Turn Python Scripts into Beautiful Machine Learning Tools

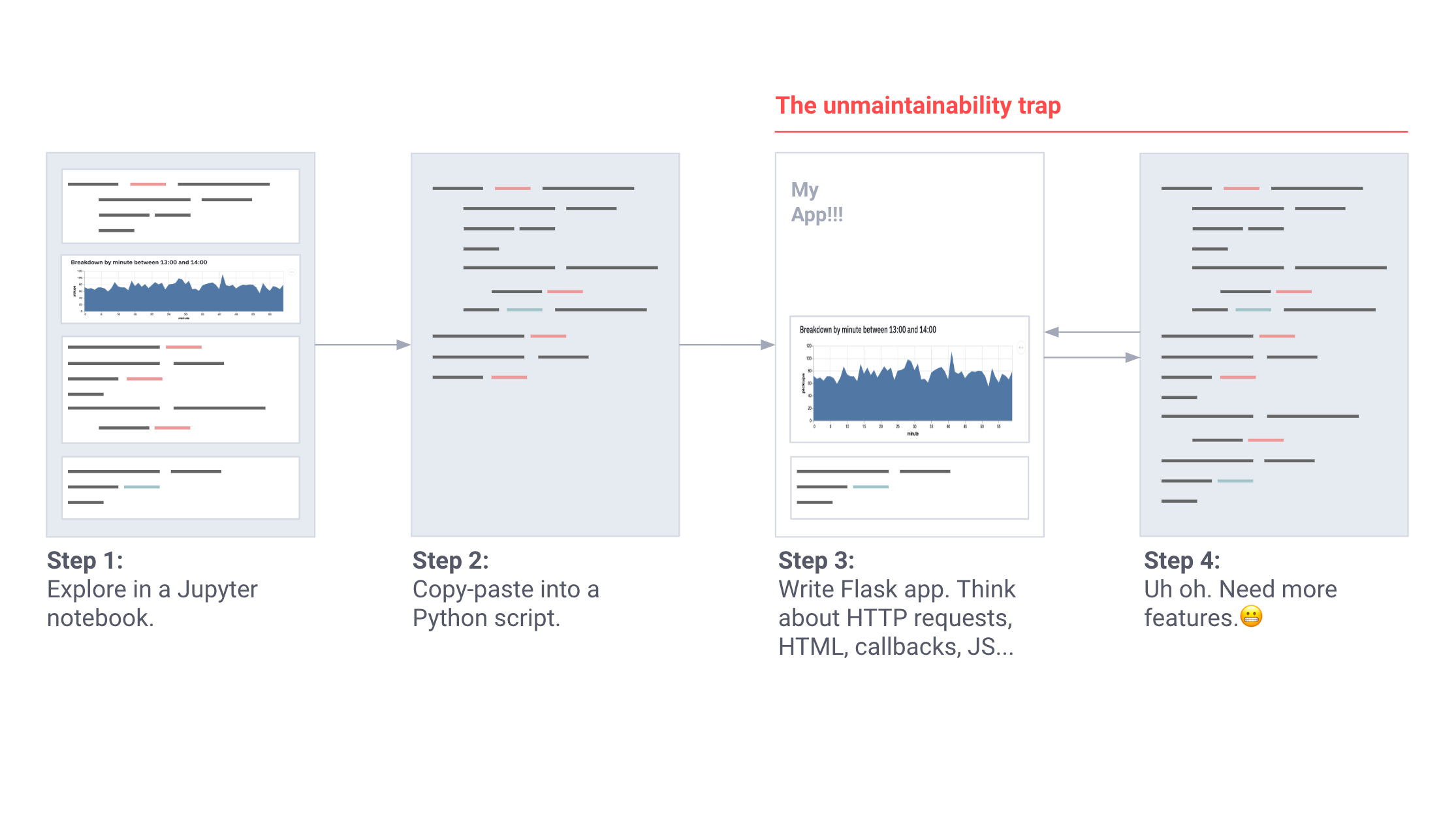

In my experience, every nontrivial machine learning project is eventually stitched together with bug-ridden and unmaintainable internal tools. These tools — often a patchwork of Jupyter Notebooks and Flask apps — are difficult to deploy, require reasoning about client-server architecture, and don’t integrate well with machine learning constructs like Tensorflow GPU sessions.

I saw this first at Carnegie Mellon, then at Berkeley, Google X, and finally while building autonomous robots at Zoox. These tools were often born as little Jupyter notebooks: the sensor calibration tool, the simulation comparison app, the LIDAR alignment app, the scenario replay tool, and so on.

As a tool grew in importance, project managers stepped in. Processes sprouted. Requirements flowered. These solo projects gestated into scripts, and matured into gangly maintenance nightmares.

