Getting started with Flutter

Getting started with Flutter - Part 1: Introduction to Flutter

In this series, we’ll take a look at a new mobile app development framework called Flutter.

In the past few years, many tools were developed to help developers create cross-platform apps. This was brought about by the need to release mobile apps that can run on both Android and iOS platforms a lot more quicker. Having two or more teams working on each platform is expensive, and most startups can’t really afford it. That’s why tools like Cordova, Ionic, React Native, Xamarin, NativeScript, Fuse, and many others were developed.

In this part, you’ll learn what it is, how it works, some of its pros and cons, and how it compares to React Native.

In the second part, you’ll learn how to create an app with Flutter.

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes no previous knowledge of Flutter.

What is Flutter?

Flutter is a new mobile app development SDK from Google. It allows you to develop apps which run on both iOS and Android. Flutter has built-in Material Design and Cupertino widgets which you can use to create beautiful and professional looking apps.

Flutter uses the Dart language for both its SDK and the code written by the developer.

Flutter is a complete framework. This means that everything that you need to build and test a mobile application is included out of the box:

- UI rendering

- Widget library

- Navigation

- State management

- Hardware APIs

- Testing

How does Flutter work?

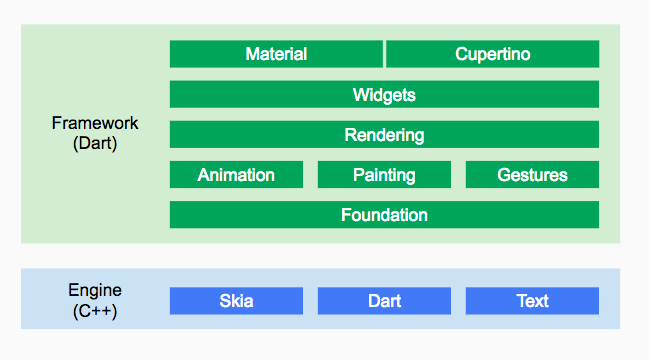

Flutter is built with C, C++, Dart, and Skia, a 2D rendering engine.

Each Flutter app is composed of the Flutter SDK and the Dart code written by the developer. Flutter uses ahead of time (AoT) compiling to compile both the Flutter SDK and the Dart code into a native ARM library. This is then executed by a “runner” that handles all the rendering, input and event handling inside the app.

The diagram below is a high-level representation of the Flutter system architecture. At the very top are the themes for both the Android (Material Design) and iOS (Cupertino) platforms. As the developer, you wrap Flutter’s basic widgets with these themes depending on which platform you’re working with.

Note that these widgets are Flutter’s own widgets, they don’t actually use the platform’s OEM widgets like React Native or NativeScript does. This brings us to the “Rendering” part in the diagram below. Flutter uses Skia to draw these widgets into the screen. If you’re familiar with Unity, Flutter works in a similar way. The underlying framework takes care of the animation, painting, and gestures as the user interacts with the widgets that were rendered. Behind the scenes, Skia takes care of updating what the user sees on the screen. The Flutter SDK and the Dart code written by the developer is executed via the Dart VM.

That was only a quick overview of how Flutter works. If you’re interested in diving deeper, be sure to check out these technical documents:

Pros and cons of Flutter

In this section, we’ll take a quick look at some of Flutter’s advantages and disadvantages. These are in terms of developer productivity, widget support, and app performance. Note that these are true at the time of writing this tutorial. Flutter is in constant development, so what’s missing today might already be supported tomorrow.

Pros

- Flutter is open-source. On top of the dedicated Google team that works on Flutter, everyone is also welcome to contribute to the development of Flutter and publish their own packages.

- Flutter has great documentation. Everything you need to know about the Flutter APIs and internals is well-documented.

- Allows your existing Java, Swift, and Objective-C code to be reused to work with native functionality on iOS and Android.

- Flutter uses its own widgets, not the one which comes with Android and iOS (OEM widgets). This means we don’t have to deal with implementation details for both platforms.

- Performance is very close to native performance. Unlike React Native which needs to go through a “bridge” to interact with native components, Flutter has a “runner” which renders the widgets and handles interactions.

- Flutter comes with nice developer tooling out of the box.

- Flutter’s interop and plugin system are designed to allow developers to access new mobile OS features and capabilities immediately when Apple or Google releases them.

Cons

- Fewer widgets are available for iOS. Flutter’s Cupertino widget library lacks some of the essentials like the datepicker, stepper, and progress indicator.

- Doesn’t have much support when it comes to text-editors and IDE’s. Currently, it’s only compatible with IntelliJ IDEA, Visual Studio Code, and Android Studio.

- Unlike in React Native, styling is a bit messier in Flutter. Each widget has their own styling which you put right in the rendering code. Each widget can have children so things can get really messy because the structure and styling are mixed together.

- You can’t transfer your existing CSS knowledge to style your widgets. Though a few concepts still apply (for example, margins and paddings), CSS properties and values are not applicable to Flutter.

- Not a lot of third-party library support. If you need to use services like Auth0, Pusher, Twilio, or Realm, you will most likely have to create your own custom integration.

- No built-in support for common functionality such as maps and camera. Though you might find someone who’s currently working on it on the Dart packages website.

- Flutter hasn’t been tested on tablets so there might be some UI issues on tablets. At the time of writing this article, tablet support isn’t really a priority so be sure to check out this issue to keep track of tablet support if you plan on developing for tablets.

How does Flutter compare to React Native?

The most popular cross-platform app development framework today is React Native, so developers trying to check out Flutter will naturally come to ask this question: “How does Flutter compare to React Native?”.

If you do a quick Google search, you will come across articles which compare the two, and probably with some other framework like Ionic, NativeScript, and Xamarin. There are probably others, but the main question you’re really asking is: “is Flutter a viable solution for cross-platform app development?”. And that’s why I chose React Native as the framework to compare with Flutter. Because it’s already been battle-tested, lots of well-known companies are using it and it has a huge community behind it.

We will be using the following criteria for comparing the two:

- Developer Productivity

- User Experience

- Hardware API Support

The criteria above are arranged according to its level of importance. Developer Productivity and User Experience are more important while Hardware API Support is less important. Note that this prioritization is hugely based on my own personal experience as well as the research that went into writing this article.

