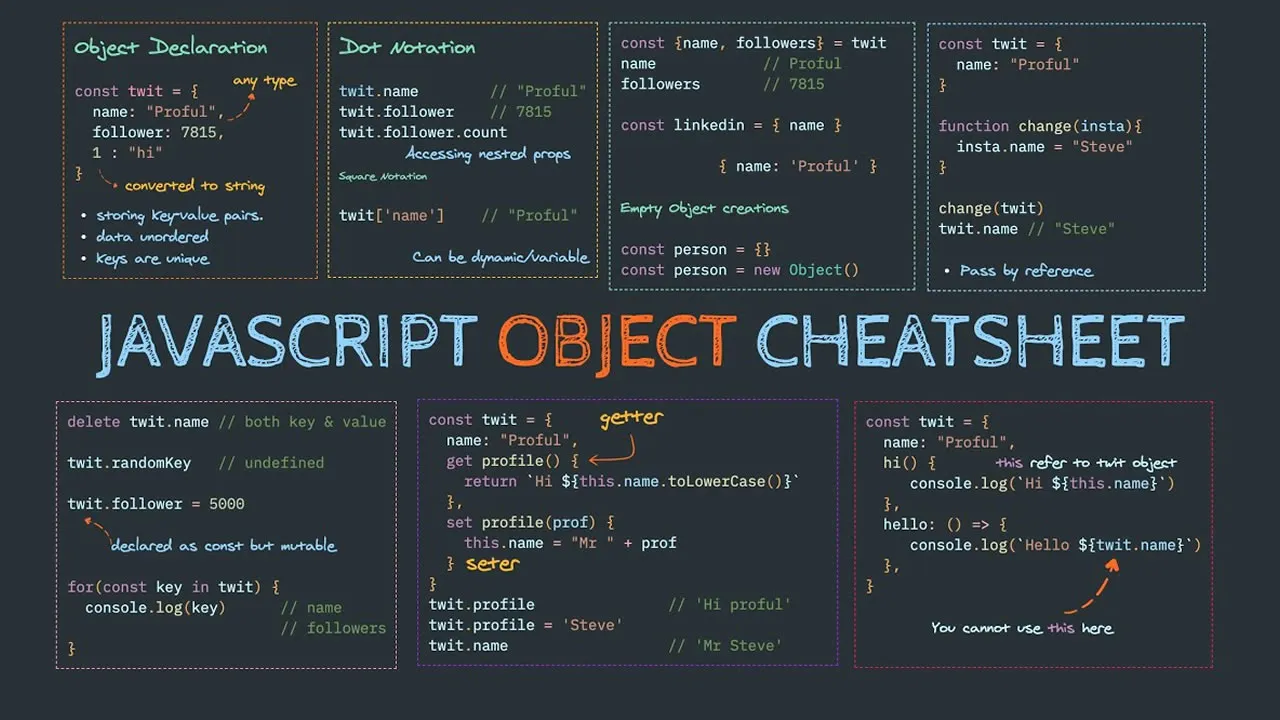

JavaScript Object Cheatsheet: Everything You Need to Know

Master JavaScript objects with this comprehensive cheatsheet! This comprehensive JavaScript object cheatsheet is the perfect resource for anyone who wants to learn everything there is to know about objects in JavaScript. Covering a wide range of topics, from basic object creation to advanced object methods, this cheatsheet has everything you need to start using objects effectively in your code.

Restrictions in Naming Properties

JavaScript object key names must adhere to some restrictions to be valid. Key names must either be strings or valid identifier or variable names (i.e. special characters such as - are not allowed in key names that are not strings).

// Example of invalid key names

const trainSchedule = {

platform num: 10, // Invalid because of the space between words.

40 - 10 + 2: 30, // Expressions cannot be keys.

+compartment: 'C' // The use of a + sign is invalid unless it is enclosed in quotations.

