How to use Arduino with Python to develop your own projects?

The emergence of Arduino has made electronic application design much more accessible to all developers. In this tutorial, you’ll discover how to use Arduino with Python to develop your own electronic projects.

Microcontrollers have been around for a long time, and they’re used in everything from complex machinery to common household appliances. However, working with them has traditionally been reserved for those with formal technical training, such as technicians and electrical engineers. The emergence of Arduino has made electronic application design much more accessible to all developers. In this tutorial, you’ll discover how to use Arduino with Python to develop your own electronic projects.

You’ll cover the basics of Arduino with Python and learn how to:

- Set up electronic circuits

- Set up the Firmata protocol on Arduino

- Write basic applications for Arduino in Python

- Control analog and digital inputs and outputs

- Integrate Arduino sensors and switches with higher-level apps

- Trigger notifications on your PC and send emails using Arduino

Table of Contents

- The Arduino Platform

- “Hello, World!” With Arduino

- “Hello, World!” With Arduino and Python

- Conclusion

The Arduino Platform

Arduino is an open-source platform composed of hardware and software that allows for the rapid development of interactive electronics projects. The emergence of Arduino drew the attention of professionals from many different industries, contributing to the start of the Maker Movement.

With the growing popularity of the Maker Movement and the concept of the Internet of Things, Arduino has become one of the main platforms for electronic prototyping and the development of MVPs.

Arduino uses its own programming language, which is similar to C++. However, it’s possible to use Arduino with Python or another high-level programming language. In fact, platforms like Arduino work well with Python, especially for applications that require integration with sensors and other physical devices.

All in all, Arduino and Python can facilitate an effective learning environment that encourages developers to get into electronics design. If you already know the basics of Python, then you’ll be able to get started with Arduino by using Python to control it.

The Arduino platform includes both hardware and software products. In this tutorial, you’ll use Arduino hardware and Python software to learn about basic circuits, as well as digital and analog inputs and outputs.

Arduino Hardware

To run the examples, you’ll need to assemble the circuits by hooking up electronic components. You can generally find these items at electronic component stores or in good Arduino starter kits. You’ll need:

- An Arduino Uno or other compatible board

- A standard LED of any color

- A push button

- A 10 KOhm potentiometer

- A 470 Ohm resistor

- A 10 KOhm resistor

- A breadboard

- Jumper wires of various colors and sizes

Let’s take a closer look at a few of these components.

Component 1 is an Arduino Uno or other compatible board. Arduino is a project that includes many boards and modules for different purposes, and Arduino Uno is the most basic among these. It’s also the most used and most documented board of the whole Arduino family, so it’s a great choice for developers who are just getting started with electronics.

Note: Arduino is an open hardware platform, so there are many other vendors who sell compatible boards that could be used to run the examples you see here. In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to use the Arduino Uno.

Components 5 and 6 are resistors. Most resistors are identified by colored stripes according to a color code. In general, the first three colors represent the value of a resistor, while the fourth color represents its tolerance. For a 470 Ohm resistor, the first three colors are yellow, violet, and brown. For a 10 KOhm resistor, the first three colors are brown, black, and orange.

Component 7 is a breadboard, which you use to hook up all the other components and assemble the circuits. While a breadboard is not required, it’s recommended that you get one if you intend to begin working with Arduino.

Arduino Software

In addition to these hardware components, you’ll need to install some software. The platform includes the Arduino IDE, an Integrated Development Environment for programming Arduino devices, among other online tools.

Arduino was designed to allow you to program the boards with little difficulty. In general, you’ll follow these steps:

- Connect the board to your PC

- Install and open the Arduino IDE

- Configure the board settings

- Write the code

- Press a button on the IDE to upload the program to the board

To install the Arduino IDE on your computer, download the appropriate version for your operating system from the Arduino website. Check the documentation for installation instructions:

- If you’re using Windows, then use the Windows installer to ensure you download the necessary drivers for using Arduino on Windows. Check the Arduino documentation for more details.