Developer productivity

We already know that both React Native and Flutter allow us to write code once and it will run everywhere. If you have worked with React Native in a fair amount of time, you already know that this isn’t completely true. You still have to deal with configuration files (Podfile, build.gradle) on both platforms, you still have to deal with the different UI implementations, and work with either Java, Objective-C, or Swift code whenever you need to work with native functionality.

In Flutter, things are a bit different. You still have the android and ios folders in your project but most of the time you won’t really need to touch the files in there.

How fast the hot reload is is another important factor. Nothing kills productivity more than having to wait a minute for one simple change to show up in the live preview. Both React Native and Flutter have a hot reload feature, but the one in Flutter is faster.

Other than that, there are other areas which developer productivity depends on:

- Documentation

- Learning curve

- Community

- Tooling

Documentation

The first thing that developers will look at when learning a new technology is the documentation, so it plays a big role in developer productivity. Even advanced users will need to use it from time to time when they’re working with a new API.

If you give yourself a few minutes to scan through the documentation of React Native and Flutter, you will quickly see the effort that went into creating the documentation. The documentation is not just about describing the different APIs, functionalities, components and other features that are available in the framework. It’s also about making it easy for both newcomers and advanced users to find what they need to know about.

React Native’s documentation is very shallow, it teaches you one thing and then moves on to the next. It doesn’t allow you to easily dig deeper into one specific concept. If you’re a React Native developer, you might have noticed that there are lots of poorly documented (or not documented at all) APIs. So you have to look for it somewhere else, or just go on with your life not knowing that such capability (or bug) exists.

Flutter’s documentation is very easy to use, all the important concepts and features that you need to know are visible in their sidebar. If you want to dig deeper, they also have API documentation. For example, all the classes that are available for constructing widgets with the material library are well-documented. It includes information about what the constructor expects, which properties you can pass in. Best of all, their search has auto-suggest, this is very helpful if you’re not exactly sure what you’re looking for.

They even take one step further with their Codelabs section, where it teaches the beginners how to create their very first Flutter app.

Learning curve

The learning curve is the rate at which developers can learn a new technology. Though we can’t disregard the fact that previous experience can make the learning curve less steep. With that in mind, we’ll consider that developers can have previous experience with web technology, JavaScript, CSS, and programming as well.

This is where React Native takes the crown. Developers who have worked with JavaScript, CSS, and especially React, will easily feel at home when working with React Native. Their experience in creating components, stylesheets, and web APIs will make it easier to pick up React Native. All they have to learn about are the differences between the web and mobile environment, hardware APIs, and the third-party modules that they need to use. After that, they should be pretty productive when working with React Native.

On the other hand, Flutter uses Dart, a not so popular technology (according to the Stack Overflow developer survey 2018 at least), as the language for writing Flutter apps. But if you’ve worked with JavaScript before, Dart syntax should be pretty familiar.

They also introduced the idea that everything is a widget, and that includes adding styles to other widgets:

new Padding(

padding: new EdgeInsets.all(8.0),

child: const Card(child: const Text('Hello World!')),

)

In the code above, we’re adding an 8px padding all around a card widget. Just by looking at this code, you’ll see that you can’t really transfer your existing CSS knowledge in styling Flutter apps, although basic concepts like margin and padding still apply.

In the beginning, most of your time will be spent on familiarizing yourself with how to build widgets, learning the Dart syntax for the different Flutter APIs, and the tooling around the Flutter framework.

Overall, Flutter’s learning curve is only steep in the beginning, but it should reach a plateau once you get the basic concepts down.

Community

Without further explanation, we already know who the winner is, it’s React Native. This is mainly because of two facts:

- React Native entered the scene first. It was initially released in 2015 while Flutter is only released in 2017.

- JavaScript and React developers who want to build mobile apps are naturally drawn to the technology.

Even though this is the case, let’s take a moment to examine how well Flutter is doing compared to React Native when it comes community and overall public interest:

React Native

- GitHub stars: 68k

- GitHub issues: 13.5k

- Stack Overflow: 37k questions

- Discord group: 35k members

- reactnative reddit: 15.6k subscribers

Flutter

- GitHub stars: 36k

- GitHub issues: 12.5k issues

- Stack Overflow: 5k questions

- Gitter: 5k members

- FlutterDev reddit: 5.8k subscribers

With the numbers above, you can really see the difference between Flutter’s community and React Native. That said, those numbers shouldn’t be underestimated as it’s expected to grow as more and more people realizes the potential of Flutter.

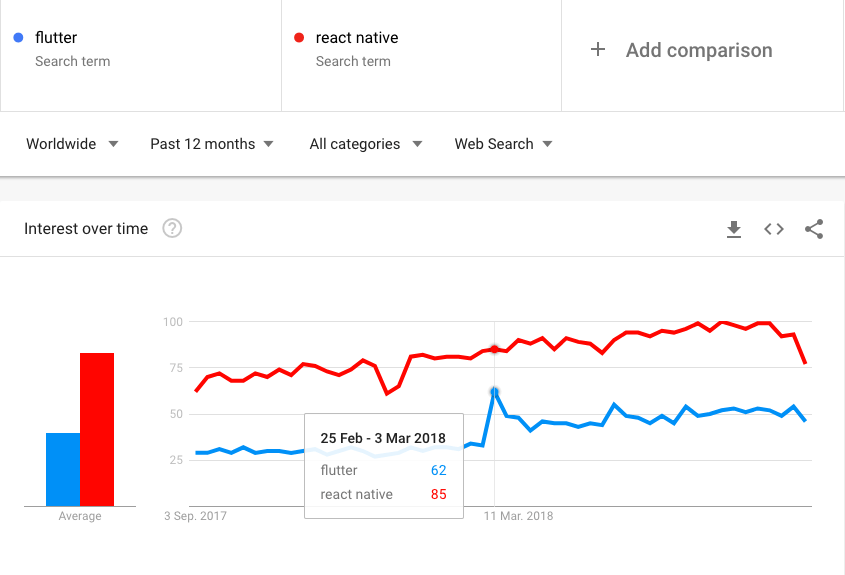

If we go over at Google Trends, we can see that the overall public interest with React Native and Flutter is climbing up at a steady pace in the past 12 months. Flutter peaked at around the first quarter of 2018. This suggests that companies and independent developers worldwide are checking out Flutter as an alternative for their mobile app development needs:

Tooling

The availability of tools that makes the work of a developer easier and more pleasing plays a huge role in their productivity as well. Tooling includes:

- Text-editor and IDE support - code completion, debugger, simulator integration.

