JavaScript Basics Before You Learn React

Learn the essential JavaScript basics you need to know before you learn React. This article covers variables, functions, objects, arrays, and more.

If you already have some experience with JavaScript, all you need to learn before React is just the JavaScript features you will actually use to develop React application. Things about JavaScript you should be comfortable with before learning React are:

- ES6 classes

- The new variable declaration let/const

- Arrow functions

- Destructuring assignment

- Map and filter

- ES6 module system

It’s the 20% of JavaScript features that you will use 80% of the time, so in this tutorial I will help you learn them all.

📘 15+ Best JavaScript Books for Beginners and Experienced Coders

Exploring Create React App

The usual case of starting to learn React is to run the create-react-app package, which sets up everything you need to run React. Then after the process is finished, opening src/app.js will present us with the only React class in the whole app:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import logo from './logo.svg';

import './App.css';

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div className=“App”>

<header className=“App-header”>

<img src={logo} className=“App-logo” alt=“logo” />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<a

className=“App-link”

href=“https://reactjs.org”

target=“_blank”

rel=“noopener noreferrer”

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

If you never learned ES6 before, you’d think that this class statement is a feature of React. It’s actually a new feature of ES6, and that’s why learning ES6 properly would enable you to understand React code better. We’ll start with ES6 classes.

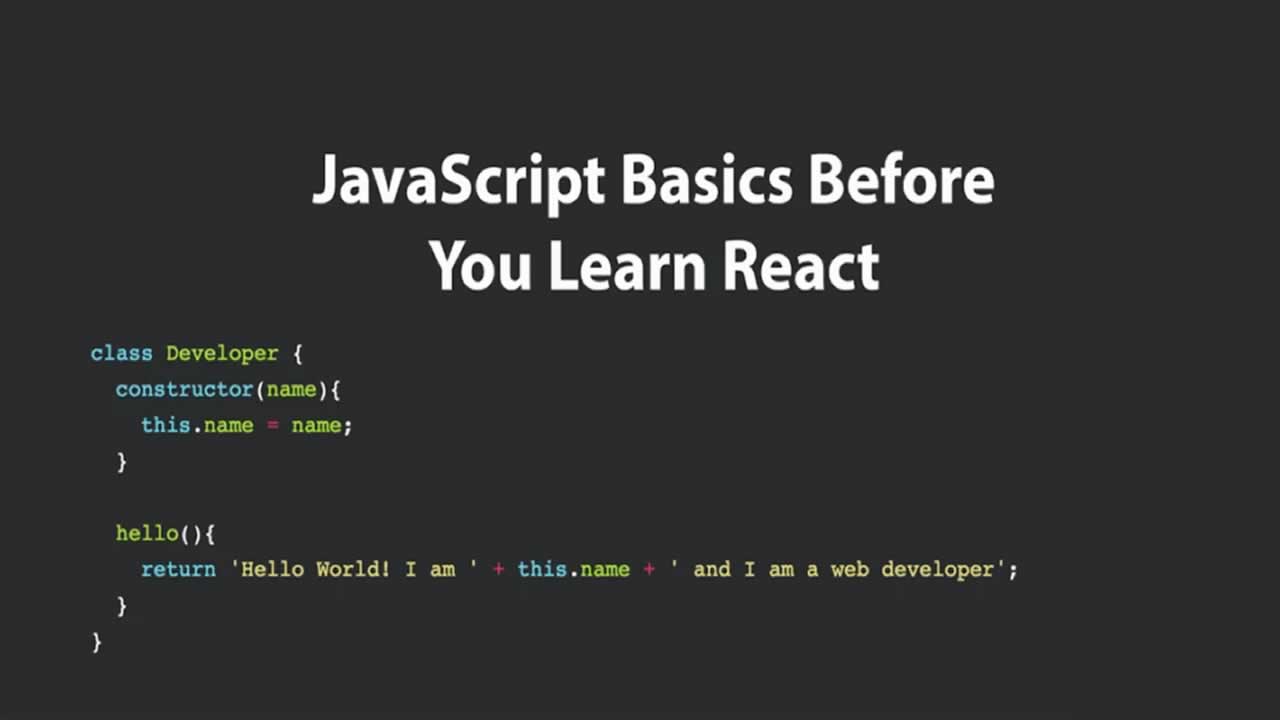

ES6 Classes

ES6 introduced class syntax that is used in similar ways to OO language like Java or Python. A basic class in ES6 would look like this:

class Developer {

constructor(name){

this.name = name;

}

hello(){

return ‘Hello World! I am ’ + this.name + ’ and I am a web developer’;

}

}

class syntax is followed by an identifier (or simply name) that can be used to create new objects. The constructor method is always called in object initialization. Any parameters passed into the object will be passed into the new object. For example:

var nathan = new Developer(‘Nathan’);

nathan.hello(); // Hello World! I am Nathan and I am a web developerA class can define as many methods as the requirements needed, and in this case, we have the hello method which returns a string.