- If you’re using Linux, then you may have to add your user to some groups in order to use the serial port to program Arduino. This process is described in the Arduino install guide for Linux.

- If you’re using macOS, then you can install Arduino IDE by following the Arduino install guide for OS X.

Note: You’ll be using the Arduino IDE in this tutorial, but Arduino also provides a web editor that will let you program Arduino boards using the browser.

Now that you’ve installed the Arduino IDE and gathered all the necessary components, you’re ready to get started with Arduino! Next, you’ll upload a “Hello, World!” program to your board.

“Hello, World!” With Arduino

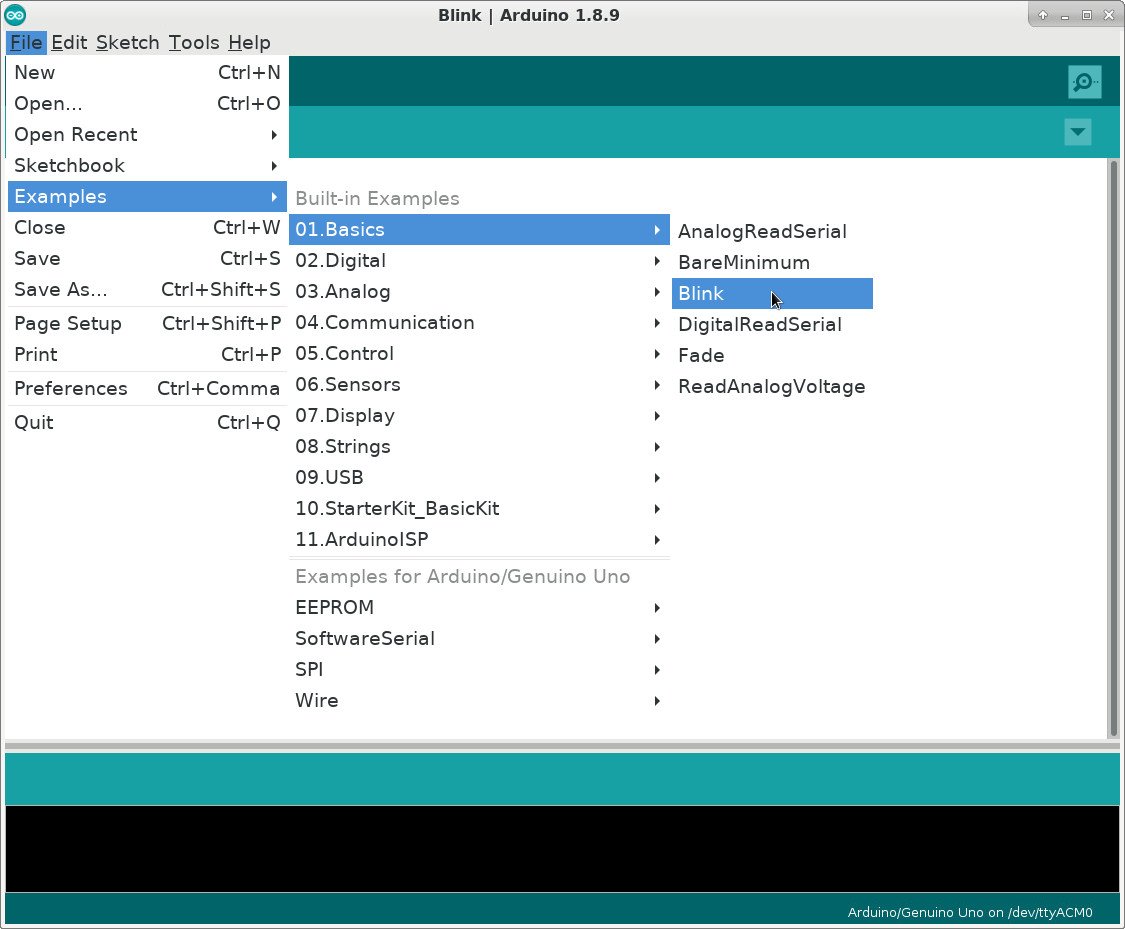

The Arduino IDE comes with several example sketches you can use to learn the basics of Arduino. A sketch is the term you use for a program that you can upload to a board. Since the Arduino Uno doesn’t have an attached display, you’ll need a way to see the physical output from your program. You’ll use the Blink example sketch to make a built-in LED on the Arduino board blink.