}Dot Notation for Accessing Object Properties

Properties of a JavaScript object can be accessed using the dot notation in this manner: object.propertyName. Nested properties of an object can be accessed by chaining key names in the correct order.

const apple = {

color: 'Green',

price: {

bulk: '$3/kg',

smallQty: '$4/kg'

}

};

console.log(apple.color); // 'Green'

console.log(apple.price.bulk); // '$3/kg'Objects

An object is a built-in data type for storing key-value pairs. Data inside objects are unordered, and the values can be of any type.

Accessing non-existent JavaScript properties

When trying to access a JavaScript object property that has not been defined yet, the value of undefined will be returned by default.

const classElection = {

date: 'January 12'

};

console.log(classElection.place); // undefinedJavaScript Objects are Mutable

JavaScript objects are mutable, meaning their contents can be changed, even when they are declared as const. New properties can be added, and existing property values can be changed or deleted.

It is the reference to the object, bound to the variable, that cannot be changed.

const student = {

name: 'Sheldon',

score: 100,

grade: 'A',

}

console.log(student)

// { name: 'Sheldon', score: 100, grade: 'A' }

delete student.score

student.grade = 'F'

console.log(student)

// { name: 'Sheldon', grade: 'F' }

student = {}

// TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.JavaScript for...in loop

The JavaScript for...in loop can be used to iterate over the keys of an object. In each iteration, one of the properties from the object is assigned to the variable of that loop.

let mobile = {

brand: 'Samsung',

model: 'Galaxy Note 9'

};

for (let key in mobile) {

console.log(`${key}: ${mobile[key]}`);

}Properties and values of a JavaScript object

A JavaScript object literal is enclosed with curly braces {}. Values are mapped to keys in the object with a colon (:), and the key-value pairs are separated by commas. All the keys are unique, but values are not.

Key-value pairs of an object are also referred to as properties.

const classOf2018 = {

students: 38,

year: 2018

}Delete operator

Once an object is created in JavaScript, it is possible to remove properties from the object using the delete operator. The delete keyword deletes both the value of the property and the property itself from the object. The delete operator only works on properties, not on variables or functions.

const person = {

firstName: "Matilda",

age: 27,

hobby: "knitting",

goal: "learning JavaScript"

};

delete person.hobby; // or delete person[hobby];

console.log(person);

/*

{

firstName: "Matilda"

age: 27

goal: "learning JavaScript"

}

*/

javascript passing objects as arguments

When JavaScript objects are passed as arguments to functions or methods, they are passed by reference, not by value. This means that the object itself (not a copy) is accessible and mutable (can be changed) inside that function.

const origNum = 8;

const origObj = {color: 'blue'};

const changeItUp = (num, obj) => {

num = 7;

obj.color = 'red';

};

changeItUp(origNum, origObj);

// Will output 8 since integers are passed by value.

console.log(origNum);

// Will output 'red' since objects are passed

// by reference and are therefore mutable.

console.log(origObj.color);JavaScript Object Methods

JavaScript objects may have property values that are functions. These are referred to as object methods.

Methods may be defined using anonymous arrow function expressions, or with shorthand method syntax.

Object methods are invoked with the syntax: objectName.methodName(arguments).

const engine = {

// method shorthand, with one argument

start(adverb) {

console.log(`The engine starts up ${adverb}...`);

},

// anonymous arrow function expression with no arguments

sputter: () => {

console.log('The engine sputters...');

},

};

engine.start('noisily');

engine.sputter();

/* Console output:

The engine starts up noisily...

The engine sputters...

*/JavaScript destructuring assignment shorthand syntax

The JavaScript destructuring assignment is a shorthand syntax that allows object properties to be extracted into specific variable values.