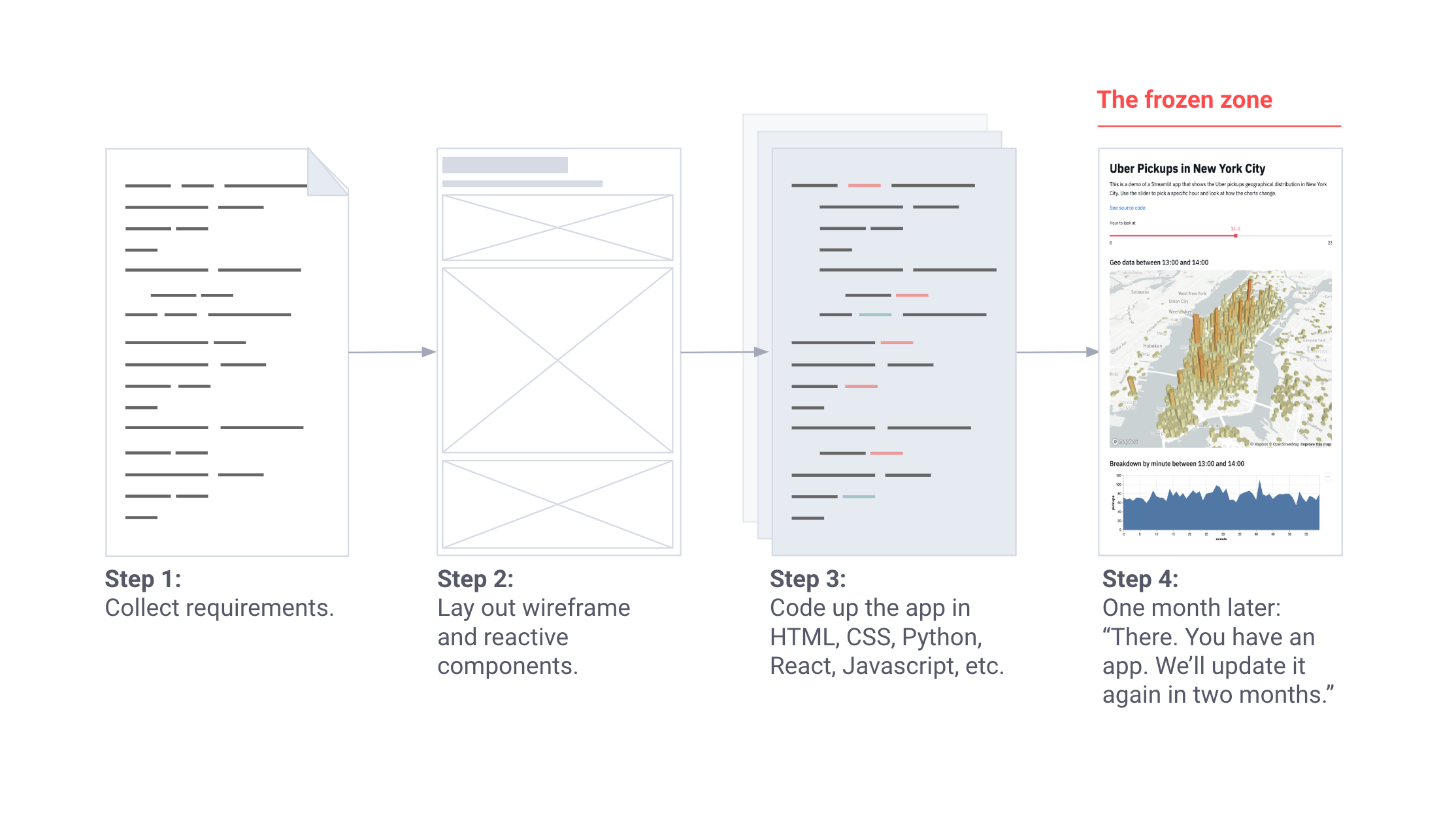

When a tool became crucial, we called in the tools team. They wrote fluent Vue and React. They blinged their laptops with stickers about declarative frameworks. They had a design process:

Which was awesome. But these tools all needed new features, like weekly. And the tools team was supporting ten other projects. They would say, “we’ll update your tool again in two months.”

So we were back to building our own tools, deploying Flask apps, writing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and trying to version control everything from notebooks to stylesheets. So my old Google X friend, Thiago Teixeira, and I began thinking about the following question: What if we could make building tools as easy as writing Python scripts?

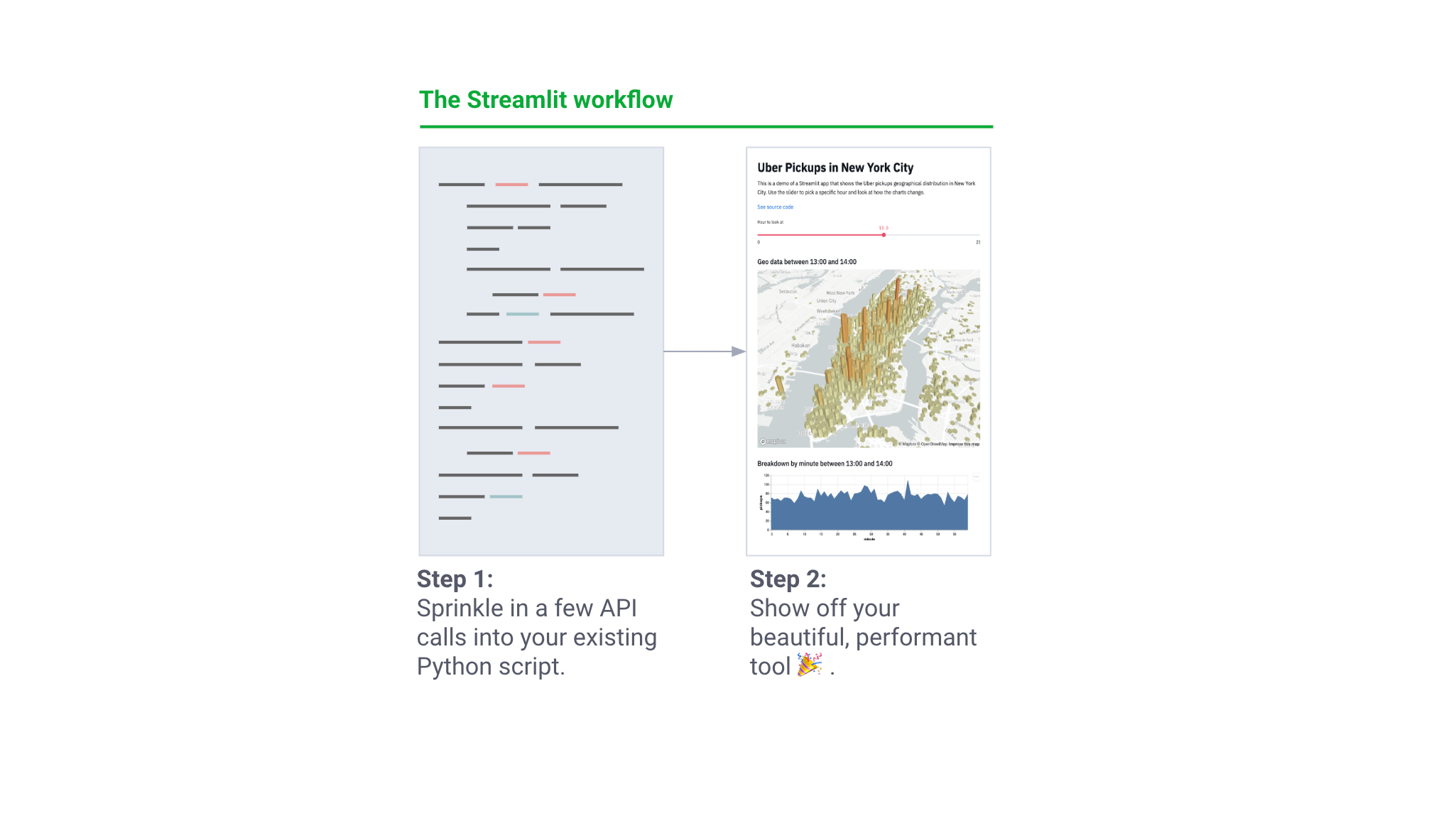

We wanted machine learning engineers to be able to create beautiful apps without needing a tools team. These internal tools should arise as a natural byproduct of the ML workflow. Writing such tools should feel like training a neural net or performing an ad-hoc analysis in Jupyter! At the same time, we wanted to preserve all of the flexibility of a powerful app framework. We wanted to create beautiful, performant tools that engineers could show off. Basically, we wanted this:

With an amazing beta community including engineers from Uber, Twitter, Stitch Fix, and Dropbox, we worked for a year to create Streamlit, a completely free and open source app framework for ML engineers. With each prototype, the core principles of Streamlit became simpler and purer. They are:

1: Embrace Python scripting.