Uploading the Blink Example Sketch

To get started, connect the Arduino board to your PC using a USB cable and start the Arduino IDE. To open the Blink example sketch, access the File menu and select Examples, then 01.Basics and, finally, Blink:

The Blink example code will be loaded into a new IDE window. But before you can upload the sketch to the board, you’ll need to configure the IDE by selecting your board and its connected port.

To configure the board, access the Tools menu and then Board. For Arduino Uno, you should select Arduino/Genuino Uno:

After you select the board, you have to set the appropriate port. Access the Tools menu again, and this time select Port:

The names of the ports may be different, depending on your operating system. In Windows, the ports will be named COM4, COM5, or something similar. In macOS or Linux, you may see something like /dev/ttyACM0 or /dev/ttyUSB0. If you have any problems setting the port, then take a look at the Arduino Troubleshooting Page.

After you’ve configured the board and port, you’re all set to upload the sketch to your Arduino. To do that, you just have to press the Upload button in the IDE toolbar:

When you press Upload, the IDE compiles the sketch and uploads it to your board. If you want to check for errors, then you can press Verify before Upload, which will only compile your sketch.

The USB cable provides a serial connection to both upload the program and power the Arduino board. During the upload, you’ll see LEDs flashing on the board. After a few seconds, the uploaded program will run, and you’ll see an LED light blink once every second:

After the upload is finished, the USB cable will continue to power the Arduino board. The program is stored in flash memory on the Arduino microcontroller. You can also use a battery or other external power supply to run the application without a USB cable.

Connecting External Components

In the previous section, you used an LED that was already present on the Arduino board. However, in most practical projects you’ll need to connect external components to the board. To make these connections, Arduino has several pins of different types:

Although these connections are commonly called pins, you can see that they’re not exactly physical pins. Rather, the pins are holes in a socket to which you can connect jumper wires. In the figure above, you can see different groups of pins:

- Orange rectangle: These are 13 digital pins that you can use as inputs or outputs. They’re only meant to work with digital signals, which have 2 different levels:

- Level 0: represented by the voltage 0V

- Level 1: represented by the voltage 5V

- Green rectangle: These are 6 analog pins that you can use as analog inputs. They’re meant to work with an arbitrary voltage between 0V and 5V.

- Blue rectangle: These are 5 power pins. They’re mainly used for powering external components.

To get started using external components, you’ll connect an external LED to run the Blink example sketch. The built-in LED is connected to digital pin #13. So, let’s connect an external LED to that pin and check if it blinks.

Before you connect anything to the Arduino board, it’s good practice to disconnect it from the computer. With the USB cable unplugged, you’ll be able to connect the LED to your board:

Note that the figure shows the board with the digital pins now facing you.

Using a Breadboard

Electronic circuit projects usually involve testing several ideas, with you adding new components and making adjustments as you go. However, it can be tricky to connect components directly, especially if the circuit is large.

To facilitate prototyping, you can use a breadboard to connect the components. This is a device with several holes that are connected in a particular way so that you can easily connect components using jumper wires:

You can see which holes are interconnected by looking at the colored lines. You’ll use the holes on the sides of the breadboard to power the circuit:

- Connect one hole on the red line to the power source.

- Connect one hole on the blue line to the ground.

Then, you can easily connect components to the power source or the ground by simply using the other holes on the red and blue lines. The holes in the middle of the breadboard are connected as indicated by the colors. You’ll use these to make connections between the components of the circuit. These two internal sections are separated by a small depression, over which you can connect integrated circuits (ICs).

You can use a breadboard to assemble the circuit used in the Blink example sketch:

For this circuit, it’s important to note that the LED must be connected according to its polarity or it won’t work. The positive terminal of the LED is called the anode and is generally the longer one. The negative terminal is called the cathode and is shorter. If you’re using a recovered component, then you can also identify the terminals by looking for a flat side on the LED itself. This will indicate the position of the negative terminal.