It uses a pair of curly braces ({}) with property names on the left-hand side of an assignment to extract values from objects. The number of variables can be less than the total properties of an object.

const rubiksCubeFacts = {

possiblePermutations: '43,252,003,274,489,856,000',

invented: '1974',

largestCube: '17x17x17'

};

const {possiblePermutations, invented, largestCube} = rubiksCubeFacts;

console.log(possiblePermutations); // '43,252,003,274,489,856,000'

console.log(invented); // '1974'

console.log(largestCube); // '17x17x17'shorthand property name syntax for object creation

The shorthand property name syntax in JavaScript allows creating objects without explicitly specifying the property names (ie. explicitly declaring the value after the key). In this process, an object is created where the property names of that object match variables which already exist in that context. Shorthand property names populate an object with a key matching the identifier and a value matching the identifier’s value.

const activity = 'Surfing';

const beach = { activity };

console.log(beach); // { activity: 'Surfing' }this Keyword

The reserved keyword this refers to a method’s calling object, and it can be used to access properties belonging to that object.

Here, using the this keyword inside the object function to refer to the cat object and access its name property.

const cat = {

name: 'Pipey',

age: 8,

whatName() {

return this.name

}

};

console.log(cat.whatName());

// Output: Pipeyjavascript function this

Every JavaScript function or method has a this context. For a function defined inside of an object, this will refer to that object itself. For a function defined outside of an object, this will refer to the global object (window in a browser, global in Node.js).

const restaurant = {

numCustomers: 45,

seatCapacity: 100,

availableSeats() {

// this refers to the restaurant object

// and it's used to access its properties

return this.seatCapacity - this.numCustomers;

}

}

JavaScript Arrow Function this Scope

JavaScript arrow functions do not have their own this context, but use the this of the surrounding lexical context. Thus, they are generally a poor choice for writing object methods.

Consider the example code:

loggerA is a property that uses arrow notation to define the function. Since data does not exist in the global context, accessing this.data returns undefined.

loggerB uses method syntax. Since this refers to the enclosing object, the value of the data property is accessed as expected, returning "abc".

const myObj = {

data: 'abc',

loggerA: () => { console.log(this.data); },

loggerB() { console.log(this.data); },

};

myObj.loggerA(); // undefined

myObj.loggerB(); // 'abc'getters and setters intercept property access

JavaScript getter and setter methods are helpful in part because they offer a way to intercept property access and assignment, and allow for additional actions to be performed before these changes go into effect.

const myCat = {

_name: 'Snickers',

get name(){

return this._name

},

set name(newName){

//Verify that newName is a non-empty string before setting as name property

if (typeof newName === 'string' && newName.length > 0){

this._name = newName;

} else {

console.log("ERROR: name must be a non-empty string");

}

}

}javascript factory functions

A JavaScript function that returns an object is known as a factory function. Factory functions often accept parameters in order to customize the returned object.

// A factory function that accepts 'name',

// 'age', and 'breed' parameters to return

// a customized dog object.

const dogFactory = (name, age, breed) => {

return {

name: name,

age: age,

breed: breed,

bark() {

console.log('Woof!');

}

};

};

javascript getters and setters restricted

JavaScript object properties are not private or protected. Since JavaScript objects are passed by reference, there is no way to fully prevent incorrect interactions with object properties.

One way to implement more restricted interactions with object properties is to use getter and setter methods.

Typically, the internal value is stored as a property with an identifier that matches the getter and setter method names, but begins with an underscore (_).

const myCat = {

_name: 'Dottie',

get name() {

return this._name;

},

set name(newName) {

this._name = newName;

}

};

// Reference invokes the getter

console.log(myCat.name);

// Assignment invokes the setter

myCat.name = 'Yankee';

Object.assign()

copies properties from one or more source objects to target object

// example

Object.assign({ a: 1, b: 2 }, { c: 3 }, { d: 4 }) // { a: 1, b: 2, c: 3, d: 4 }

// syntax

Object.assign(target, ...sources)

Object.create()

creates new object, using an existing object as the prototype

// example

Object.create({ a: 1 }) // <prototype>: Object { a: 1 }

// syntax

Object.create(proto, [propertiesObject])

