For quite some time, git had been this nebulous, terrifying, thing for me. It was kind of like walking on a tight rope holding a bunch of fine china. Yeah I knew how to git add, git commit, and git push. But if I had to do anything outside of that, I’d quickly lose my balance, drop the fine china, and git would inevitable break my project into unrecognizable pieces.

If you’re a developer, you probably know git pretty well. But git is now becoming an inescapable skill for anyone in a field involving programming and collaboration, especially data science.

So I finally bit the proverbial bullet and tried to understand the more holistic picture of git and what its commands were doing with my code. Fortunately, it turned out to be something that wasn’t as complicated as I had thought and by correcting my underlying mental model of it, I had more confidence and less anxiety when tackling new projects.

The four areas of git

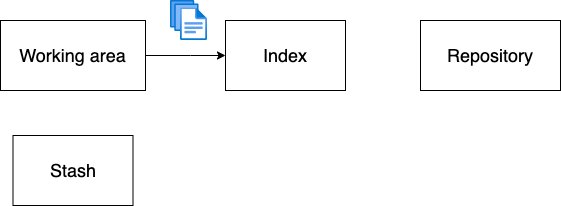

There are four areas in git: stash, working area, index, and repository.

Your typical git workflow works from left to right, starting at the working area. When you make any changes to files in a git repository, these changes show in the working area. To view which files were changed along with new files you created, simply do a git status. To show the more granular details about what exactly was changed in a file, just do a git diff [file name].

Once you’re satisfied with your changes, you then add the changed files from the working area to the index with a git add command.

The index functions as a sort of staging area. It exists because you might be trying some things out and changing a lot of code in the working area but you don’t necessarily want all those changes to be in the repository area just yet.

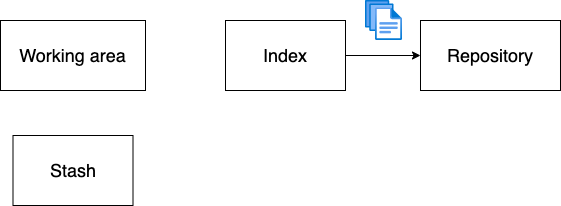

So the idea is to just selectively add the changes you want to the index and it’s best practice for the changes you add to be some logical unit or collection of things that are related. For example, you might decide to add all the files with changes that relate to the new preprocessing function you wrote in Python.

Once you’ve added all relevant files to the index, finally move them to the repository by doing a git commit -m 'Explanation of my changes'. You should see that there are no difference between the index and repository now - something you can verify with a git diff --cached.

Mistakes were made

But life is not so ideal. Eventually you’ll make a commit with an inappropriate message that you want to change, or you’ll decide that all those new things you added totally broke everything and now you want to go back to how it was before. Ever wanted to include a coworker’s updates into the code you’re working on only to find there are file conflicts?

You might have seen some git commands like rebase, reset, and revert. If these commands scare you, you’re not alone. Some of them are powerful, and can destroy your project if you don’t know how to use them. But fret not, you’re about to learn how to use them. 😊

#data-science #git #developer #github #programming