When you connect an LED to an Arduino pin, you’ll always need a resistor to limit its current and avoid burning out the LED prematurely. Here, you use a 470 Ohm resistor to do this. You can follow the connections and check that the circuit is the same:

- The resistor is connected to digital pin 13 on the Arduino board.

- The LED anode is connected to the other terminal of the resistor.

- The LED cathode is connected to the ground (GND) via the blue line of holes.

For a more detailed explanation, check out How to Use a Breadboard.

After you finish the connection, plug the Arduino back into the PC and re-run the Blink sketch:

As both LEDs are connected to digital pin 13, they blink together when the sketch is running.

“Hello, World!” With Arduino and Python

In the previous section, you uploaded the Blink sketch to your Arduino board. Arduino sketches are written in a language similar to C++ and are compiled and recorded on the flash memory of the microcontroller when you press Upload. While you can use another language to directly program the Arduino microcontroller, it’s not a trivial task!

However, there are some approaches you can take to use Arduino with Python or other languages. One idea is to run the main program on a PC and use the serial connection to communicate with Arduino through the USB cable. The sketch would be responsible for reading the inputs, sending the information to the PC, and getting updates from the PC to update the Arduino outputs.

To control Arduino from the PC, you’d have to design a protocol for the communication between the PC and Arduino. For example, you could consider a protocol with messages like the following:

- VALUE OF PIN 13 IS HIGH: used to tell the PC about the status of digital input pins

- SET PIN 11 LOW: used to tell Arduino to set the states of the output pins

With the protocol defined, you could write an Arduino sketch to send messages to the PC and update the states of the pins according to the protocol. On the PC, you could write a program to control the Arduino through a serial connection, based on the protocol you’ve designed. For this, you can use whatever language and libraries you prefer, such as Python and the PySerial library.

Fortunately, there are standard protocols to do all this! Firmata is one of them. This protocol establishes a serial communication format that allows you to read digital and analog inputs, as well as send information to digital and analog outputs.

The Arduino IDE includes ready-made sketches that will drive Arduino through Python with the Firmata protocol. On the PC side, there are implementations of the protocol in several languages, including Python. To get started with Firmata, let’s use it to implement a “Hello, World!” program.

Uploading the Firmata Sketch

Before you write your Python program to drive Arduino, you have to upload the Firmata sketch so that you can use that protocol to control the board. The sketch is available in the Arduino IDE’s built-in examples. To open it, access the File menu, then Examples, followed by Firmata, and finally StandardFirmata:

The sketch will be loaded into a new IDE window. To upload it to the Arduino, you can follow the same steps you did before:

- Plug the USB cable into the PC.

- Select the appropriate board and port on the IDE.

- Press Upload.

After the upload is finished, you won’t notice any activity on the Arduino. To control it, you still need a program that can communicate with the board through the serial connection. To work with the Firmata protocol in Python, you’ll need the pyFirmata package, which you can install with pip:

$ pip install pyfirmata

After the installation finishes, you can run an equivalent Blink application using Python and Firmata:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

while True:

board.digital[13].write(1)

time.sleep(1)

board.digital[13].write(0)

time.sleep(1)

Here’s how this program works. You import pyfirmata and use it to establish a serial connection with the Arduino board, which is represented by the board object in line 4. You also configure the port in this line by passing an argument to pyfirmata.Arduino(). You can use the Arduino IDE to find the port.

board.digital is a list whose elements represent the digital pins of the Arduino. These elements have the methods read() and write(), which will read and write the state of the pins. Like most embedded device programs, this program mainly consists of an infinite loop:

- In line 7, digital pin 13 is turned on, which turns the LED on for one second.

- In line 9, this pin is turned off, which turns the LED off for one second.

Now that you know the basics of how to control an Arduino with Python, let’s go through some applications to interact with its inputs and outputs.