Object.defineProperties()

defines new or modifies existing properties

// example

Object.defineProperties({ a: 1, b: 2 }, { a: {

value: 3,

writable: true,

}}) // { a: 3, b: 2 }

// syntax

Object.defineProperties(obj, props)

Object.defineProperty()

defines new or modifies existing property

// example

Object.defineProperty({ a: 1, b: 2 }, 'a', {

value: 3,

writable: true

}); // { a: 3, b: 2 }

// syntax

Object.defineProperty(obj, prop, descriptor)

Object.entries()

returns array of object's [key, value] pairs

// example

Object.entries({ a: 1, b: 2 }) // [ ["a", 1], ["b", 2] ]

// syntax

Object.entries(obj)

Object.freeze()

freezes an object, which then can no longer be changed

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

Object.freeze(obj)

obj.prop = 2 // error in strict mode

console.log(obj.prop) // 1

// syntax

Object.freeze(obj)

Object.fromEntries()

transforms a list of key-value pairs into an object

// example

Object.fromEntries([['a', 1], ['b', 2]]) // { a: 1, b: 2 }

// syntax

Object.fromEntries(iterable)

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor()

returns a property descriptor for an own property

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, 'a') // { value: 1, writable: true, enumerable: true, configurable: true }

// syntax

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, prop)

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors()

returns all own property descriptors

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors(obj, 'a') // { a: { value: 1, writable: true, enumerable: true, configurable: true } }

// syntax

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, prop)

Object.getOwnPropertyNames()

returns array of all properties

// example

Object.getOwnPropertyNames({ a: 1, b: 2 }) // [ "a", "b" ]

// syntax

Object.getOwnPropertyNames(obj)

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols()

array of all symbol properties

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

const b = Symbol('b')

obj[b] = 'someSymbol' // obj = { a: 1, Symbol(b): "symbol" }

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(obj) // [ Symbol(b) ]

// syntax

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(obj)

Object.getPrototypeOf()

returns the prototype

// example

const proto = { a: 1 }

const obj = Object.create(proto)

obj.b = 2 // obj = { b: 2 }

Object.getPrototypeOf(obj) // { a: 1 }

// syntax

Object.getPrototypeOf(obj)

Object.is()

determines whether two values are the same value

// example

const objA = { a: 1 }

const objB = { a: 1 }

Object.is(objA, objA) // true

Object.is(objA, objB) // false

Object.is('a', 'a') // true

// syntax

Object.is(value1, value2)

Object.isExtensible()

determines wether an object can have new properties added to it

// example

const obj = {}

Object.isExtensible(obj) // true

Object.preventExtensions(obj)

Object.isExtensible(obj) // false

// syntax

Object.isExtensible(obj)

Object.isFrozen()

determines if an object is frozen

// example

const obj = {}

Object.isFrozen(obj) // false

Object.freeze(obj)

Object.isFrozen(obj) // true

// syntax

Object.isFrozen(obj)

Object.isSealed()

determines if an object is sealed

// example

const obj = {}

Object.isSealed(obj) // false

Object.seal(obj)

Object.isSealed(obj) // true

// syntax

Object.isSealed(obj)

Object.keys()

returns array of object's enumerable property names

// example

Object.keys({ a: 1, b: 2 }) // [ "a", "b" ]

// syntax

Object.keys(obj)

Object.preventExtensions()

prevents new properties from being added to an object

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

Object.preventExtensions(obj)

Object.defineProperty(obj, 'b', { value: 2 }) // Error: Can't define property "b": Object is not extensible

// syntax

Object.preventExtensions(obj)

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty()

returns boolean indicating whether object has the specified property

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

obj.hasOwnProperty('a') // true

obj.hasOwnProperty('b') // false

// syntax

obj.hasOwnProperty(prop)

