Imagine this client email hits your inbox:

“I read that it’s a best practice to feature a company’s brand name in text ads. Should we include our brand name in all of our ad copy?”

Because you already have performance data on your text ad variations, you get to work on crunching the numbers:

“Yes,” you respond.

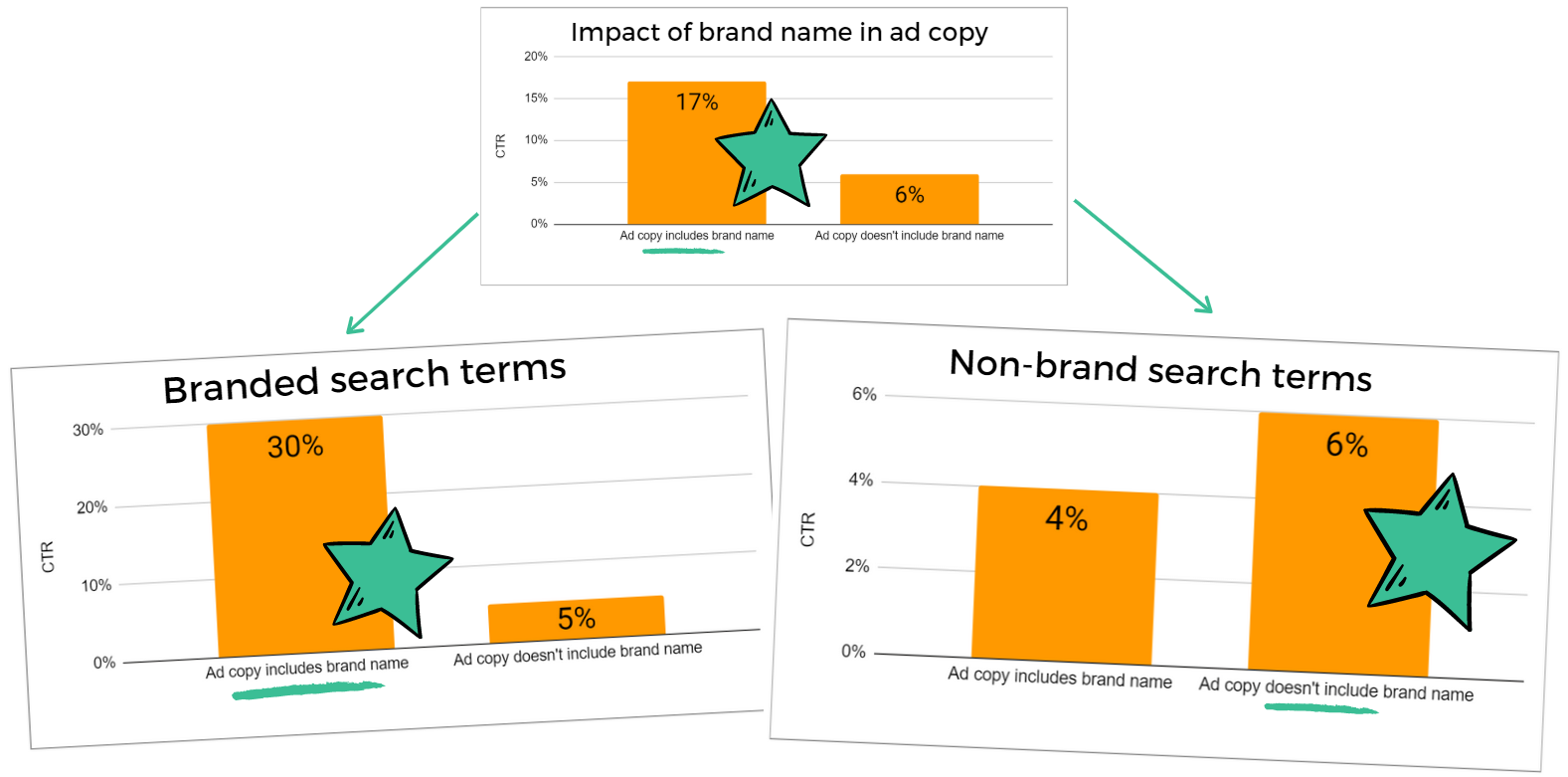

“Ads that mention the brand are nearly 3x more likely to get clicked! I’ll swap in new branded text ads by the end of the week.”

Five minutes go by, when your client replies:

“Interesting. And I assume you’ve controlled for whether the brand is a search keyword?”

“Well…”

Flustered, you crunch the numbers again, this time taking into account whether the search queries were branded.

Your new conclusion contradicts the one you just provided.

“For search queries that don’t include the brand, ads without the brand name are actually 50% more likely to get clicked.”

“For search queries that don’t include the brand, ads without the brand name are actually 50% more likely to get clicked.”

What Happened Here?

You pride yourself in being a data-driven, quantitative marketer.

But now you have to explain to your client why your analysis was wrong until they double-checked your process.

So what caused the error?

We could say that marketers wear many hats and can make mistakes when rushed.

#marketing analytics #paid search #data analytic