- Command-line tools - for checking system requirements, creating a new project, hot reload.

- Libraries and UI kits - for implementing different kinds of functionality like payment processing and social login.

- Third-party services - continuous integration, error reporting.

This is another area where the huge community support in React Native really trumps Flutter.

React Native is supported in popular text-editors like Atom, Sublime Text, WebStorm, Visual Studio Code. While Flutter is only supported in IntelliJ IDEA, Visual Studio Code, and Android Studio.

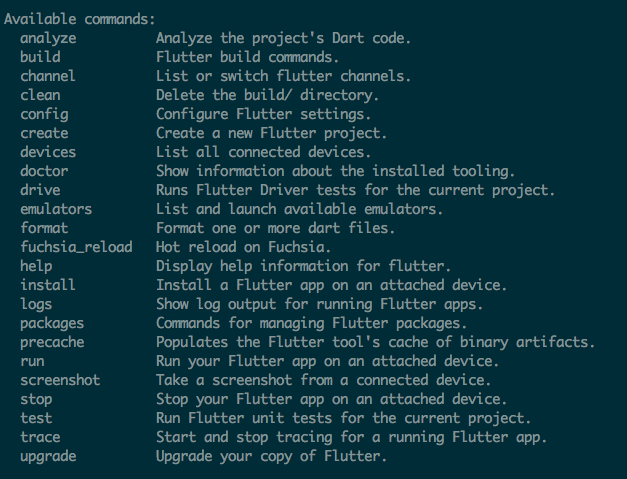

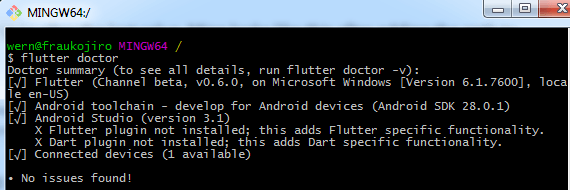

For command-line tools, while Flutter only has its built-in CLI, it comes packed with a lot of features. Some of the most useful ones include doctor which checks if your machine has all the necessary software to build apps with Flutter, create for generating a new Flutter app, install for installing Flutter packages and build for building the app:

This is a far cry from what the React Native CLI offers as it only allows you to generate a new project, link native modules, and run the development server. But even though this is the case, the community compensates by creating tools like the Ignite CLI and Haul.

In terms of libraries, React Native taps into the huge repository of JavaScript packages over at npm. Existing React packages can be easily converted to work with React Native, while libraries that don’t need to access native features can be used immediately (for example, MomentJS).

On the other hand, Flutter taps into the Dart package repository for its third-party library needs. Unlike React Native, these packages will often need to be written from scratch to utilize the Dart syntax as well as work with the APIs exposed by the Flutter SDK.

For third-party services, they usually have a JavaScript client that works with their HTTP API. Again, React Native has the advantage. Services like Sentry, Pusher, and Twilio all have JavaScript clients that work with the web. Making those clients work inside the React Native environment is fairly straightforward.

Overall, the winner in the developer productivity criteria is React Native. The only sub-criteria where Flutter won is the documentation, while React Native took all the rest.

Winner: React Native

User experience

When it comes to User Experience, Flutter has the clear advantage because it’s drawing the UI directly on the native platform’s canvas. As explained earlier in the section on how Flutter works, this is theoretically faster than how React Native works, which is to communicate with the native platform via a “bridge”.

I can’t really present you with hard numbers, but someone has already done the benchmarking before. If you want to know the details, be sure to check out this tutorial: Examining performance differences between Native, Flutter, and React Native mobile development. The results in that tutorial say that React Native uses more CPU while Flutter uses more memory. The difference is only small for both instances, but the app used as an example is a simple one (a stopwatch app). What we don’t know is whether the usage continue to rise at the same rate as the app demands more memory and CPU from the device.

Using those results, I’m not going to give credit to either. CPU and memory usage should be both efficient. But then again, it all depends on the app that you’re building. If your app requires a certain CPU intensive task to finish at the least amount of time then CPU efficiency is the least of your concern, because you need all that juice to complete the task faster. On the other hand, if you expect your users to be running your app along with others, then you should prioritize CPU efficiency instead.

Winner: None

Hardware API support

When it comes to hardware capability support, both React Native and Flutter come with a decent set of hardware APIs out of the box.

Even though React Native doesn’t have support for camera, Bluetooth, and biometrics, developers who need them usually create a native module and upload them on GitHub.

In Flutter, most hardware APIs that are needed for most apps are already included in their built-in collection of APIs. If you need something that isn’t already supported, you can search for it on the Dart packages website. Most likely, someone has already started developing a package for it. But just like in React Native, some packages only support one platform.

Yet again, React Native wins this round because of the sheer number of hardware capabilities being exposed by other developers. Even though some of those have bugs or have poor support, it’s still better than implementing something from scratch.

Winner: React Native

Based on what you’ve read, you already know that React Native is the overall winner. That’s already expected because the criteria in which it won is closely tied to the number of developers using it. React Native came out first, and it has the advantage of the whole JavaScript and React community behind it.

Further reading

If you want to learn more about Flutter, here a few tutorials that can help you understand it further:

- What’s Revolutionary about Flutter

- Why we chose Flutter and how it’s changed our company for the better

- Flutter FAQ

Conclusion

That’s it! In this tutorial, we’ve taken a quick look at Flutter, a promising new mobile app development from Google. You learned some of its pros and cons, and how it compares to React Native.

In my own opinion, even though Flutter isn’t as battle-tested as React Native, I think it’s production-ready. The only downside is the initial developer productivity. React Native’s learning curve isn’t as steep as Flutter, especially for developers who already have experience in JavaScript and React. Furthermore, because of the huge community behind React Native, there are lots of third-party packages already written for integrating with popular services such as Pusher, Auth0, and Realm.