Class inheritance

A class can extends the definition of another class, and a new object initialized from that class will have all the methods of both classes.

class ReactDeveloper extends Developer {

installReact(){

return ‘installing React … Done.’;

}

}

var nathan = new ReactDeveloper(‘Nathan’);

nathan.hello(); // Hello World! I am Nathan and I am a web developer

nathan.installReact(); // installing React … Done.

The class that extends another class is usually called child class or sub class, and the class that is being extended is called parent class or super class. A child class can also override the methods defined in parent class, meaning it will replace the method definition with the new method defined. For example, let’s override the hello function:

class ReactDeveloper extends Developer {

installReact(){

return ‘installing React … Done.’;

}

hello(){

return ‘Hello World! I am ’ + this.name + ’ and I am a REACT developer’;

}

}

var nathan = new ReactDeveloper(‘Nathan’);

nathan.hello(); // Hello World! I am Nathan and I am a REACT developer

There you go. The hello method from Developer class has been overridden.

Use in React

Now that we understand ES6 class and inheritance, we can understand the React class defined in src/app.js. This is a React component, but it’s actually just a normal ES6 class which inherits the definition of React Component class, which is imported from the React package.

import React, { Component } from ‘react’;

class App extends Component {

// class content

render(){

return (

<h1>Hello React!</h1>

)

}

}

This is what enables us to use the render() method, JSX, this.state, other methods. All of this definitions are inside the Component class. But as we will see later, class is not the only way to define React Component. If you don’t need state and other lifecycle methods, you can use a function instead.

Declaring variables with ES6 let and const

Because JavaScript var keyword declares variable globally, two new variable declarations were introduced in ES6 to solve the issue, namely let and const. They are all the same, in which they are used to declare variables. The difference is that const cannot change its value after declaration, while let can. Both declarations are local, meaning if you declare let inside a function scope, you can’t call it outside of the function.

const name = “David”;

let age = 28;

var occupation = “Software Engineer”;Which one to use?

The rule of thumb is that declare variable using const by default. Later when you wrote the application, you’ll realize that the value of const need to change. That’s the time you should refactor const into let. Hopefully it will make you get used to the new keywords, and you’ll start to recognize the pattern in your application where you need to use const or let.

When do we use it in React?

Everytime we need variables. Consider the following example:

import React, { Component } from ‘react’;

class App extends Component {

// class content

render(){

const greeting = ‘Welcome to React’;

return (

<h1>{greeting}</h1>

)

}

}

Since greeting won’t change in the entire application lifecycle, we define it using const here.

The arrow function

Arrow function is a new ES6 feature that’s been used almost widely in modern codebases because it keeps the code concise and readable. This feature allows us to write functions using shorter syntax

// regular function

const testFunction = function() {

// content…

}

// arrow function

const testFunction = () => {

// content…

}

If you’re an experienced JS developer, moving from the regular function syntax to arrow syntax might be uncomfortable at first. When I was learning about arrow function, I used this simple 2 steps to rewrite my functions:

- remove function keyword

- add the fat arrow symbol => after ()

the parentheses are still used for passing parameters, and if you only have one parameter, you can omit the parentheses.

const testFunction = (firstName, lastName) => {

return firstName+’ '+lastName;

}

const singleParam = firstName => {

return firstName;

}

Implicit return

If your arrow function is only one line, you can return values without having to use the return keyword and the curly brackets {}

const testFunction = () => ‘hello there.’;

testFunction();

Use in React

Another way to create React component is to use arrow function. React take arrow function:

const HelloWorld = (props) => {

return <h1>{props.hello}</h1>;

}as equivalent to an ES6 class component

class HelloWorld extends Component {

render() {

return (

<h1>{props.hello}</h1>;

);

}

}Using arrow function in your React application makes the code more concise. But it will also remove the use of state from your component. This type of component is known as stateless functional component. You’ll find that name in many React tutorials.

Destructuring assignment for arrays and objects

One of the most useful new syntax introduced in ES6, destructuring assignment is simply copying a part of object or array and put them into named variables. A quick example:

const developer = {

firstName: ‘Nathan’,

lastName: ‘Sebhastian’,

developer: true,

age: 25,

}

//destructure developer object

const { firstName, lastName } = developer;

console.log(firstName); // returns ‘Nathan’

console.log(lastName); // returns ‘Sebhastian’

console.log(developer); // returns the object

As you can see, we assigned firstName and lastName from developer object into new variable firstName and lastName. Now what if you want to put firstName into a new variable called name?

const { firstName:name } = developer;

console.log(name); // returns ‘Nathan’Destructuring also works on arrays, only it uses index instead of object keys:

const numbers = [1,2,3,4,5];

const [one, two] = numbers; // one = 1, two = 2You can skip some index from destructuring by passing it with ,:

const [one, two, , four] = numbers; // one = 1, two = 2, four = 4Use in React

Mostly used in destructuring state in methods, for example:

reactFunction = () => {

const { name, email } = this.state;

};Or in functional stateless component, consider the example from previous chapter:

const HelloWorld = (props) => {

return <h1>{props.hello}</h1>;

}

We can simply destructure the parameter immediately:

const HelloWorld = ({ hello }) => {

return <h1>{hello}</h1>;

}Map and filter

Although this tutorial focuses on ES6, JavaScript array map and filter methods need to be mentioned since they are probably one of the most used ES5 features when building React application. Particularly on processing data.