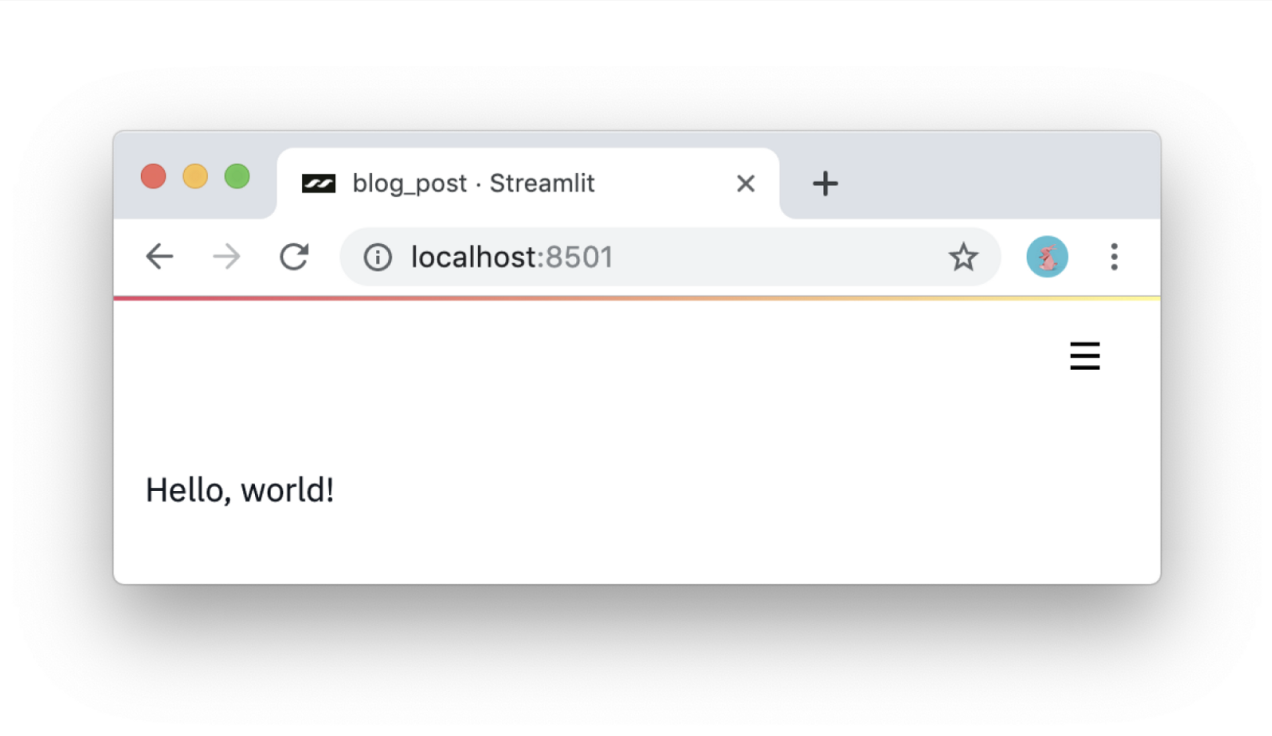

Streamlit apps are really just scripts that run from top to bottom. There’s no hidden state. You can factor your code with function calls. If you know how to write Python scripts, you can write Streamlit apps. For example, this is how you write to the screen:

import streamlit as st

st.write('Hello, world!')