At the end, which framework you choose all depends on whether you can afford to invest more time and resources in learning Flutter or not. Flutter definitely has a lot of potential, and it deserves to be checked out by native and cross-platform developers alike.

Stay tuned for the second part of this tutorial series where we’ll take a look at the basics of creating an app with Flutter!

Getting started with Flutter - Part 2: Creating your first app

This is the second part of a two-part series on getting started with Flutter. You can find part one here. In this part, we’ll be setting up our machine for Flutter development and create a simple app.

Prerequisites

This tutorial assumes no previous knowledge of Flutter. Though you need to have previous programming experience in order to follow along. Specifically, you need to know basic object-oriented programming concepts such as variables, conditionals, loops, classes, and objects.

Knowledge of the Dart language is optional. If you’ve done any sort of programming work previously, the syntax should be easy to pick up.

JavaScript knowledge will be helpful as well, especially ES6 features.

We’ll be setting up the development environment in this tutorial so your machine doesn’t need to have Flutter installed already. This tutorial assumes that you know your way around the operating system you’re using. This means you should know how to add environment variables, and install different pieces of software.

App Overview

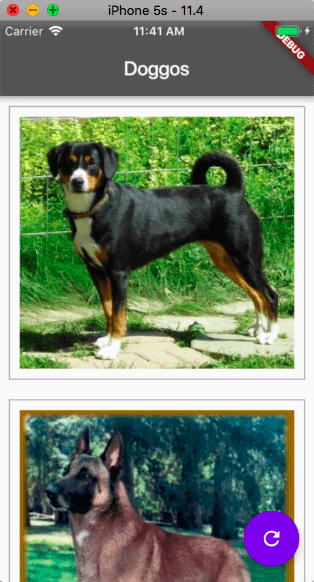

We’re going to build a dog lister app. Here’s what the final output will look like:

As you might already imagine, this app allows the user to view a list of dog photos. They can click on the floating action button to load a new photo which will get appended to the end of the list.

You can find the full source code of the app on this GitHub repo.

Setting up Flutter

In this section, we’ll be setting up Flutter. There are sub-sections for the general setup, Android-specific, and iOS-specific setup. Note that you cannot develop for iOS if you’re on Windows or Linux. If you’re on Mac, you can develop both Android and iOS apps. This tutorial was tested on Windows 7, Ubuntu 16.04, and Mac OS High Sierra. But it should work as well if you’re using any other flavors or versions of those operating systems.

General Setup

These are the steps you need to follow regardless of the operating system you’re using.

- Install Git and set up a user account.

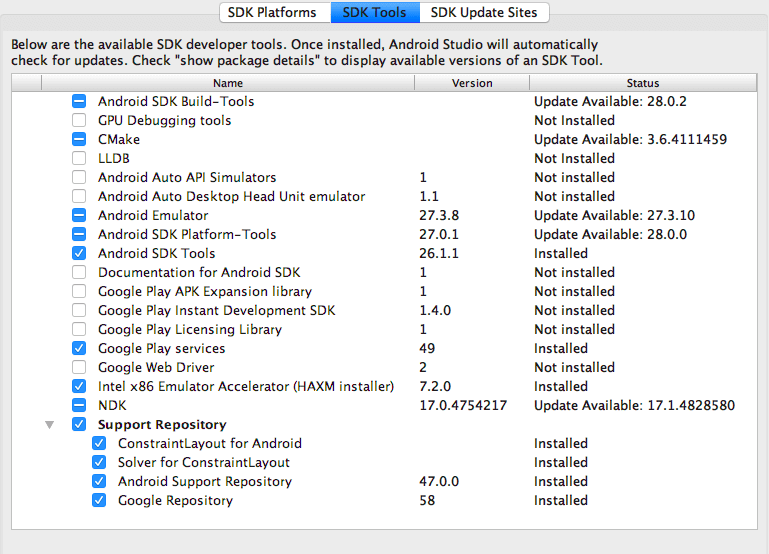

- Install Android Studio. Setting it up should be fairly straightforward. It will also prompt you to install the essential packages so I’m no longer going to go into details. Once installed, make sure the following platforms and SDK tools are installed:

- These are the build tools in text form:

- CMake

- Android Emulator

- Android SDK Platform - Tools

- Android SDK Tools

- Google Play services

- Intel x86 Emulator Accelerator

- NDK

- Support Repository

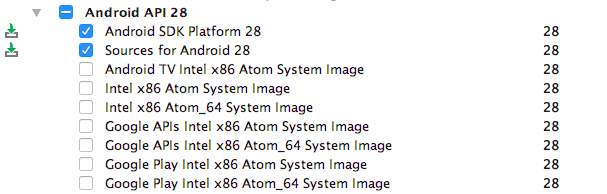

As for the Android platform, the only requirement is the Android SDK Platform 28.

- Install Visual Studio Code. After that, install the Flutter extension. Installing the Flutter extension will install Dart extension as well:

- Download and install Genymotion emulator. You can also use the Android emulator in Android Studio if you want, but we’ll be using Genymotion in this tutorial. As for the virtual device, I had good luck with devices using API 19 and above.

- Flutter will also require the Flutter and Dart plugin for Android Studio, you can install those if you want but we’re not really going to use Android Studio in this tutorial so you can skip it. If you want to use Android Studio then go to Preferences → Plugins then click on Browse Repositories, search for “Flutter” and install it. This will ask you to install Dart as well so just agree.

Mac OS setup

This section shows the steps to follow to setup Flutter on Mac. Mac OS High Sierra version 10.13.6 was used for testing. But it should also work if you have a lower or higher version of High Sierra installed.

General setup

These are the general steps in setting up Flutter on Mac OS.

- Make sure that you have curl, and unzip installed. You can install these via Homebrew if you don’t already have them.

- Download the Flutter SDK from here. At the time of writing this tutorial, the most recent version is 0.6.0. Always stick with the latest available version.