These two methods are much more used in processing data. For example, imagine a fetch from API result returns an array of JSON data:

const users = [

{ name: ‘Nathan’, age: 25 },

{ name: ‘Jack’, age: 30 },

{ name: ‘Joe’, age: 28 },

];Then we can render a list of items in React as follows:

import React, { Component } from ‘react’;

class App extends Component {

// class content

render(){

const users = [

{ name: ‘Nathan’, age: 25 },

{ name: ‘Jack’, age: 30 },

{ name: ‘Joe’, age: 28 },

];

return (

<ul>

{users

.map(user => <li>{user.name}</li>)

}

</ul>

)

}

}

We can also filter the data in the render.

<ul>

{users

.filter(user => user.age > 26)

.map(user => <li>{user.name}</li>)

}

</ul>ES6 module system

The ES6 module system enables JavaScript to import and export files. Let’s see the src/app.js code again in order to explain this.

import React, { Component } from ‘react’;

import logo from ‘./logo.svg’;

import ‘./App.css’;

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div className=“App”>

<header className=“App-header”>

<img src={logo} className=“App-logo” alt=“logo” />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<a

className=“App-link”

href=“https://reactjs.org”

target=“_blank”

rel=“noopener noreferrer”

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

Up at the first line of code we see the import statement:

import React, { Component } from ‘react’;and at the last line we see the export default statement:

export default App;To understand these statements, let’s discuss about modules syntax first.

A module is simply a JavaScript file that exports one or more values (can be objects, functions or variables) using the export keyword. First, create a new file named util.js in the src directory

touch util.js

Then write a function inside it. This is a default export

export default function times(x) {

return x * x;

}

or multiple named exports

export function times(x) {

return x * x;

}

export function plusTwo(number) {

return number + 2;

}

Then we can import it from src/App.js

import { times, plusTwo } from ‘./util.js’;

console.log(times(2));

console.log(plusTwo(3));

You can have multiple named exports per module but only one default export. A default export can be imported without using the curly braces and corresponding exported function name:

// in util.js

export default function times(x) {

return x * x;

}

// in app.js

import k from ‘./util.js’;

console.log(k(4)); // returns 16

But for named exports, you must import using curly braces and the exact name. Alternatively, imports can use alias to avoid having the same name for two different imports:

// in util.js

export function times(x) {

return x * x;

}

export function plusTwo(number) {

return number + 2;

}

// in app.js

import { times as multiplication, plusTwo as plus2 } from ‘./util.js’;

Import from absolute name like:

import React from ‘react’;Will make JavaScript check on node_modules for the corresponding package name. So if you’re importing a local file, don’t forget to use the right path.

Use in React

Obviously we’ve seen this in the src/App.js file, and then in index.js file where the exported App component is being rendered. Let’s ignore the serviceWorker part for now.

//index.js file

import React from ‘react’;

import ReactDOM from ‘react-dom’;

import ‘./index.css’;

import App from ‘./App’;

import * as serviceWorker from ‘./serviceWorker’;

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById(‘root’));

// If you want your app to work offline and load faster, you can change

// unregister() to register() below. Note this comes with some pitfalls.

// Learn more about service workers: http://bit.ly/CRA-PWA

serviceWorker.unregister();

Notice how App is imported from ./App directory and the .js extension has been omitted. We can leave out file extension only when importing JavaScript files, but we have to include it on other files, such as .css. We also import another node module react-dom, which enables us to render React component into HTML element.

As for PWA, it’s a feature to make React application works offline, but since it’s disabled by default, there’s no need to learn it in the beginning. It’s better to learn PWA after you’re confident enough building React user interfaces.

Conclusion

The great thing about React is that it doesn’t add any foreign abstraction layer on top of JavaScript as other web frameworks. That’s why React becomes very popular with JS developers. It simply uses the best of JavaScript to make building user interfaces easier and maintainable. There really is more of JavaScript than React specifix syntax inside a React application, so once you understand JavaScript better — particularly ES6 — you can write React application with confident. But it doesn’t mean you have to master everything about JavaScript to start writing React app. Go and write one now, and as opportunities come your way, you will be a better developer.

Thanks for reading and I hope you learned some new things :

#javascript #reactjs