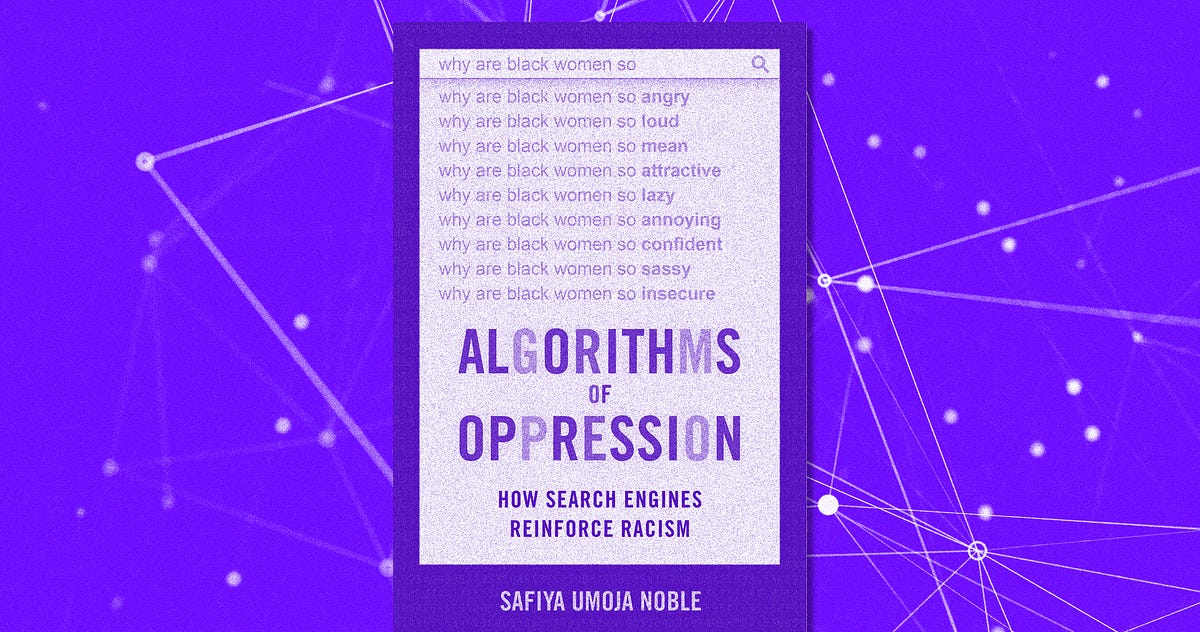

When Algorithms of Oppression was published in 2018, it was a landmark work that interrogated the racism encoded into popular technology products like Google’s search engine. Given that many Americans are currently using Google search to try to understand racism after the national uprising sparked by the murder of George Floyd, it’s a good time to remember the architecture they are using to do so is itself deeply compromised — and how that came to pass. This excerpt, from Safiya Umoja Noble’s enduring work, explains why anti-Black racism appears, and endures, in tech products we are told to view as neutral.

On June 28, 2016, Black feminist and mainstream social media erupted over the announcement that Black Girls Code, an organization dedicated to teaching and mentoring African American girls interested in computer programming, would be moving into Google’s New York offices. The partnership was part of Google’s effort to spend $150 million on diversity programs that could create a pipeline of talent into Silicon Valley and the tech industries. But just two years before, searching the phrase “black girls” surfaced “Black Booty on the Beach” and “Sugary Black Pussy” to the first page of Google results, out of the trillions of web-indexed pages that Google Search crawls.

In part, the intervention of teaching computer code to African American girls through projects such as Black Girls Code is designed to ensure fuller participation in the design of software and to remedy persistent exclusion. The logic of new pipeline investments in youth was touted as an opportunity to foster an empowered vision for Black women’s participation in Silicon Valley industries. Discourses of creativity, cultural context, and freedom are fundamental narratives that drive the coding gap, or the new coding divide, of the 21st century.

Neoliberalism has emerged and served as a framework for developing social and economic policy in the interest of elites, while simultaneously crafting a new worldview: an ideology of individual freedoms that foreground personal creativity, contribution, and participation, as if these engagements are not interconnected to broader labor practices of systemic and structural exclusion. In the case of Google’s history of racist bias in search, no linkages are made between Black Girls Code and remedies to the company’s current employment practices and product designs. Indeed, the notion that lack of participation by African Americans in Silicon Valley is framed as a “pipeline issue” posits the lack of hiring Black people as a matter of people unprepared to participate, despite evidence to the contrary.

Google, Facebook, and other technology giants have been called to task for this failed logic. Laura Weidman Powers, of CODE2040, stated in an interview with Jessica Guynn at USA Today, “This narrative that nothing can be done today and so we must invest in the youth of tomorrow ignores the talents and achievements of the thousands of people in tech from underrepresented backgrounds and renders them invisible.” Blacks and Latinos are underemployed despite the increasing numbers graduating from college with degrees in computer science.

Filling the pipeline and holding “future” Black women programmers responsible for solving the problems of racist exclusion and misrepresentation in Silicon Valley or in biased product development is not the answer. Commercial search prioritizes results predicated on a variety of factors that are anything but objective or value-free. Indeed, there are infinite possibilities for other ways of designing access to knowledge and information, but the lack of attention to the kind of White and Asian male dominance that Guynn reported sidesteps those who are responsible for these companies’ current technology designers and their troublesome products.

Framing the problems as “pipeline” issues instead of as an issue of racism and sexism, which extends from employment practices to product design. “Black girls need to learn how to code” is an excuse for not addressing the persistent marginalization of Black women in Silicon Valley.

Who is responsible for the results?

As a result of the lack of African Americans and people with deeper knowledge of the sordid history of racism and sexism working in Silicon Valley, products are designed with a lack of careful analysis about their potential impact on a diverse array of people. If Google software engineers are not responsible for the design of their algorithms, then who is?

These are the details of what a search for “black girls” would yield for many years, despite that the words “porn,” “pornography,” or “sex” were not included in the search box. In the text for the first page of results, for example, the word “pussy,” as a noun, is used four times to describe Black girls. Other words in the lines of text on the first page include “sugary” (two times), “hairy” (one), “sex” (one), “booty/ass” (two), “teen” (one), “big” (one), “porn star” (one), “hot” (one), “hardcore” (one), “action” (one), “galeries [sic]” (one).

In the case of the first page of results on “black girls,” I clicked on the link for both the top search result (unpaid) and the first paid result, which is reflected in the right-hand sidebar, where advertisers that are willing and able to spend money through Google AdWords have their content appear in relationship to these search queries.

All advertising in relationship to Black girls for many years has been hypersexualized and pornographic, even if it purports to be just about dating or social in nature. Additionally, some of the results such as the U.K. rock band Black Girls lack any relationship to Black women and girls. This is an interesting co-optation of identity, and because of the band’s fan following as well as possible search engine optimization strategies, the band is able to find strong placement for its fan site on the front page of the Google search.

Published text on the web can have a plethora of meanings, so in my analysis of all of these results, I have focused on the implicit and explicit messages about Black women and girls in both the texts of results or hits and the paid ads that accompany them. By comparing these to broader social narratives about Black women and girls in dominant U.S. popular culture, we can see the ways in which search engine technology replicates and instantiates these notions.

#google #racism #women #algorithms #technology #algorithms