Authentication in SPA (ReactJS and VueJS)

Authentication in a single page application (SPA) involves several patterns with pros and cons. This article will list the main important concepts to know and have in mind when dealing with user authentication, especially in this common architecture:

Security prerequisites

Encrypted communication (httpS)

- As authentication uses HTTP headers and exchange high sensitive data (password, access token, …), the communication must be encrypted otherwise someone sniffing the network may be able to grab them.

Do not use URL query parameters to exchange sensitive data

- URL and URL query parameters may end up in the server log, browser logs, browser history: someone could grab the data from there and try to re-use it.

- Un-trained users may copy and paste a URL with authentication tokens, which could lead to basically unintended session-hijacking.

- You may run into URL size limitations on browsers or servers

Prevent brute-force attacks

- An attacker may try to infer password, token or username by trying a lot of possibilities

- Rate limiter should be implemented on your backend server to limit the number of tries and retries.

- Ban or tarpit users that hit too many server errors (300+, 400+, 500)

- Do not give clues about your technologies, for instance, clear the

X-Powered-Bythat says what kind of server you use in the response header. You may use Helmetjs if you are operating ExpressJS.

Update your dependencies on a regular basis

- To avoid using packages with security issues update your NPM packages:

# List security breaches

npm audit

# Upgrade of minor and patch version following your version ranges in package.json

yarn outdated

yarn update

# Interactive upgrade of minor and patch version following your version ranges in package.json

yarn upgrade-interactive

# List outdated dependencies including major version

yarn upgrade-interactive --latest

# Same with npm

npm outdated

npm update

# Tool for upgrading to major versions (with potential breaking changes)

npm install -g npm-check-updates

ncu

- Also, keep your server up to date if you are not using a PaaS.

Add monitoring

- Monitor your servers to identify abnormal patterns before the incident.