Reading Digital Inputs

Digital inputs can have only two possible values. In a circuit, each of these values is represented by a different voltage. The table below shows the digital input representation for a standard Arduino Uno board:

To control the LED, you’ll use a push button to send digital input values to the Arduino. The button should send 0V to the board when it’s released and 5V to the board when it’s pressed. The figure below shows how to connect the button to the Arduino board:

You may notice that the LED is connected to the Arduino on digital pin 13, just like before. Digital pin 10 is used as a digital input. To connect the push button, you have to use the 10 KOhm resistor, which acts as a pull down in this circuit. A pull down resistor ensures that the digital input gets 0V when the button is released.

When you release the button, you open the connection between the two wires on the button. Since there’s no current flowing through the resistor, pin 10 just connects to the ground (GND). The digital input gets 0V, which represents the 0 (or low) state. When you press the button, you apply 5V to both the resistor and the digital input. A current flows through the resistor and the digital input gets 5V, which represents the 1 (or high) state.

You can use a breadboard to assemble the above circuit as well:

Now that you’ve assembled the circuit, you have to run a program on the PC to control it using Firmata. This program will turn on the LED, based on the state of the push button:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

board.digital[10].mode = pyfirmata.INPUT

while True:

sw = board.digital[10].read()

if sw is True:

board.digital[13].write(1)

else:

board.digital[13].write(0)

time.sleep(0.1)

Let’s walk through this program:

- Lines 1 and 2 import

pyfirmataandtime. - Line 4 uses

pyfirmata.Arduino()to set the connection with the Arduino board. - Line 6 assigns an iterator that will be used to read the status of the inputs of the circuit.

- Line 7 starts the iterator, which keeps a loop running in parallel with your main code. The loop executes

board.iterate()to update the input values obtained from the Arduino board. - Line 9 sets pin 10 as a digital input with

pyfirmata.INPUT. This is necessary since the default configuration is to use digital pins as outputs. - Line 11 starts an infinite

whileloop. This loop reads the status of the input pin, stores it insw, and uses this value to turn the LED on or off by changing the value of pin 13. - Line 17 waits 0.1 seconds between iterations of the

whileloop. This isn’t strictly necessary, but it’s a nice trick to avoid overloading the CPU, which reaches 100% load when there isn’t a wait command in the loop.

pyfirmata also offers a more compact syntax to work with input and output pins. This may be a good option for when you’re working with several pins. You can rewrite the previous program to have more compact syntax:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

digital_input = board.get_pin('d:10:i')

led = board.get_pin('d:13:o')

while True:

sw = digital_input.read()

if sw is True:

led.write(1)

else:

led.write(0)

time.sleep(0.1)

In this version, you use board.get_pin() to create two objects. digital_input represents the digital input state, and led represents the LED state. When you run this method, you have to pass a string argument composed of three elements separated by colons:

- The type of the pin (

afor analog ordfor digital) - The number of the pin

- The mode of the pin (

ifor input orofor output)

Since digital_input is a digital input using pin 10, you pass the argument 'd:10:i'. The LED state is set to a digital output using pin 13, so the led argument is 'd:13:o'.

When you use board.get_pin(), there’s no need to explicitly set up pin 10 as an input like you did before with pyfirmata.INPUT. After the pins are set, you can access the status of a digital input pin using read(), and set the status of a digital output pin with write().

Digital inputs are widely used in electronics projects. Several sensors provide digital signals, like presence or door sensors, that can be used as inputs to your circuits. However, there are some cases where you’ll need to measure analog values, such as distance or physical quantities. In the next section, you’ll see how to read analog inputs using Arduino with Python.

Reading Analog Inputs

In contrast to digital inputs, which can only be on or off, analog inputs are used to read values in some range. On the Arduino Uno, the voltage to an analog input ranges from 0V to 5V. Appropriate sensors are used to measure physical quantities, such as distances. These sensors are responsible for encoding these physical quantities in the proper voltage range so they can be read by the Arduino.