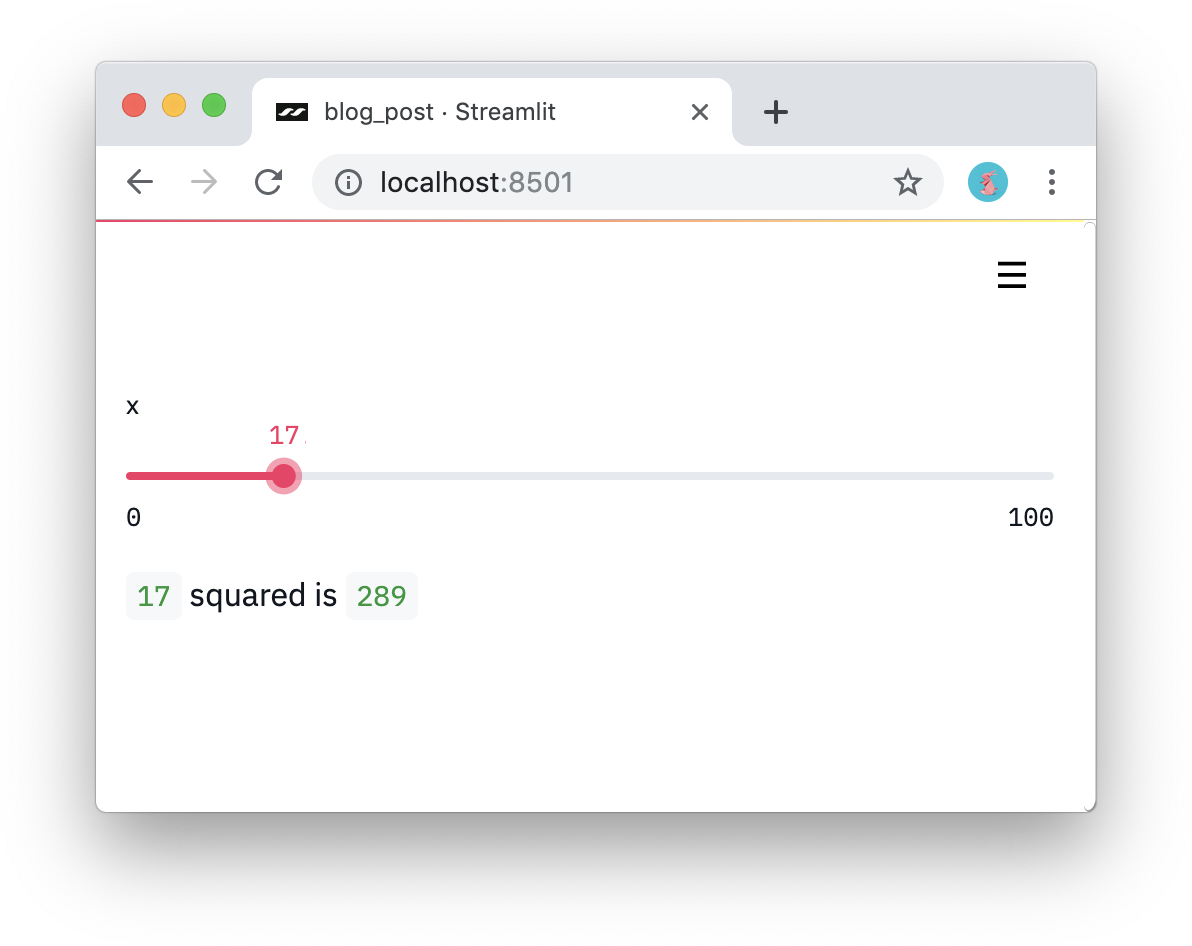

2: Treat widgets as variables.

There are no callbacks in Streamlit! Every interaction simply reruns the script from top to bottom. This approach leads to really clean code:

import streamlit as st

x = st.slider('x')

st.write(x, 'squared is', x * x)

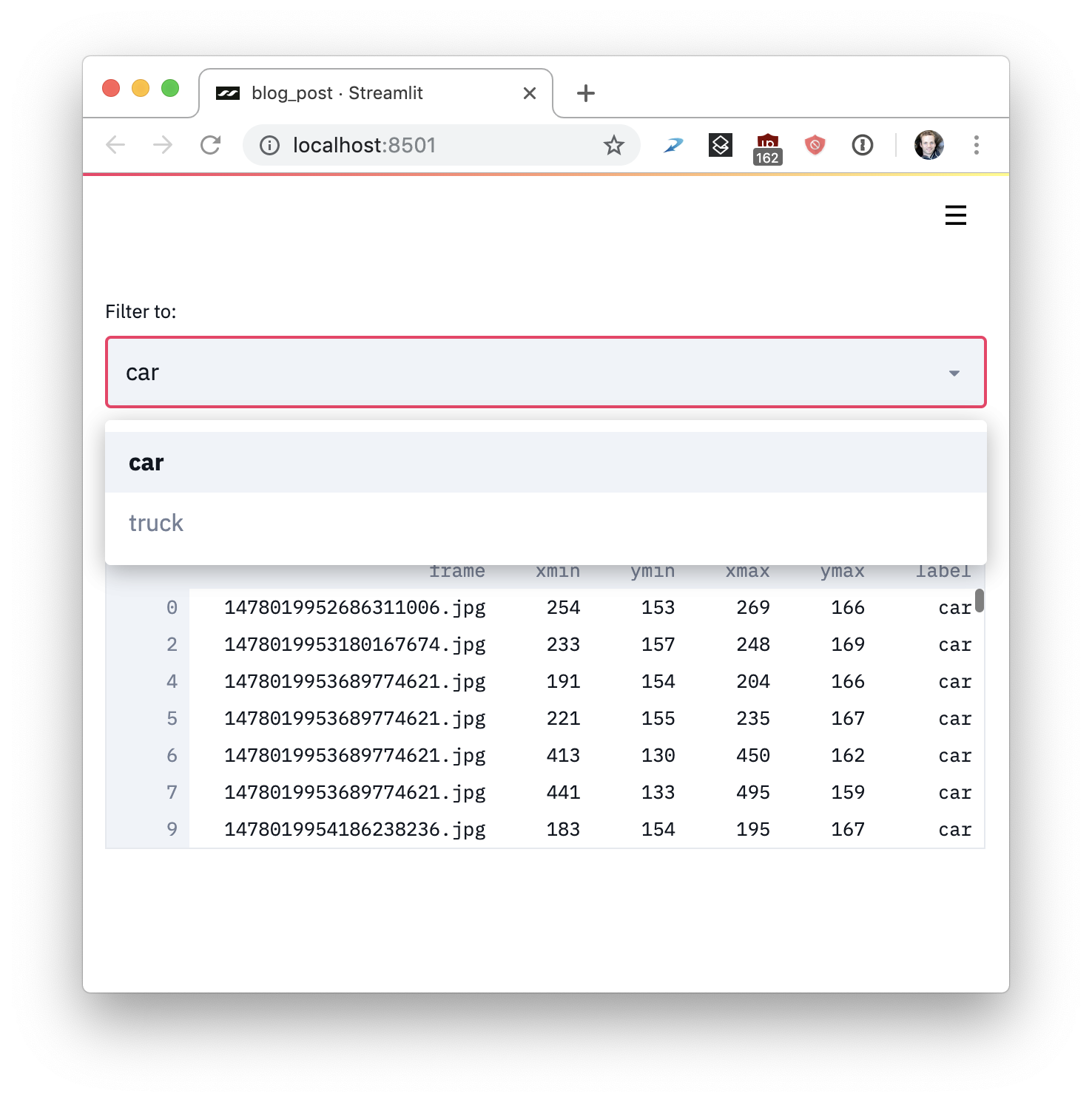

3: Reuse data and computation.