Object.prototype.isPrototypeOf()

checks if object exists in another object's prototype chain

// example

const proto = { a: 1 }

const obj = Object.create(proto)

proto.isPrototypeOf(obj) // true

// syntax

prototypeObj.isPrototypeOf(object)

Object.prototype.propertyIsEnumerable()

checks whether the specified property is enumerable and is the object's own property

// example

const obj = { a: 1 } const arr = ['a']

obj.propertyIsEnumerable('a') // true

arr.propertyIsEnumerable(0) // true

arr.propertyIsEnumerable('length') // false

// syntax

obj.propertyIsEnumerable(prop)

Object.prototype.toString()

returns a string representing the object

// example

const obj = {}

obj.toString() // "[object Object]"

const arr = ['a', 'b']

arr.toString() // "a,b"

// syntax

obj.toString()

Object.seal()

prevents new properties from being added and marks all existing properties as non-configurable

// example

const obj = { a: 1 }

Object.seal(obj)

obj.a = 2 // { a: 2 }

obj.b = 3 // error in strict mode

delete obj.a // error in strict mode

// syntax

Object.seal(obj)

Object.values()

returns array of object's own enumerable property values

// example

Object.values({ a: 1, b: 'a'}) // [ 1, "a" ]

// syntax

Object.values(obj)

Creating

const objectName = {};

Adding

1. Using . dot notation:

objectName.name = "Rabah";

objectName.age = 18;

2. Using [] bracket notation:

objectName["name"] = "Rabah";

objectName["age"] = 18;

// another way with variables

const newProp = 'location';

objectName[newProp] = 'FL'

/*

objectName = {

name: "Rabah",

age: 18,

location: "FL"

}

*/

Accessing

// dot notation

objectName.name; // "Rabah"

// bracket notation

objectName["name"]; // "Rabah"

// extra variation

const propName = "location";

objectName[propName] // "FL"

Manipulating

objectName.age = 25;

objectName["age"] = 25 // 25

Looping

for (let property in objectName) {

if (property === ...) {

// Do things here

} else {

// do something otherwise

}

}

Cloning keys

const objectKeys = [];

for (let property in objectName) {

objectKeys.push(property);

}

console.log(objectKeys) // ["name", "age", "location"]

// alternatively

const keys = Object.keys(objectName);

console.log(keys) // ["name", "age", "location"]

Cloning values

const objectValues = [];

for (let property in objectName) {

objectValues.push(objectName[property]);

}

console.log(objectValues) // ["Rabah", 25, "FL"]

// alternatively

const values = Object.values(objectName);

console.log(values) // ["Rabah", 25, "FL"]

in operator

if ("favoriteColor" in objectName) { // if the property favoriteColor exists in objectName

// do something if true

} else {

// do something otherwise

}

Defining methods

// The same way we add properties

objectName.sayBonjour = function(name) {

console.log(`Bonjour ${name}.`);

}

Using methods

objectName.sayBonjour("Peggy"); // "Bonjour Peggy."

this keyword

// Let's add a new method

objectName.sayMyAge = function() {

this.sayBonjour('Mathieu');

console.log(`You're ${this.age} years old.`);

}

Explanation:

// Now our object looks like this

objectName = {

name: "Rabah",

age: 25,

location: "FL",

sayBonjour: function(name) {

console.log(`Bonjour ${name}.`);

},

sayMyAge: function() {

this.sayBonjour('Mathieu');

// Since the method 'sayBonjour' it's outside of this method scope,

// which is inside the objectName. so to refer to it and use it by calling it, we have to use the 'this' keyword.

// Using the 'this.sayBonjour()' keyword is the same thing as saying:

// objectName.sayBonjour()

console.log(`You're ${this.age} years old.`);

// The same thing happening here. We're saying '`I'm ${objectName.age} years old.'

}

}

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

objectName.sayMyAge(); // "Bonjour Mathieu."

// "I'm 25 years old."#javascript #js