To read an analog voltage, the Arduino uses an analog-to-digital converter (ADC), which converts the input voltage to a digital number with a fixed number of bits. This determines the resolution of the conversion. The Arduino Uno uses a 10-bit ADC and can determine 1024 different voltage levels.

The voltage range for an analog input is encoded to numbers ranging from 0 to 1023. When 0V is applied, the Arduino encodes it to the number 0. When 5V is applied, the encoded number is 1023. All intermediate voltage values are proportionally encoded.

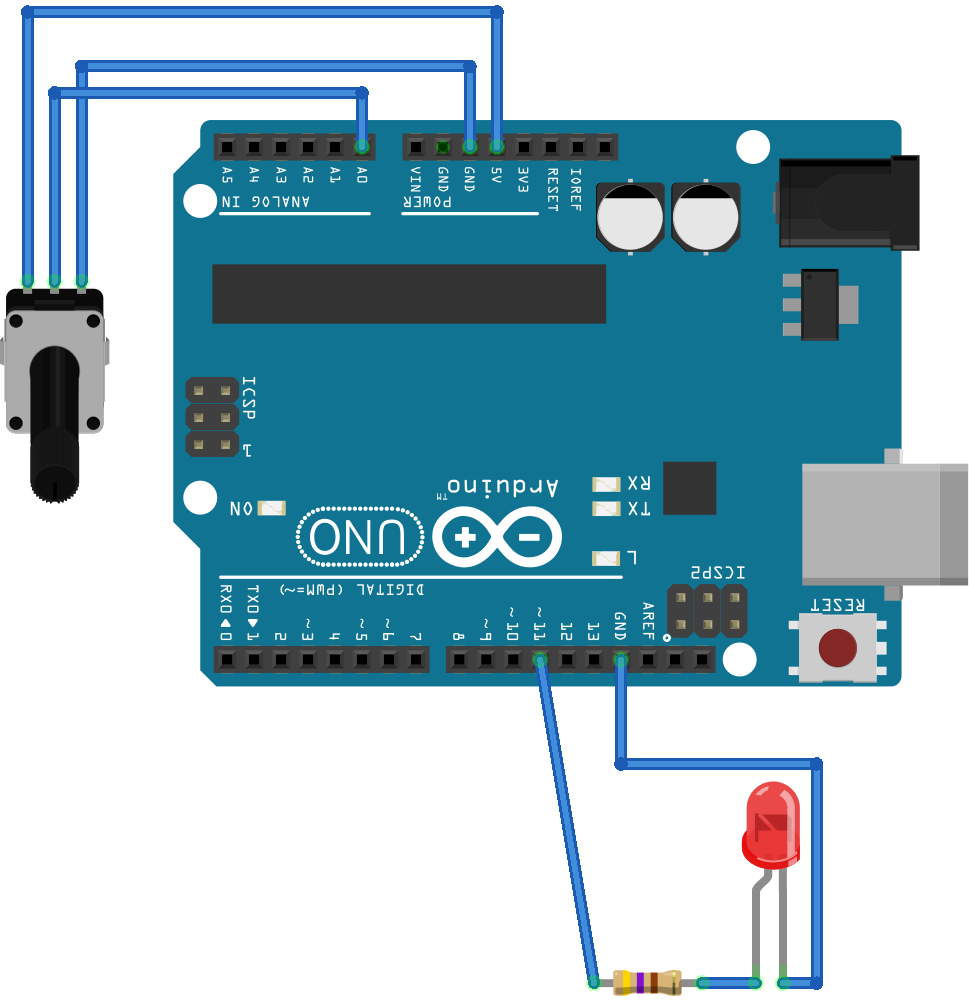

A potentiometer is a variable resistor that you can use to set the voltage applied to an Arduino analog input. You’ll connect it to an analog input to control the frequency of a blinking LED:

In this circuit, the LED is set up just as before. The end terminals of the potentiometer are connected to ground (GND) and 5V pins. This way, the central terminal (the cursor) can have any voltage in the 0V to 5V range depending on its position, which is connected to the Arduino on analog pin A0.