What if you download lots of data or perform complex computation? The key is to safely reuse information across runs. Streamlit introduces a cache primitive that behaves like a persistent, immutable-by-default, data store that lets Streamlit apps safely and effortlessly reuse information. For example, this code downloads data only once from the Udacity Self-driving car project, yielding a simple, fast app:

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

# Reuse this data across runs!

read_and_cache_csv = st.cache(pd.read_csv)

BUCKET = "https://streamlit-self-driving.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/"

data = read_and_cache_csv(BUCKET + "labels.csv.gz", nrows=1000)

desired_label = st.selectbox('Filter to:', ['car', 'truck'])

st.write(data[data.label == desired_label])

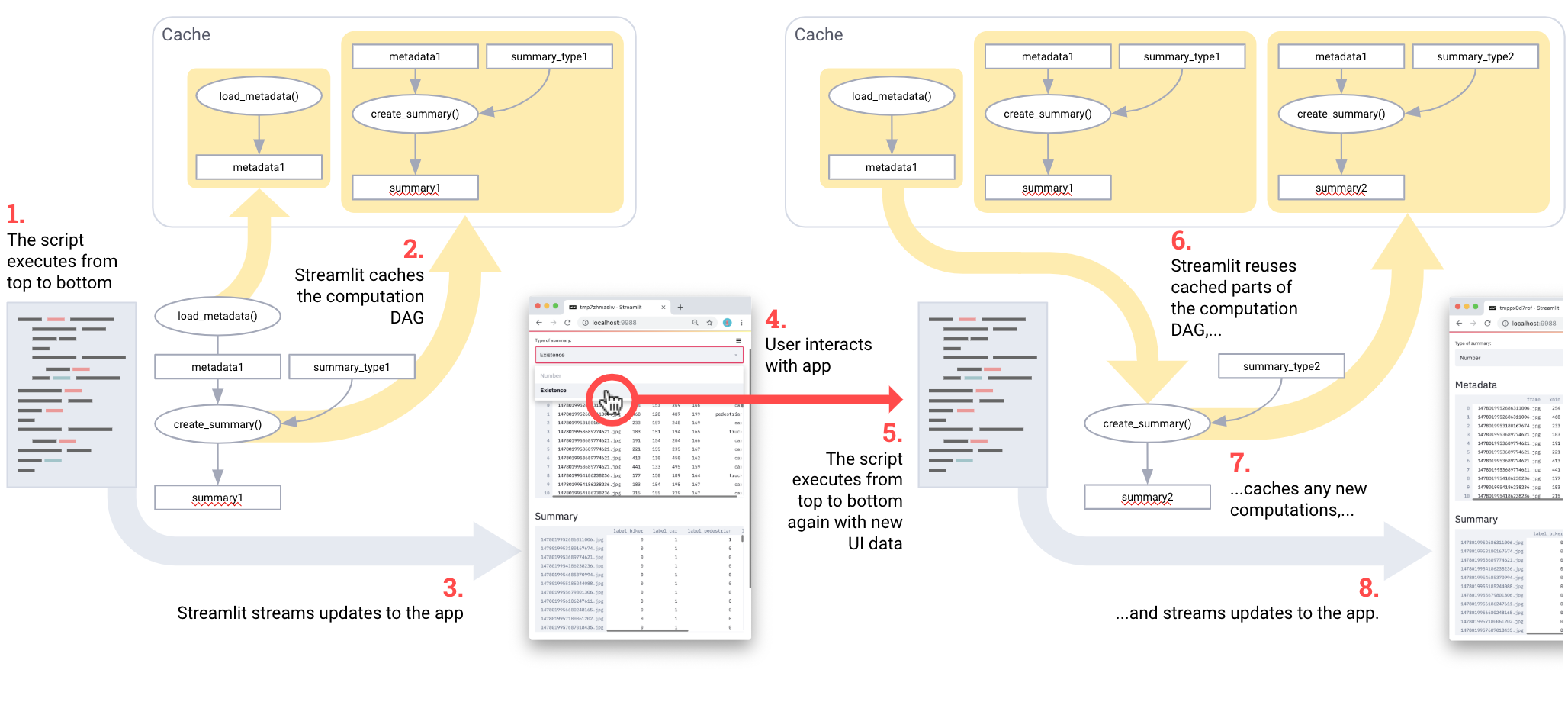

In short, Streamlit works like this:

- The entire script is run from scratch for each user interaction.

- Streamlit assigns each variable an up-to-date value given widget states.

- Caching allows Streamlit to skip redundant data fetches and computation.

Or in pictures:

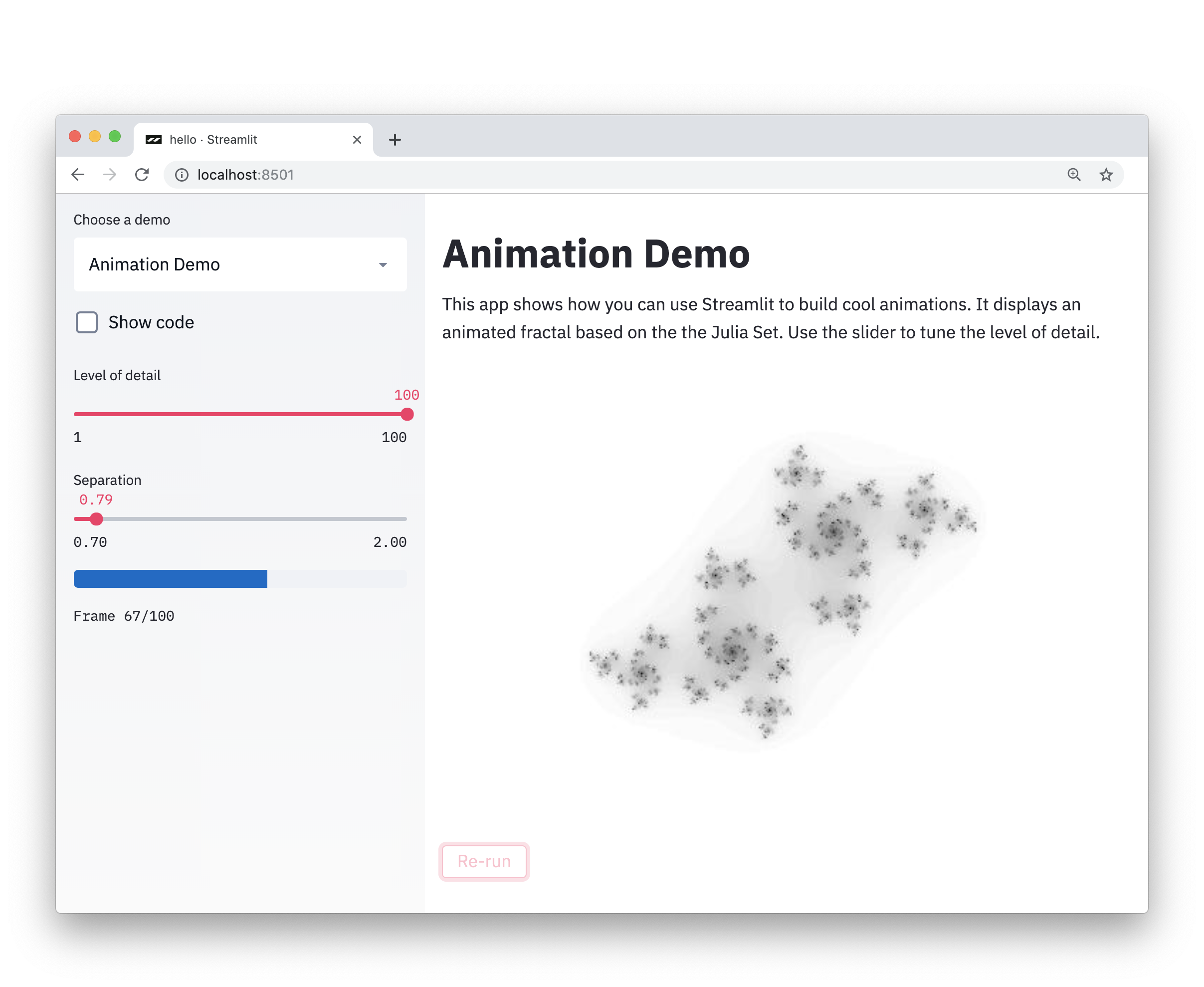

If this sounds intriguing, you can try it right now! Just run:

$ pip install --upgrade streamlit

$ streamlit hello

You can now view your Streamlit app in your browser.

Local URL: http://localhost:8501

Network URL: http://10.0.1.29:8501

This will automatically pop open a web browser pointing to your local Streamlit app. If not, just click the link.

Ok. Are you back from playing with fractals? Those can be mesmerizing.

The simplicity of these ideas does not prevent you from creating incredibly rich and useful apps with Streamlit. During my time at Zoox and Google X, I watched as self-driving car projects ballooned into gigabytes of visual data, which needed to be searched and understood, including running models on images to compare performance. Every self-driving car project I’ve seen eventually has had entire teams working on this tooling.

Building such a tool in Streamlit is easy. This Streamlit demo lets you perform semantic search across the entire Udacity self-driving car photo dataset, visualize human-annotated ground truth labels, and run a complete neural net (YOLO) in real time from within the app [1].

The whole app is a completely self-contained, 300-line Python script, most of which is machine learning code. In fact, there are only 23 Streamlit calls in the whole app. You can run it yourself right now!

$ pip install --upgrade streamlit opencv-python

$ streamlit run

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/streamlit/demo-self-driving/master/app.py

As we worked with machine learning teams on their own projects, we came to realize that these simple ideas yield a number of important benefits:

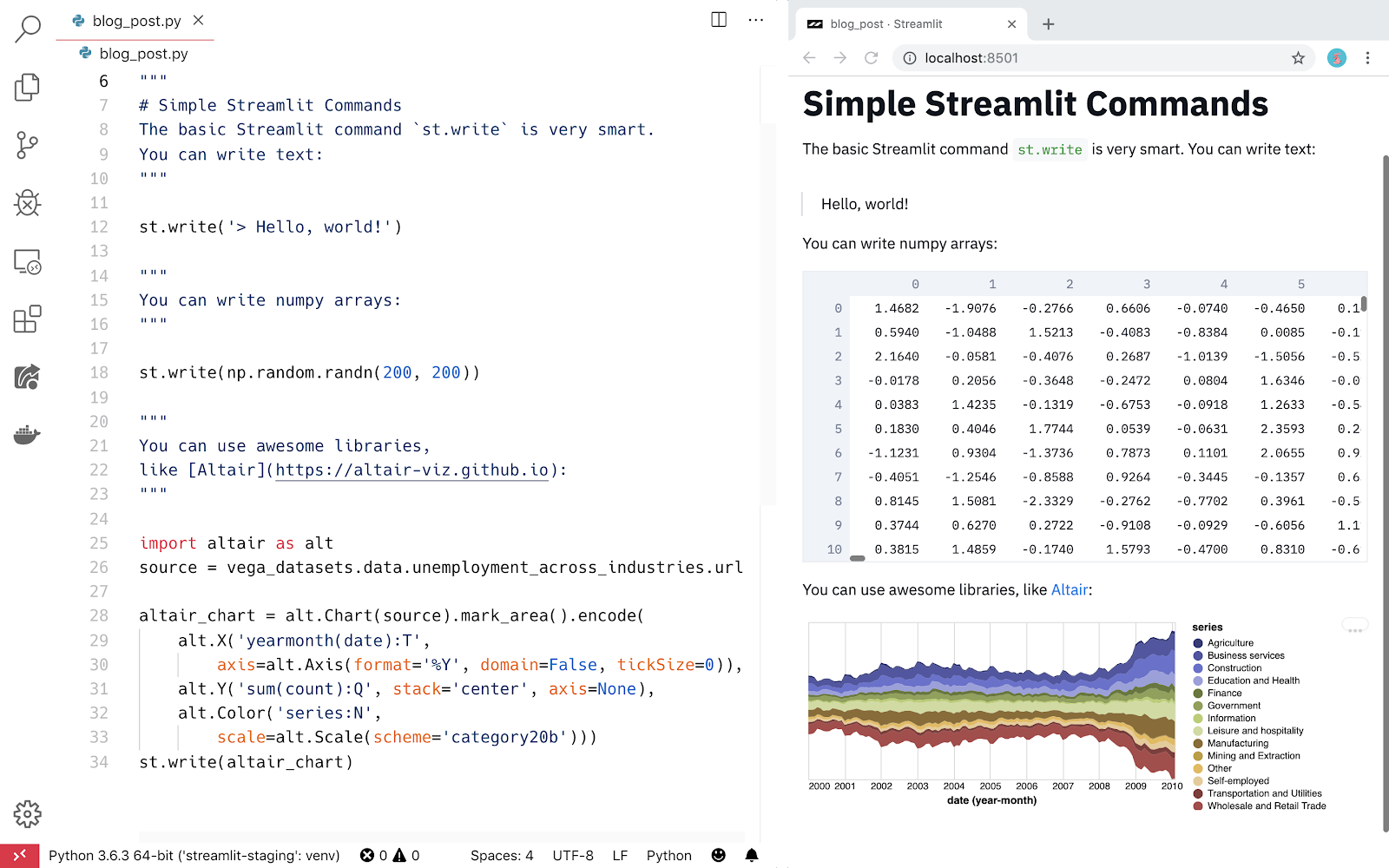

Streamlit apps are pure Python files.