- Extract the zip file using the

unzipcommand or the archive manager that you have on your machine:

unzip ~/Downloads/flutter_macos_v0.6.0-beta.zip

- Copy the

flutterfolder to where you store your development tools. Mine is in the root of my user directory. - Open your bash profile and add Flutter to your path:

nano ~/.bash_profile # open bash profile

export PATH=/Users/$USER/flutter/bin:$PATH # add this with the rest of your exports

- Source your bash profile for the changes to take effect:

source ~/.bash_profile

Android-specific setup

If you want to develop Android apps with Flutter, here are the steps:

- Run

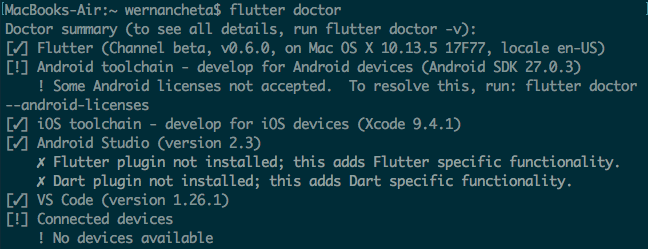

flutter doctorto check what else your system lacks before you can start developing apps in Flutter. Mine looks like this:

- After that, all you need to do is run

flutter doctor --android-licensesand accepting the licenses by responding withyto each of the questions asked.

iOS-specific setup

Follow these steps if you want to develop iOS apps with Flutter.

- If you want to develop iOS apps with Flutter, install the latest stable version of Xcode via the App Store.

- Configure the Xcode command-line tools:

sudo xcode-select --switch /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer

- Accept the license agreement:

sudo xcodebuild -license

Installing on Windows

Follow these steps if you’re using Windows. This was specifically tested on Windows 7 so there’s a high chance that it will work on higher versions of the OS as well.

Android-specific setup

- Download the latest copy of the Flutter SDK from the SDK Archive page for Windows. At the time of writing this tutorial, the latest is version 0.6.0.

- Once downloaded, extract the zip file and copy the resulting

flutterfolder to yourC:drive. After copying, the resulting path should beC:\flutterand there should be aflutter_console.batfile at the root of that directory. - Double-click on the

flutter_console.batfile insideC:\flutter. This should open a new command line window. Runflutter doctorto check which system requirement you’re still lacking to develop Flutter apps. In my case, it required me to accept the licenses for Android by runningflutter doctor --android-licensesand responding withy(yes) to all the licenses. flutter doctorshould also complain about not having a connected device. To solve this, boot up the Genymotion or Android emulator and runflutter doctoragain.- The requirement for the Flutter and Dart plugin for Android Studio is optional because we’re not really going to use Android Studio to write code in this tutorial.

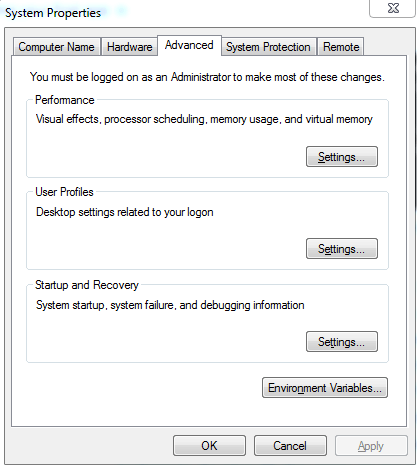

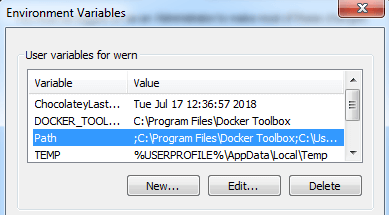

- Go to your advanced system settings. You can find this one either in the Control Panel or right-clicking on Computer and select System properties. Once you see a window similar to the one below, click on Environment Variables:

- Under User Variables, edit the

Pathvariable:

- Append

;C:\flutter\binafter the last value. Mine looks like this after adding the path to Flutter:

;C:\Program Files\Docker Toolbox;C:\Users\wern\AppData\Roaming\npm;C:\Users\wern\AppData\Local\Programs\Microsoft VS Code\bin;C:\flutter\bin

- Save the changes. This will allow you to execute any Flutter command from either the default command line, PowerShell, or Git Bash. I personally prefer Git Bash because its character set doesn’t mess up the check mark and it’s a whole lot more readable than the other two:

Installing on Ubuntu

Follow these steps if you’re on Ubuntu or any Linux distribution. Just execute the equivalent command for your particular flavor of Linux if it’s different. Ubuntu 16.04 LTS is used for testing.

Android-specific setup

- Before anything else, make sure to update the packages installed on your operating system first. You can do so by opening the software updater and installing all the relevant updates. Alternatively, you can also run

sudo apt-get updatefrom the terminal. - Download the latest version of the Flutter SDK from the SDK archives page. At the time of writing this tutorial, the most recent version is 0.6.0.

- Extract the

.tar.xzfile in the root of your home directory. For me, it’s in/home/wern/flutter, where theflutterdirectory is the extracted folder containing aflutter_console.batfile in its root. - Update the

.bash_profilefile to include the path to theflutter/binfolder. Make sure you have the Android paths in there as well:

export ANDROID_HOME=$HOME/Android/Sdk

export PATH=$PATH:$ANDROID_HOME/tools

export PATH=$PATH:$ANDROID_HOME/tools/bin

export PATH=$PATH:$ANDROID_HOME/platform-tools

export PATH=$HOME/flutter/bin:$PATH

- Run

flutter doctorto check your system for software requirements. If you followed the general setup, the only thing left for you to do is executeflutter doctor --android-licensesto accept the Android licenses. Just respond withyto all of those to accept it.

Building the hello world app

Start by generating a new Flutter app:

flutter create doglister

Directory structure

Once the project is created, drag it into VS code. We’re using VS code because it has the most complete Flutter support (Dart syntax, code completion, debugging tools).

By default, you should see the following directory structure:

android- where Android-related files are stored. If you’ve done any sort of cross-platform mobile app development before, this, along with theiosfolder should be pretty familiar.ios- where iOS-related files are stored.lib- this is where you’ll be working on most of the time. By default, it contains amain.dartfile, this is the entry point file of the Flutter app.test- this is where you put the unit testing code for the app. We won’t really be working on it in this tutorial.pubspec.yaml- this file defines the version and build number of your app. It’s also where you define your dependencies. If you’re coming from a web development background, this file has the same job description as thepackage.jsonfile so you can define the external packages (from the Dart packages website) you want to use in here.

Note that I’ve skipped on other folders and files because most of the time you won’t really need to touch them.