Using a breadboard, you can assemble this circuit as follows:

Before you control the LED, you can use the circuit to check the different values the Arduino reads, based on the position of the potentiometer. To do this, run the following program on your PC:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

analog_input = board.get_pin('a:0:i')

while True:

analog_value = analog_input.read()

print(analog_value)

time.sleep(0.1)

In line 8, you set up analog_input as the analog A0 input pin with the argument 'a:0:i'. Inside the infinite while loop, you read this value, store it in analog_value, and display the output to the console with print(). When you move the potentiometer while the program runs, you should output similar to this:

0.0

0.0293

0.1056

0.1838

0.2717

0.3705

0.4428

0.5064

0.5797

0.6315

0.6764

0.7243

0.7859

0.8446

0.9042

0.9677

1.0

1.0

The printed values change, ranging from 0 when the position of the potentiometer is on one end to 1 when it’s on the other end. Note that these are float values, which may require conversion depending on the application.

To change the frequency of the blinking LED, you can use the analog_value to control how long the LED will be kept on or off:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

analog_input = board.get_pin('a:0:i')

led = board.get_pin('d:13:o')

while True:

analog_value = analog_input.read()

if analog_value is not None:

delay = analog_value + 0.01

led.write(1)

time.sleep(delay)

led.write(0)

time.sleep(delay)

else:

time.sleep(0.1)

Here, you calculate delay as analog_value + 0.01 to avoid having delay equal to zero. Otherwise, it’s common to get an analog_value of None during the first few iterations. To avoid getting an error when running the program, you use a conditional in line 13 to test whether analog_value is None. Then you control the period of the blinking LED.

Try running the program and changing the position of the potentiometer. You’ll notice the frequency of the blinking LED changes:

By now, you’ve seen how to use digital inputs, digital outputs, and analog inputs on your circuits. In the next section, you’ll see how to use analog outputs.

Using Analog Outputs

In some cases, it’s necessary to have an analog output to drive a device that requires an analog signal. Arduino doesn’t include a real analog output, one where the voltage could be set to any value in a certain range. However, Arduino does include several Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) outputs.

PWM is a modulation technique in which a digital output is used to generate a signal with variable power. To do this, it uses a digital signal of constant frequency, in which the duty cycle is changed according to the desired power. The duty cycle represents the fraction of the period in which the signal is set to high.

Not all Arduino digital pins can be used as PWM outputs. The ones that can be are identified by a tilde (~):

Several devices are designed to be driven by PWM signals, including some motors. It’s even possible to obtain a real analog signal from the PWM signal if you use analog filters. In the previous example, you used a digital output to turn an LED light on or off. In this section, you’ll use PWM to control the brightness of an LED, according to the value of an analog input given by a potentiometer.

When a PWM signal is applied to an LED, its brightness varies according to the duty cycle of the PWM signal. You’re going to use the following circuit:

This circuit is identical to the one used in the previous section to test the analog input, except for one difference. Since it’s not possible to use PWM with pin 13, the digital output pin used for the LED is pin 11.

You can use a breadboard to assemble the circuit as follows:

With the circuit assembled, you can control the LED using PWM with the following program:

import pyfirmata

import time

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

analog_input = board.get_pin('a:0:i')

led = board.get_pin('d:11:p')

while True:

analog_value = analog_input.read()

if analog_value is not None:

led.write(analog_value)

time.sleep(0.1)

There are a few differences from the programs you’ve used previously:

- In line 10, you set

ledto PWM mode by passing the argument'd:11:p'. - In line 15, you call

led.write()withanalog_valueas an argument. This is a value between 0 and 1, read from the analog input.

Here you can see the LED behavior when the potentiometer is moved:

To show the changes in the duty cycle, an oscilloscope is plugged into pin 11. When the potentiometer is in its zero position, you can see the LED is turned off, as pin 11 has 0V on its output. As you turn the potentiometer, the LED gets brighter as the PWM duty cycle increases. When you turn the potentiometer all the way, the duty cycle reaches 100%. The LED is turned on continuously at maximum brightness.