So you can use your favorite editor and debugger with Streamlit.

Pure Python scripts work seamlessly with Git and other source control software, including commits, pull requests, issues, and comments. Because Streamlit’s underlying language is pure Python, you get all the benefits of these amazing collaboration tools for free 🎉.

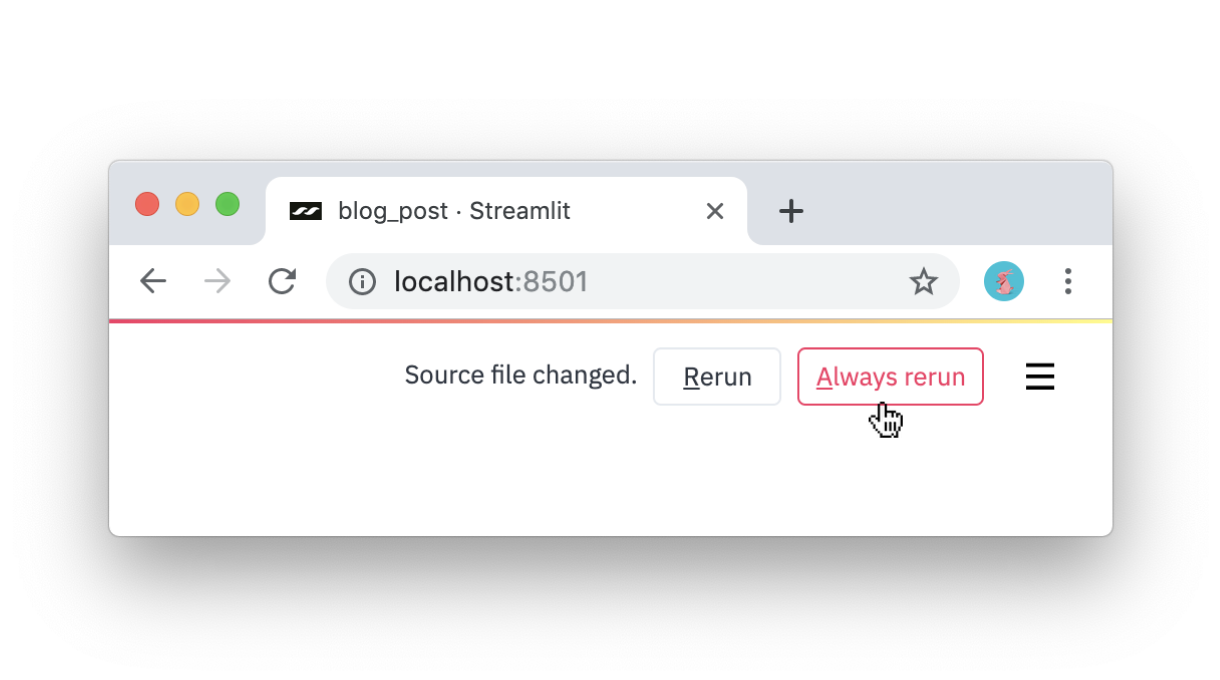

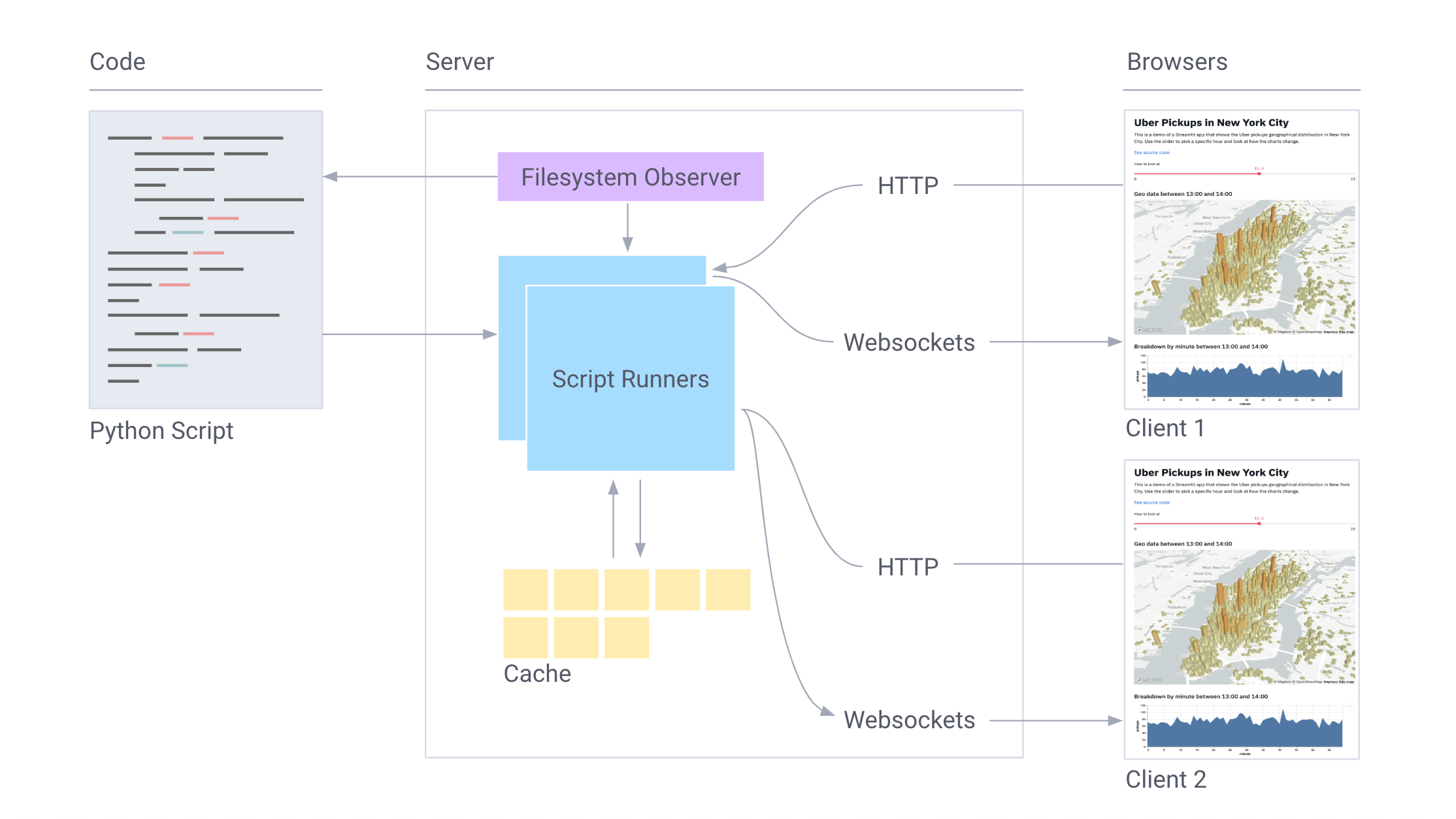

Streamlit provides an immediate-mode live coding environment. Just click Always rerun when Streamlit detects a source file change.