Authentication

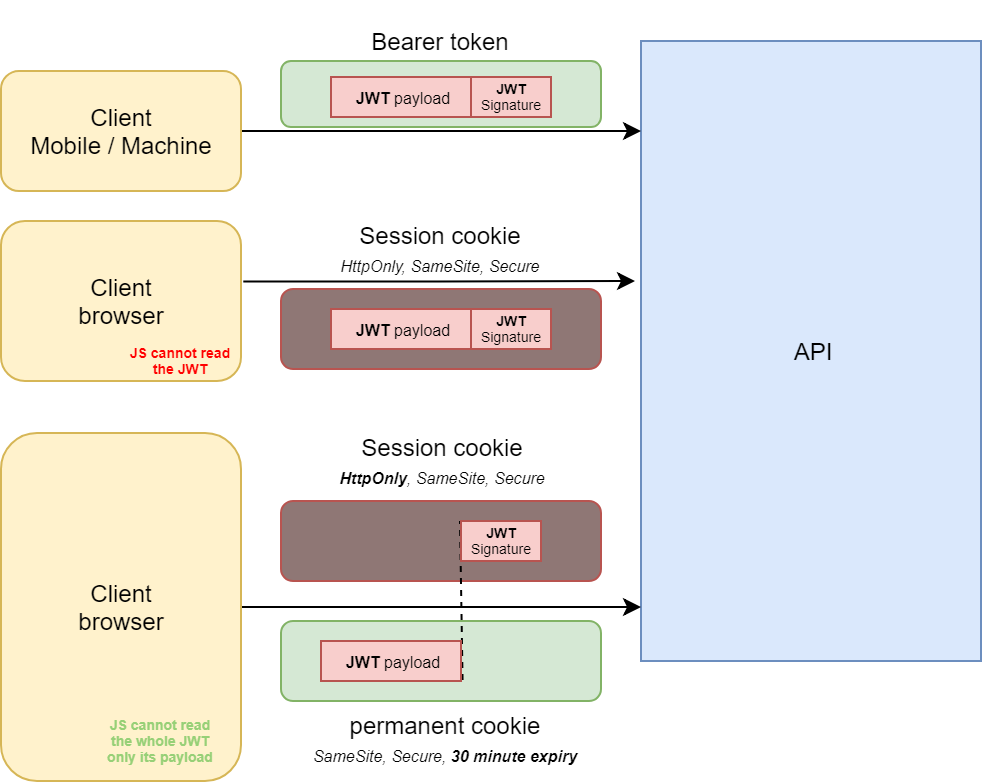

There are 2 main authentication mechanisms (you will see later that we can combine them) to identify a client on a REST API:

- Bearer Token

- Authentication cookie

Bearer Token

What is a bearer token?

A bearer token is a value that goes into the Authorization header of any HTTP requests. It is not automatically stored anywhere, it has no expiry date and no associated domain. It’s just a value:

GET https://www.example.com/api/users

Authorization: Bearer my_bearer_token_value

To have a stateless application, we can use JWT for our token format. Basically, a JWT contains 3 parts:

- Header

- Payload (it can hold the user id and the roles of the user) + an expiration time (optional)

- Signature

JWT is a cryptographically secure means of exchanging information that make stateless authentication possible. The signature certifies that the payload has not been modified (i.e. that is not compromised) thanks to symmetric or asymmetric (RSA) signature. The header contains the format and public key address to verify the signature (for asymmetric).

Basically, the client application gets a JWT token once authenticated by a user/password authentication (or other means).

He sends all the following requests to the server with the JWT token in the HTTP header thanks to JAVASCRIPT. The server verifies whether the signature corresponds to the payload, if there is a match, it can trust the content of the payload.

Basic use cases

- Protecting traffic between a browser and a specific back end

- Protecting traffic between a mobile application, desktop application and a specific back end

- Protecting traffic between backends (M2M) controlled by different parties (OpenId Connect is an example), or within back end services of one party

Where to store JWT?

We have to manually store the JWT in the clients (memory, local/session cookie, local storage, etc…).

It is not recommended to store the JWT in the browser local storage:

- It will remain if the user closes the browser so the session can be restored until the JWT expires.

- Any JavaScript code on your page can access local storage: it has no data protection whatsoever.

- It can’t be used by web workers

Storing JWT in session cookie may be the solution, we will talk about that later.

To go further: https://auth0.com/docs/security/store-tokens

Basic attacks

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks are the most common when javascript is dealing with security: the attacker may compromise a web site JS dependencies or use user input to add malicious javascript code to steal a victim’s JWT. The attacker would then use it to impersonate the user.

- For instance, on a blog comment, a user may add JS in his comment to do client-side JS on the page:

<img src=x onerror="javascript:alert('XSS')">

XSS attacks can be mitigated by escaping and controlling user-generated content but it will be very difficult to detect and mitigate a compromised web dependency served by a public CDN.

Authentication cookie

A cookie is a name-value pair, that is stored in a web browser, and that has an expiry date and associated domain. Cookies are stored in the web browser. They can be created by client browser JavaScript:

document.cookie = ‘my_cookie_name=my_cookie_value’ // JavaScript

or from the server using an HTTP Response header:

Set-Cookie: my_cookie_name=my_cookie_value // HTTP Response Header

The web browser automatically sends cookies with every request to the cookie’s domain.

GET https://www.example.com/api/users

Cookie: my_cookie_name=my_cookie_value

In most (stateful) use cases, a cookie is used to store a session ID. The session ID is managed by the server (creation and timeout). We talk about stateful as the server needs to manage a state on the server whereas a JWT token is stateless.

There are 2 kinds of cookies (source):

- Session cookies: The cookie is deleted when the client shuts down because it doesn’t specify an Expires or Max-Age directive. However, web browsers may use session restoring, which makes most session cookies permanent, as if the browser was never closed. The session timeout must be handled on the server side.

