Project LightSpeed: Rewriting the Messenger codebase for a faster, smaller, and simpler messaging app

- We are excited to begin rolling out the new version of Messenger on iOS. To make the Messenger iOS app faster, smaller, and simpler, we rebuilt the architecture and rewrote the entire codebase, which is an incredibly rare undertaking and involved engineers from across the company.

- Compared with the previous iOS version, this new Messenger is twice as fast to start and is one-fourth the size. We reduced core Messenger code by 84 percent, from more than 1.7M lines to 360,000.

- We accomplished this by using the native OS wherever possible, reusing the UI with dynamic templates powered by SQLite, using SQLite as a universal system, and building a server broker to operate as a universal gateway between Messenger and its server features.

Messenger first became a standalone app in 2011. At that time, our goal was to build the most feature-rich experience possible for our users. Since then, we’ve added payments, camera effects, Stories, GIFs, and even video chat capabilities. But with more than one billion people using Messenger every month, the full-featured messaging app that looked simple on the surface was far more complex behind the scenes. The back end that was required to help us build, test, and manage all those features made the app far more complex. At its peak, the app’s binary size was greater than 130 MB. That and the large amount of code made the app’s cold start much slower, especially on older devices — and with nine different tabs, it was trickier for the people using it to navigate.

In 2018, we redesigned and simplified the interface with the release of Messenger 4. But we wanted to do even more. We looked at how we would build a messaging app today if we were starting from scratch. What had changed since we first began developing Messenger nearly a decade earlier? Quite a lot, it turns out. In fact, the way mobile apps are written has fundamentally changed. Which is why, at F8 last year, we announced our intention to make Messenger’s iOS app faster, smaller, and simpler. We called it Project LightSpeed.

To build this new version of Messenger, we needed to rebuild the architecture from the ground up and rewrite the entire codebase. This rewrite allowed us to make use of significant advancements in the mobile app space since the original app launched in 2011. In addition, we were able to leverage state-of-the-art technology that we’ve developed over the intervening years. Starting today, we are excited to roll out the new version of Messenger on iOS globally over the next few weeks. Compared with the previous iOS version, Messenger is twice as fast to start* and one-fourth the size. With this new iteration, we’ve reimagined how Messenger thinks about building apps and started from the ground up with a new client core and a new server framework. This work has helped us advance our own state-of-the-art technologies and the new codebase is designed to be sustainable and scalable for the next decade, laying the foundation for private messaging and interoperability across apps.

Smaller and faster

We started with the premise that Messenger needed to be a simple, lightweight utility. Some apps are immersive (video streaming, gaming); people spend hours using them. Those apps take up a lot of storage space, battery time, etc., and the trade-off makes sense. But messages are just tiny snippets of text that take less than a second to send. Fundamentally, a messaging app should be one of the smallest, lightest-weight apps on your phone. With that principle in mind, we began looking at the right way to make our iOS app significantly smaller.

A small application downloads, installs, updates, and starts faster for the person using it, regardless of the device type or network conditions. A small app is also easier to manage, update, test, and optimize. When we started thinking about this new version, Messenger’s core codebase had grown to more than 1.7 million lines of code. Editing a few sections of code wasn’t going to be enough.

The simplest way to get a smaller app would have been to strip away many of the features we’ve added over the years, but it was important to us to keep all the most used features, like group video calling. So we stepped back and looked at how we could apply what we’ve learned over the past decade and what we know about the needs of the people on our apps today. After exploring our options, we decided we needed to look past the interface and dig into the infrastructure of the app itself.

Completely rewriting a codebase is an incredibly rare undertaking. In most cases, the enormous effort required to rewrite an app would result in only minimal, if any, real gains in efficiency. But in this case, early prototyping showed that we could realize significant gains, which motivated us to attempt something that’s been done only a few times before with an app of this size. It was no small undertaking. While it was started by a handful of engineers, Project LightSpeed ultimately required more than 100 engineers to complete and deliver the final product.