Caching simplifies setting up computation pipelines. Amazingly, chaining cached functions automatically creates efficient computation pipelines! Consider this code adapted from our Udacity demo:

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

@st.cache

def load_metadata():

DATA_URL = "https://streamlit-self-driving.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/labels.csv.gz"

return pd.read_csv(DATA_URL, nrows=1000)

@st.cache

def create_summary(metadata, summary_type):

one_hot_encoded = pd.get_dummies(metadata[["frame", "label"]], columns=["label"])

return getattr(one_hot_encoded.groupby(["frame"]), summary_type)()

# Piping one st.cache function into another forms a computation DAG.

summary_type = st.selectbox("Type of summary:", ["sum", "any"])

metadata = load_metadata()

summary = create_summary(metadata, summary_type)

st.write('## Metadata', metadata, '## Summary', summary)

Basically, the pipeline is load_metadata → create_summary. Every time the script is run Streamlit only recomputes whatever subset of the pipeline is required to get the right answer. Cool!

Streamlit is built for GPUs. Streamlit allows direct access to machine-level primitives like TensorFlow and PyTorch and complements these libraries. For example in this demo, Streamlit’s cache stores the entire NVIDIA celebrity face GAN [2]. This approach enables nearly instantaneous inference as the user updates sliders.

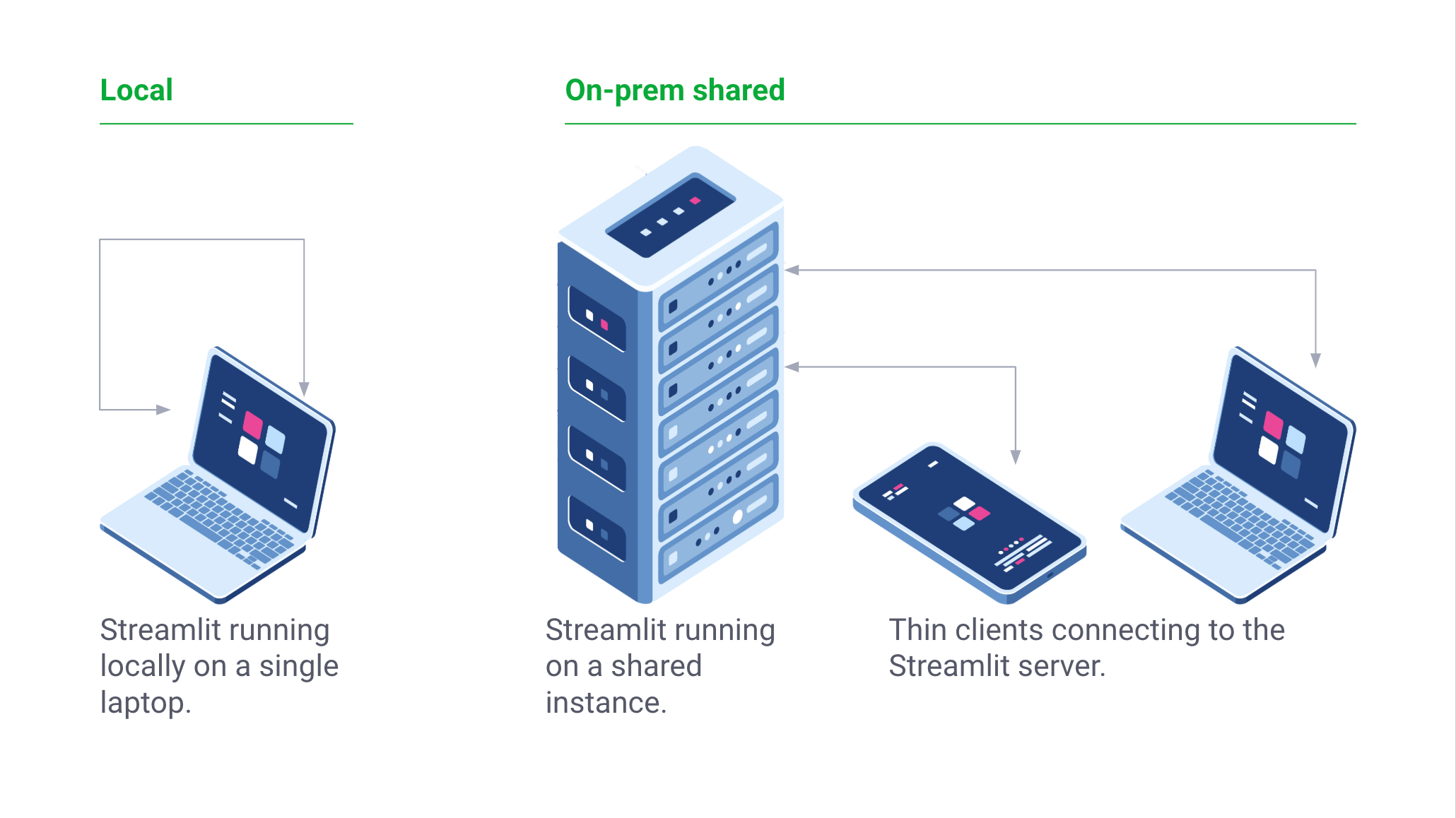

Streamlit is a free and open-source library rather than a proprietary web app. You can serve Streamlit apps on-prem without contacting us. You can even run Streamlit locally on a laptop without an Internet connection! Furthermore, existing projects can adopt Streamlit incrementally.

This just scratches the surface of what you can do with Streamlit. One of the most exciting aspects of Streamlit is how these primitives can be easily composed into complex apps that look like scripts. There’s a lot more we could say about how our architecture works and the features we have planned, but we’ll save that for future posts.

We’re excited to finally share Streamlit with the community today and see what you all build with it. We hope that you’ll find it easy and delightful to turn your Python scripts into beautiful ML apps.

#python #machine-learning