Running the app

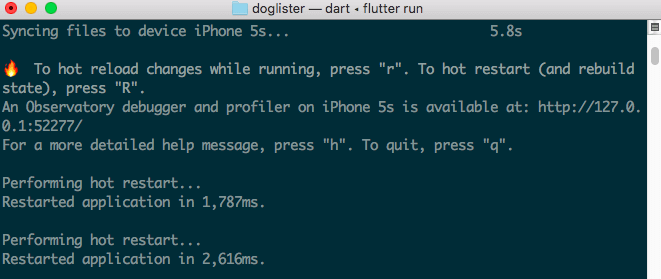

Next, open an iOS simulator or Android emulator and run the app once it has completely booted:

flutter run

The command above detects any running instance of an Android or iOS simulator so it should automatically pick up the one you launched beforehand.

Anytime you make a change to the code and you want to preview the change, simply hit the r key while in the terminal window. This hot reloads the app but the state will still be retained. But if you notice that the change doesn’t appear, you might need to hit the Shift + R key to hot restart the app. Note that this wouldn’t retain the app state like hot reload does.

If you find it cumbersome to be hitting the r key each time you make a change, consider going into debug mode in Visual Studio code. You can do that by going to Debug → Start Debugging, or simply hit Ctrl + Shift + F5 or ⌘ + Shift + F5 on your keyboard. While on debug mode, everytime you hit save, the app is hot reloaded so you don’t have to go back and forth between your text editor, simulator, and the terminal while you’re working.

Hello world app

The code that comes with the Flutter starter app is a bit complicated, so we’ll stick with the same hello world app from this CodeLab first. Open the lib/main.dart file in the project directory and put the following code:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart'; // import the material package

void main() => runApp(MyApp()); // render the MyApp widget

// define a stateless widget

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

@override // override the build method from the StatelessWidget

Widget build(BuildContext context) { // define the method for rendering the app

return MaterialApp(

title: 'Welcome to Flutter', // the title of the app

home: Scaffold( // specify the screen structure

// the app's header

appBar: AppBar( // the widget for rendering an app header

title: Text('Welcome to Flutter'), // the header text

),

// the contents of the body

body: Center( // center the contents

child: Text('Hello World'), // render some text

),

),

);

}

}

To have a better understanding of what’s going on, let’s break down the code above.

First, we import the Material library from Flutter:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

This allows us to use widgets that implement Material Design. Among those are the MaterialApp, Scaffold, and AppBar widgets that we’re using above. The methods that we’re using are either part of a library you’ve imported, or part of the Flutter framework itself.

Note that almost everything in Flutter is a widget, and each one can have its own set of properties and child widgets. So Center and Text are also widgets.

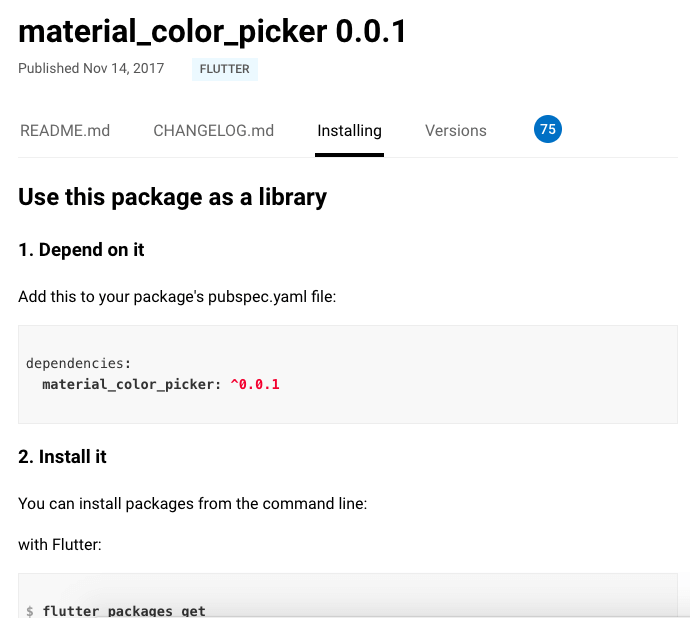

For most packages, you’ll have to search for it on the Dart packages website and add it to your pubspec.yaml file:

But in this case, the library that we’re working with is a part of Flutter. When we create a new app with flutter create, the Flutter library is already installed, and with that, the material library among others is also installed.

Next, we define the main method. If you’ve worked with languages such as Java, this method should look familiar. This is the entry point of the whole program so it must always be defined if you want to render something on the screen:

void main() => runApp(MyApp())

But what about the fat-arrow (=>)? If you’re familiar with ES6 features in JavaScript, this is pretty much the same. It’s just a more concise way of defining functions, so we’re actually running the runApp() function inside the main() function. This function makes the MyApp widget the root of the widget tree. This effectively renders the widget, along with its children into the screen.

In Flutter, there are two types of widget that you’ll commonly work with: stateless and stateful. The difference between the two is that stateless widgets don’t manage it’s own internal state, while a stateful widget does. For example, a button widget doesn’t need to keep track of anything internally while a counter widget needs to keep track of its current count because it needs it for display. In our case, we’re creating a stateless widget because all we need to do is render something on the screen. To create a stateless widget, you need to extend the StatelessWidget class:

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

// ...

}

That class requires you to override its build method which should return the actual contents of the widget. In this case, we’re using the MaterialApp widget as a wrapper. This allows us to easily implement Material Design for the widgets that we’re going to render as its child:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return MaterialApp(

title: 'Welcome to Flutter',

home: Scaffold(

...

),

);

}

Note that the MaterialApp widget doesn’t only allow us to use the Material Design theme, it also handles navigation and navigation animations. So the home property actually allows us to define the widget to render on the home route. For that, we’re using the Scaffold widget which provides the structure for the layout that we’re trying to build.

The Scaffold widget accepts the appBar (app header) and the body (main content of the app):

appBar: AppBar(

title: Text('Welcome to Flutter'),

),

body: Center(

child: Text('Hello World'),

),

Those are the basics of building the UI in Flutter. Basically, everything in Flutter is a widget. There are widgets used for specifying the UI structure (for example, Scaffold). There are also widgets that allow you to render something on the screen (for example, Text). Each widget can have their own child, and those child widgets can also have their own children and so on. The only caveat is that some widgets won’t accept just any child. For example, widgets like the Scaffold only accept a handful of widget types.