In the end, we reduced core Messenger code by 84 percent, from more than 1.7M lines to 360,000. We accomplished this by rebuilding our features to fit a simplified architecture and design. While we kept most of the features, we will continue to introduce more features over time. Fewer lines of code makes the app lighter and faster, and a streamlined code base means engineers can innovate more quickly.

Simpler

One of our main goals was to minimize code complexity and eliminate redundancies. We knew a unified architecture would allow for global optimization (instead of having each feature focused on local optimizations) and allow code to be reused in smart ways. To build this unified architecture, we established four principles: Use the OS, reuse the UI, leverage the SQLite database, and push to the server.

Use the OS

Mobile operating systems continue to evolve rapidly and dramatically. New features and innovations are constantly being added due to user demands and competitive pressures. When building a new feature, it’s often tempting to build abstractions on top of the OS to plug a functionality gap, add engineering flexibility, or create cross-platform user experiences. But the existing OS often does much of what’s needed. Actions like rendering, transcoding, threading, and logging can all be handled by the OS. Even when there is a custom solution that might be faster for local metrics, we use the OS to optimize for global metrics.

While UI frameworks can be powerful and increase developer productivity, they require constant upkeep and maintenance to keep up with the ever-changing mobile OS landscape. Rather than reinventing the wheel, we used the UI framework available on the device’s native OS to support a wider variety of application feature needs. This reduced not only size, by avoiding the need to cache/load large custom-built frameworks, but also complexity. The native frameworks don’t have to be translated into sub-frameworks. We also used quite a few of the OS libraries, including the JSON processing library, rather than building and storing our own libraries in the codebase.

Overall, our approach was simple. If the OS did something well, we used it. We leveraged the full capability of the OS without needing to wait for any framework to expose that functionality. If the OS didn’t do something, we would find or write the smallest possible library code to address the specific need — and nothing more. We also embraced platform-dependent UI and associated tooling. For any cross-platform logic, we used an operating extension built in native C code, which is highly portable, efficient, and fast. We use this extension for anything OS-like that’s globally suboptimal, or anything that’s not covered by the OS. For example, all the Facebook-specific networking is done in C on our extension.

Reuse the UI

In Messenger, we had multiple versions of the same UI experience. For example, at the outset of this project, we had more than 40 different contact list screens. Each screen had slight design differences, depending on factors like phone renderings — and each of those different screens had to be enhanced to support features like landscape mode, dark mode, and accessibility, which doubled the number we were supporting. This meant a lot of views, and the views accounted for a large percentage of the size of an app like Messenger. To simplify and remove redundancies, we constrained the design to force the reuse of the same structure for different views. So we needed only a few categories of basic views, and those could be driven by different SQLite tables.

In today’s Messenger, the contact list is a single dynamic template. We are able to change how the screen looks without any extra code. Every time someone loads the screen — to send a message to a group, read a new message, etc. — the app has to talk to the database to load the appropriate names, photos, etc. Instead of having the app store 40 screen designs, the database now holds instructions for how to display different building blocks depending on the various sub-features being loaded. This single contact list screen is extensible to support a large number of features, such as contact management, group creation, user search, messaging security, stories security, sharing, story sharing, and much more. In the iOS world, this is a single view controller that has proper flexibility to support all these needs. Using this more elegant solution across all our designs helped us remove quite a bit of code.

Use SQLite

Most mobile applications use SQLite as a storage database. However, as features grow organically, each ends up with its own unique way of storing, accessing data, and implementing associated business logic. To build our universal system, we took an idea from the desktop world. Rather than managing dozens of independent features and having each pull information and build its own cache on the app, we leveraged the SQLite database as a universal system to support all the features.

Historically, coordinating data sharing across features required the development of custom, complex in-memory data caching and transaction subsystems. Transferring this logic between the database and the UI slowed down the app. We decided to forgo that in favor of simply using SQLite and letting it handle concurrency, caching, and transactions. Now, rather than supporting one system to update which friends are active now, another to update changes in profile pictures in your contact list, and another to retrieve the messages you receive, requests for data from the database are self-contained. All the caching, filtering, transactions, and queries are all done in SQLite. The UI merely reflects the tables in the database.