- Permanent cookies

Instead of expiring when the client closes, permanent cookies expire at a specific date (Expires) or after a specific length of time (Max-Age).

Server cookies can be configured with several options:

- HttpOnly cookies**:** Browser javascript cannot read them.

- Secure cookie: the browser includes the cookie in an HTTP request only if the request is transmitted over a secure channel (typically HTTPS).

- SameSite cookies let servers require that a cookie shouldn’t be sent with cross-site requests, which somewhat protects against cross-site request forgery attacks (CSRF). SameSite cookies are still experimental and are not supported by all browsers yet.

Basic use cases

- Protecting traffic between a browser and a specific back end

- Cookies make it more difficult for non-browser based applications (like mobile or tablet apps) to consume your API.

Where to store cookies?

They are automatically stored in the web browser with an expiry date (optional) and associated domain.

Basic attacks

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) if the cookies are not created with HttpOnly option: an attacker could inject Javascript code that would steal a victim’s authentication cookie.

- Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is a common attack with authentication cookies. CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) configuration can be done on the server side to authorize only specific hostnames. However, CORS is checked on the client side by the browser. Even worst, the same origin policy given by CORS is applicable only for browser-side programming languages. So if you try to post to a different server than the origin server using JavaScript, then the same origin policy comes into play but if you post directly from an HTML form, the action can point to a different server like:

<form action="http://someotherserver.com">

as there is no javascript involved in posting the form, the same origin policy is not applicable and the browser is sending the cookies along with the form data.

Another example of CSRF: let’s assume that the user, while he is still logged in to facebook.com, visits a page on bad.com. Now, bad.com belongs to an attacker where he has coded the following on bad.com:

<img src="https://facebook.com/postComment?userId=dupont_123&comment=I_VE_BEEN_HACKED>

To mitigate XSS, the HttpOnly option must be set on the cookie.

To mitigate CSRF, the SameSite option must be set on the cookie. The SameSite option is not supported by all browsers so it will not prevent all CSRF attacks. Some other mitigation strategies (that can be combined) can be used:

- Short session timeout (in financial domains the timeout is about 10 minutes or less)

- Critical actions should always ask for user credentials (for instance, asks for the user password in the form that changes the user email address)