If you’re like me and you’re coming from a framework like React Native, then you must be thinking that it’s a whole lot of work! And I agree with you. Building the UI of the app will definitely take longer especially if you’re just starting out. But once you get used to it, you’ll be productive in no time. This is where the documentation really shines because everything you need is literally just one search away.

Building the dog lister app

Now it’s time for us to build the app that we’ve set out to build, the dog lister app. For this, we’ll be using the same Flutter project that we created earlier.

Directory structure

First, let’s talk about the directory structure. We’ll be following the default directory structure set by Flutter, but we’re going to add a few folders inside the lib directory as well:

- `src`

- `models`

- `dog_model.dart`

- `widgets`

- `card_list.dart`

- `app.dart`

- `main.dart`

Go ahead and create those folders and files. Feel free to consult the GitHub repo as a basis.

Entry point file

Open the lib/main.dart file and replace the existing contents with the following:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart'; // import the material library

import 'src/app.dart'; // import the app.dart local file

void main() {

runApp(App());

}

All of these lines should look familiar except for the second line if you haven’t previously worked with relative linking. In the first line, we’re trying to link a Flutter package, thus the package: prefix. But for Dart files that are inside the project directory, all you have to do is specify the path in which they’re stored.

The third to fifth lines is just the long way of doing this:

void main() => runApp(App())

Initializing the main app file

Next, open the lib/src/app.dart file. This is where we will add the main content of the app. Start by importing the Material library:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

Unlike the hello world app from earlier, we will be using a stateful widget for this app. A stateful widget requires a createState() method to be implemented. Inside the method body is where you return the stateful widget:

// lib/src/app.dart

class App extends StatefulWidget {

createState() {

return AppState();

}

}

Next, declare the actual stateful widget. From the name of the method above (createState) which returns this widget, and also the class that the widget below extends (State), it can look like we’re just declaring the state of the stateful widget. But in reality, we’re creating the actual widget, not just its state. It still requires us to declare a build method which returns the contents of the widget, the only difference is that we’re going to add an internal state to this widget later on. For now, we’ll simply return the UI components:

// lib/src/app.dart

class AppState extends State<App> {

Widget build(context) {

return MaterialApp(

home: Scaffold(

body: Container(),

floatingActionButton: FloatingActionButton(

child: Icon(Icons.refresh),

onPressed: () => {

// nothing for now..

},

backgroundColor: Colors.deepPurpleAccent[700],

),

appBar: AppBar(

title: Text('Doggos'),

backgroundColor: Colors.black54,

),

),

);

}

}

In case you’re wondering what this weird-looking syntax means, this means that we want to create a copy of the State class that will work specifically for the App class we created right above this class. And since the App class is extending the StatefulWidget class, this means that we’re inheriting the methods from the StatefulWidget class as well. One of these methods is the setState method which allows us to update the state. You’ll see this in action later on:

class AppState extends State<App> {

// ...

}

The code above should look familiar except for the Container and floatingActionButton widget that we’re using:

Container- used as a wrapper for other widgets for them to occupy the available space in the screen. In this case, we’re not really wrapping anything so it simply acts as a placeholder. If you don’t pass in another widget to aContainer, it won’t actually occupy the screen.FloatingActionButton- this widget is used for creating, you guessed it, a floating action button! In case you’re not familiar, these are the buttons that seemingly hover over the rest of the UI. They’re usually circular in shape and are often used with theIconwidget. TheFloatingActionButtonwidget is special because theScaffoldwidget accepts it as a parameter. As mentioned earlier, not all widgets can accept all other types of widget.

Aside from that, we’re also adding custom colors to the appBar and floatingActionButton widgets. In Flutter, colors are not represented using hex color codes, instead they’re represented in ARGB format. There are also color constants, which can be controlled to be lighter or darker based on the number you specify. Note that the Material theme comes with default colors which are automatically applied to some of the UI elements (for example, appBar and floatingActionButton), so by specifying a color, we’re basically overriding the default color assigned by the theme.

In case you’re wondering why we had to create two separate classes just to implement a stateful widget, this is because of the way widgets work in Flutter. We already know that stateless widgets have this method called build. This method automatically gets called whenever the data that you pass to it gets updated from a parent widget. In effect, this wipes out the current state of that widget. And that’s why it’s called a stateless widget.

On the other hand, we have stateful widgets. As you have seen, they require two separate classes in order to work. This is because the primary widget (in this case, the App class) will also get its current state wiped out if a data that it’s depending on gets updated from its parent widget. So the reason why we’re returning a second class which serves as the widget’s state is so we could keep the current data from being over-written. If you’re familiar with JavaScript closures, stateful widgets work similarly. In the example below, the counter() function is the primary widget class while the function inside is the widget’s state:

function counter(num){

var x = num;

return function(y){

return x = x + y;

}

}

var num = counter(3);

num(4); // outputs: 7

num(3); // outputs: 10

That’s it for now. We’ll come back to this file later once we’ve created the widget for rendering a list of cards.

Dog model

Models in Dart allows us to define a new data type to be used inside our app. This provides structure and uniformity to the different kinds of data that we’re using inside the app. It also serves as a nice tool for documenting what type of data we’re expecting for the properties of an object. This is very useful when working on a collection of objects.

To define a model in Dart, you use the same syntax as for defining a class, only this time you’re not going to need to extend another class. Inside the class, you define the properties. In this case, we only have one property called url. Below that, we declare the constructor which accepts a parsed JSON as its argument. We’re using Map<String, dynamic> to annotate its type. The parsed JSON is basically a JavaScript object so we used the equivalent data type in Dart which is Map. Lastly, <String, dynamic> is the type of the key and value pairs for each object:

// lib/src/models/dog_model.dart

class DogModel {

String url;

DogModel(Map<String, dynamic> parsedJson) {

url = parsedJson['message'];

}

}

But what about the message property we’re accessing from the parsedJson? We’ll be using the Dog API service from Dog.ceo to get the dog pictures, and its response looks something like this:

{

"status": "success",

"message": "https://images.dog.ceo/breeds/shihtzu/n02086240_10785.jpg"

}

The DogModel is extracting that message property to get the image URL. Later on, you’ll see how we’re actually passing the parsedJson to the DogModel.