This keeps the logic simple and functional, and it limits the impact on the rest of the app. But we went even further. We developed a single integrated schema for all features. We extended SQLite with the capability of stored procedures, allowing Messenger feature developers to write portable, database-oriented business logic, and finally, we built a platform (MSYS) to orchestrate all access to the database, including queued changes, deferred or retriable tasks, and for data sync support.

MSYS is a cross-platform library built in C that operates all the primitives we need. Consolidating the code all into one library makes managing everything much easier; the it is more centralized and more focused. We try to do things in a single way — one way to send messages to the server, one way to send media, one way to log, etc. With MSYS, we have a global view. We’re able to prioritize workloads. Say the task to load your message list should be a higher priority than the task to update whether somebody read a message in a thread from a few days ago; we can move the priority task up in the queue. Having a universal system simplifies how we support the app as well. With MSYS, it’s easier to track performance, spot regressions, and fix bugs across all these features at once. In addition, we made this important part of the system exceptionally robust by investing in automated tests, resulting in a (very rare in the industry) 100 percent line code coverage of MSYS logic.

Use the server

For anything that doesn’t fit into one of the categories above, we push it to the server instead. We had to build new server infrastructure to support the presence of MSYS’s single integrated data and sync layer on the client. The original Messenger’s client-server interactions worked like traditional apps do — for each feature, there is an explicit protocol and wire format for the client to sync data and update any changes to the server. The app then has to implement that protocol and coordinate the correct database updates to drive the UI. This means that for each feature in the app, there’s a lot of (ultimately unnecessary) custom platform-specific business logic.