With this example, you’ve covered the basics of using an Arduino and its digital and analog inputs and outputs. In the next section, you’ll see an application for using Arduino with Python to drive events on the PC.

Using a Sensor to Trigger a Notification

Firmata is a nice way to get started with Arduino with Python, but the need for a PC or other device to run the application can be costly, and this approach may not be practical in some cases. However, when it’s necessary to collect data and send it to a PC using external sensors, Arduino and Firmata make a good combination.

In this section, you’ll use a push button connected to your Arduino to mimic a digital sensor and trigger a notification on your machine. For a more practical application, you can think of the push button as a door sensor that will trigger an alarm notification, for example.

To display the notification on the PC, you’re going to use Tkinter, the standard Python GUI toolkit. This will show a message box when you press the button. For an in-depth intro to Tkinter, check out the library’s documentation.

You’ll need to assemble the same circuit that you used in the digital input example:

After you assemble the circuit, use the following program to trigger the notifications:

import pyfirmata

import time

import tkinter

from tkinter import messagebox

root = tkinter.Tk()

root.withdraw()

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

digital_input = board.get_pin('d:10:i')

led = board.get_pin('d:13:o')

while True:

sw = digital_input.read()

if sw is True:

led.write(1)

messagebox.showinfo("Notification", "Button was pressed")

root.update()

led.write(0)

time.sleep(0.1)

This program is similar to the one used in the digital input example, with a few changes:

- Lines 3 and 4 import libraries needed to set up Tkinter.

- Line 6 creates Tkinter’s main window.

- Line 7 tells Tkinter not to show the main window on the screen. For this example, you only need to see the message box.

- Line 17 starts the

whileloop:- When you press the button, the LED will turn on and

messagebox.showinfo()displays a message box. - The loop pauses until the user presses OK. This way, the LED remains on as long as the message is on the screen.

- After the user presses OK,

root.update()clears the message box from the screen and the LED is turned off.

- When you press the button, the LED will turn on and

To extend the notification example, you could even use the push button to send an email when pressed:

import pyfirmata

import time

import smtplib

import ssl

def send_email():

port = 465 # For SSL

smtp_server = "smtp.gmail.com"

sender_email = "<your email address>"

receiver_email = "<destination email address>"

password = "<password>"

message = """Subject: Arduino Notification\n The switch was turned on."""

context = ssl.create_default_context()

with smtplib.SMTP_SSL(smtp_server, port, context=context) as server:

print("Sending email")

server.login(sender_email, password)

server.sendmail(sender_email, receiver_email, message)

board = pyfirmata.Arduino('/dev/ttyACM0')

it = pyfirmata.util.Iterator(board)

it.start()

digital_input = board.get_pin('d:10:i')

while True:

sw = digital_input.read()

if sw is True:

send_email()

time.sleep(0.1)

You can learn more about send_email() in Sending Emails With Python. Here, you configure the function with email server credentials, which will be used to send the email.

With these example applications, you’ve seen how to use Firmata to interact with more complex Python applications. Firmata lets you use any sensor attached to the Arduino to obtain data for your application. Then you can process the data and make decisions within the main application. You can even use Firmata to send data to Arduino outputs, controlling switches or PWM devices.

If you’re interested in using Firmata to interact with more complex applications, then try out some of these projects:

- A temperature monitor to alert you when the temperature gets too high or low

- An analog light sensor that can sense when a light bulb is burned out

- A water sensor that can automatically turn on the sprinklers when the ground is too dry

Conclusion

Microcontroller platforms are on the rise, thanks to the growing popularity of the Maker Movement and the Internet of Things. Platforms like Arduino are receiving a lot of attention in particular, as they allow developers just like you to use their skills and dive into electronic projects.

You learned how to:

- Develop applications with Arduino and Python

- Use the Firmata protocol

- Control analog and digital inputs and outputs

- Integrate sensors with higher-level Python applications

You also saw how Firmata may be a very interesting alternative for projects that demand a PC and depend on sensor data. Plus, it’s an easy way to get started with Arduino if you already know Python!

#python