CardList widget

The CardList widget is used for rendering the cards which shows a dog picture. This is a stateless widget which depends on the data that comes from the lib/src/app.dart file.

Start by importing the Material library and Dog model:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

import '../models/dog_model.dart';

Next, create the widget. Below, we’re using the List class as the data type for the collection of dog images. In Dart, a List is pretty similar to an array, it allows us to add a collection of objects to it. Note that not just any object can be added because we’ve added the DogModel as a constraint, this means that only objects of type DogModel can be added to the list. After that, we set images as the context for the widget. Later on in the lib/src/app.dart file you will see how to pass these images to the widget:

class CardList extends StatelessWidget {

final List<DogModel> images;

CardList(this.images); // set the widget's context

// next: add build method

}

Next, add the build() function. Here we’re checking if there are any images in the list. If there is, then we use the ListView widget to render a list. This requires an itemCount and itemBuilder properties to be passed in. These are the total number of images in the list and the function for rendering each list item.

The context and the item’s index is passed as an argument to the itemBuilder. This allows us to extract a specific index from the list. The context is a handle to the location of a widget in the widget tree. We don’t really have any use for it so I’m not going to expound further.

If no images are available, we simply render a Text widget with some text in it:

Widget build(context) {

if(this.images.length > 0){

return ListView.builder(

itemCount: images.length, // the total number of images

itemBuilder: (context, int index) { // the function for rendering each list item

return buildCard(images[index]);

}

);

}

return Center(child: Text('No doggos for you yet...'));

}

// next: add buildCard widget

Note that unlike JavaScript, we have to explicitly define the condition which returns a boolean value. So we can’t simply do something like this:

if(this.images.length){

// ...

}

Next is the widget for rendering each list item. Each item represents a single instance of the DogModel class. We’re using a Container widget as the main wrapper. This allows us to add a decoration, padding, margin and child widgets:

Widget buildCard(DogModel image) {

return Container(

decoration: BoxDecoration(

border: Border.all(color: Colors.grey),

),

padding: EdgeInsets.all(10.0),

margin: EdgeInsets.all(10.0),

child: Image.network(image.url),

);

}

Most of the properties that the Container widget expects are part of Flutter’s painting library:

decoration- used for painting things like borders, box shadows, and fills on the screen. In this case, we’re using it to surround the container with a grey border on all sides.padding- used for adding an empty space inside the surrounding area of the container.margin- used for adding an empty space outside the surrounding area of the container.

If you’ve worked with CSS before, these concepts should look familiar. The only difference is the syntax that we’re using.

As for the child, we’re rendering an Image widget. The network() method allows us to display an image from the internet, all it requires is the URL that points out to the image resource.

Bringing everything together

Going back to the lib/src/app.dart file, we’re now ready to make use of the CardList widget.

At the top of the file, import the libraries, models, and widgets that we’re going to need:

// lib/src/app.dart

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

// add these:

import 'package:http/http.dart' show get; // for making http requests

import 'models/dog_model.dart'; // dog model

import 'dart:convert'; // for parsing JSON strings

import 'widgets/card_list.dart'; // CardList widget

Note that these libraries come pre-installed when you create a new Flutter project. Some of these are libraries are really big like Dart’s HTTP library. That’s why we’re only extracting the get method from it.

Next, update the AppState class to include the initialization of the two states that we’ll be using:

class AppState extends State<App> {

bool _loaderIsActive = false; // whether the loader is currently showing or not

List<DogModel> images = []; // the list of images

// next: add fetchDog method

}

The fetchDog() function is responsible for updating the state whenever the user taps on the button for loading a new image. When this happens, we want to show a loading animation in the screen. This animation will only be hidden once the HTTP request is done:

void fetchDog() async {

// show the loader

setState(() {

_loaderIsActive = true;

});

// make an HTTP request to get the dog photo

var response = await get('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random');

var dogModel = DogModel(json.decode(response.body));

// hide the lower and add the newly loaded image into the state

setState(() {

_loaderIsActive = false;

images.add(dogModel);

});

}

// next: add build method

In Flutter, the setState() method is used for updating the state of a Stateful widget. Before we request for a new image, we update the state so the loader will show up, then we call it again once the image has been loaded, this time to add the new image to the list and hide the loader.

The fetchDog() function uses the same async/await pattern that we use in JavaScript. The get() function in Dart’s HTTP library returns a Future which is just a fancy term for Promises in JavaScript. This Future represents a potential value which will be available in the future. So by default, the response variable doesn’t actually contain the value that we’re expecting right after we call the get() function. By using the async/await pattern, we make the program wait for this future value to become available before we execute the rest of the code inside the function. Meanwhile, all the codes outside the function will continue to execute.

Next, update the widget’s build method to show the loader when _loaderIsActive is true and show the CardList if it’s false. Then execute the fetchDog() function when the floatingActionButton is pressed:

Widget build(context) {

return MaterialApp(

home: Scaffold(

body: Center(child: _loaderIsActive == true ? CircularProgressIndicator() : CardList(images)), // update this:

floatingActionButton: FloatingActionButton(

child: Icon(Icons.refresh),

onPressed: fetchDog, // update this: use fetchDog instead of the empty function

backgroundColor: Colors.deepPurpleAccent[700],

),

)

);

}

Once that’s done, the app should already be functional. Pressing the button should show the loader, and once the image has been loaded it should be added to the list. If you don’t already have the app running, launch an Android emulator or iOS simulator instance and execute the following command from the root of the project directory:

flutter run

Conclusion

That’s it! In this tutorial, you learned how to create your very first Flutter app. Along the way, you also learned some of the important Flutter concepts like stateful and stateless widgets, how to use Dart packages, how to make HTTP requests and parse JSON strings, and lastly, rendering things on the screen.

That also concludes this series. I hope you gained the necessary knowledge in order to continue exploring Flutter. Flutter is a very young technology, so early adopters are really important for its growth. The more people who use Flutter, the better the technology gets.

You can find the code used in this tutorial on its GitHub repo.

*Originally published by Wern Ancheta at *https://pusher.com

#android #ios #flutter