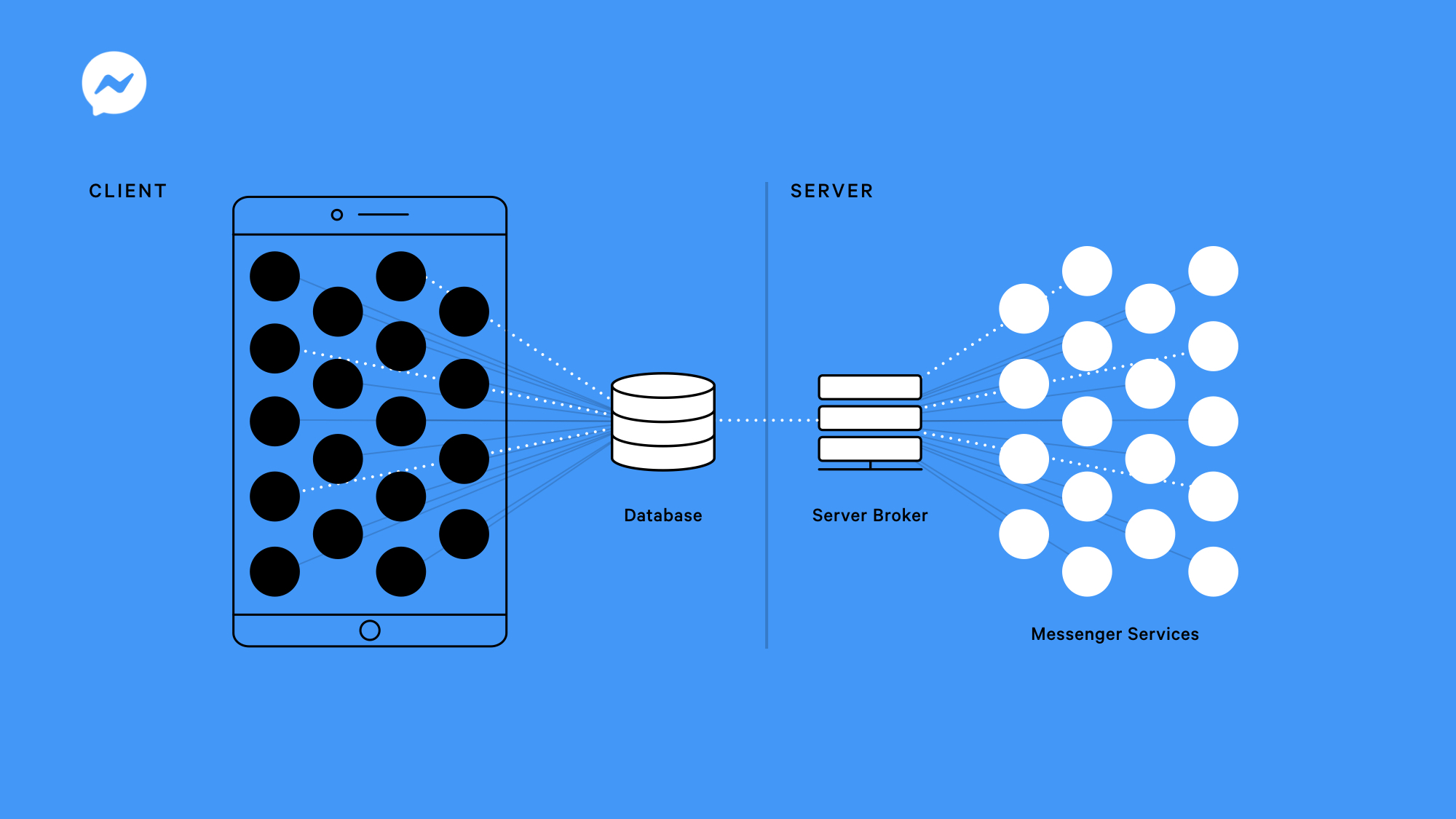

Coordinating logic between client and server is very complex and can be error-prone — even more so as the number of features grows. For example, receiving a text message involves updates to messages tables, updates to the associated thread snippet, updates to last-modified time/bumping the thread, deletion of any optimistic version of the message that might have been inserted (e.g., from notifications), deletion of tasks that were processing the optimistic version of the message, decryption, and many other tasks. These kinds of client-server interactions extend across all features in the app. As a result, the app ends up solving similar problems repeatedly, and the overall app runtime has non-deterministic behavior in terms of how all these events and interactions come together. Over time, our app had become a busy freeway, with cars backed up in both directions.In today’s Messenger, we have a universal flexible sync system that allows the server to define and implement business and sync logic and ensures that all interactions between the client and the server are uniform. Similar to MSYS on the client, we built a server broker to support all these scenarios while the actual server back-end infrastructure supports the features. The server broker acts as a universal gateway between Messenger and all server features, whereas in the past all client features directly communicated with their server counterparts, using a variety of approaches.

Preventing future code growth

Today’s Messenger is significantly lighter — the codebase has shrunk from 1.7M+ lines to 360,000. The app’s binary size is now one-fourth what it was. But before we put that new codebase into production, we had to be confident that it wouldn’t just expand again as fixes and updates and features are added. To do that, we set budgets per feature and tasked our engineers with following the architectural principles above to stick to those budgets. We also built a system that allows us to understand how much binary weight each feature is bringing in. We hold engineers accountable for hitting their budgets as part of feature acceptance criteria. Completing features on time is important, but hitting quality targets (including but not limited to binary size budgets) is even more important.

Building today’s Messenger has been a long journey, and many engineers across the company had some involvement in its development. And yet, for the people using the app, it won’t look or feel much different. It will start faster, but it will continue to be the same great messaging experience that people have come to expect. But this is just the beginning.

The work we’ve put into rebuilding Messenger will allow us to continue to innovate and scale our messaging experiences as we head into the future. In addition to building an app that’s sustainable for the next decade or more, this work has laid the foundation for cross-app messaging across our entire family of apps. It has also built the foundation we’ll need for a privacy-centered messaging experience.

#react-native #reactnative #reactjs #facebook #webdev