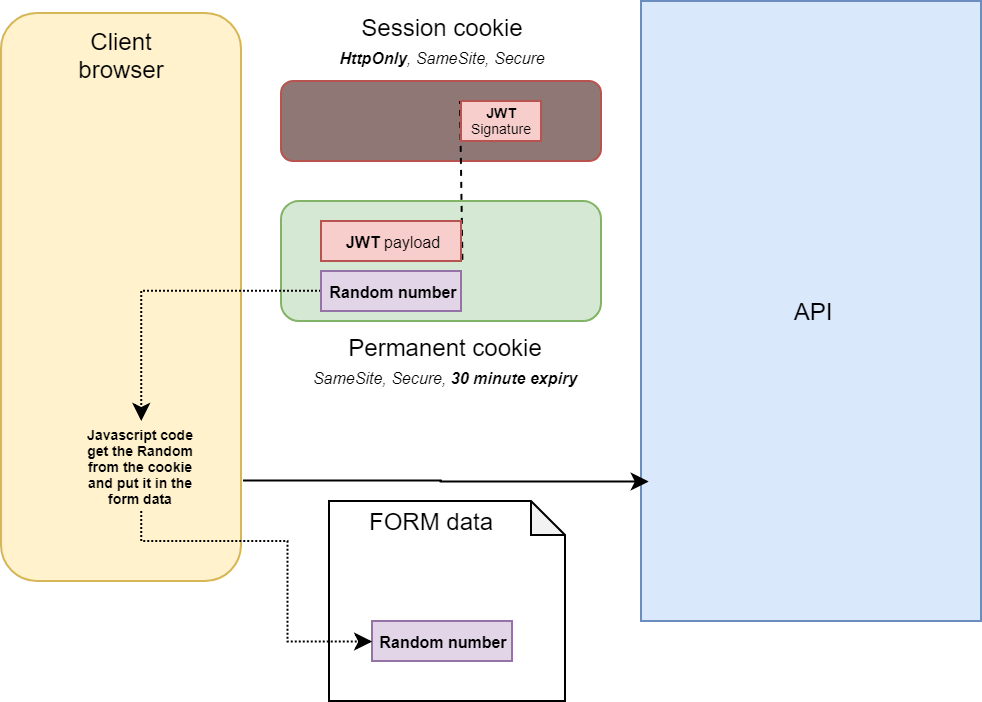

- Double submitted cookies: when a user visits a site, the site should generate a (cryptographically strong) pseudorandom value and set it as a cookie (without httpOnly flag to let it available from JS) on the user’s machine in addition to an httpOnly authentication cookie. The site should require every form submission to include this pseudorandom value as a form value and also as a cookie value. When a POST request is sent to the site, the request should only be considered valid if the form value and the cookie value are the same. When an attacker submits a form on behalf of a user, he can only modify the values of the form. An attacker cannot read any data sent from the server or modify cookie values, per the same-origin policy. This means that while an attacker can send any value he wants with the form, he will be unable to modify or read the value stored in the cookie. Since the cookie value and the form value must be the same, the attacker will be unable to successfully submit a form unless he is able to guess the pseudorandom value (source) or steal the value from a concomitant XSS attack.

Can we combine both?

Let’s summarize what we are looking for our authentication mechanism on our server API:

- Support browser and M2M calls

- XSS and CSRF resistant as much as possible

- Stateless if possible

What about putting a JWT inside a cookie to get the best of both worlds?

Our API should support JWT bearer token from the request header as well as JWT inside a session cookie. If we want to authorize the javascript to read the JWT payload we can use a two cookie authentication approach by combining 2 types of cookies so that the XSS attack surface is limited.

The two cookie authentication approach has been described by Peter Locke in https://medium.com/lightrail/getting-token-authentication-right-in-a-stateless-single-page-application-57d0c6474e3

JWT can be updated on each request seamlessly by the server as the new one will be in the cookie response and automatically stored by the browser. This way, the expiration date of the JWT can be put back.

To limit CSRF, mutations should never be done using a GET query, use PUT or POST. Mutations with high-security concerns should ask user credentials again, for instance, the change email mutation should ask the user password to validate the change. The temporary cookie could also embed a random number that is read by JS and submit in a hidden form field as long with the form data. The server has to check if the random number in the cookie matches the value from the form data.

Wrap up

The authentication flow for our SPA is now the following:

- STEP 1: Our SPA application checks if a cookie with the JWT payload exists, if yes, the user has authenticated otherwise the SPA redirect to the /login page. If you are using a single httpOnly cookie, the SPA should make an API call, for instance, //backend/api/me to know who is the current user and get an unauthorized error if the authentication cookie (containing the JWT) is missing or invalid.

- STEP 2 — Option 1: the /login page on the front end asks for user credentials (login/password) and then posts them on the backend API using an AJAX request. The AJAX response will set the authentication cookie with a JWT inside.

- STEP 2 — Option 2: the /login page provides an OpenID authentication using an OAuth flow. For an authorization code grant flow, the /login should redirect the whole browser window to //backend/auth/. The OAuth flow should be done and the backend should set the authentication cookie with a JWT inside in the last response. It will then redirect the browser to the front end. The SPA will then start again, so go the STEP 1 again.

Feel free to comment and put your thought on this post. If you like what you read, don’t forget to clap!

Recommended Reading

ASP.NET CORE Token Authentication and Authorization using JWT

In-depth Fullstack JWT Authentication Tutorial

Build a Mobile Phone Authentication Component with React and Firebase

#reactjs #vue-js